Complemented by detailed preoperative and intraoperative imaging, Dr. Anthony K. Frempong-Boadu’s vast surgical expertise guides the spinal resection of a complex vascular lesion.

Photo: NYU Langone Staff

When a 62-year-old patient with a history of thoracic myelopathy presented with progressive sensory and motor decline despite previous treatment for a complex vascular lesion, a surgical team with vast endovascular and spinal expertise successfully executed a challenging resection that both relieved the patient’s symptoms and restored her function—and quality of life.

A Closer Look at an Intractable Vascular Lesion

Treatment at another institution for the patient’s previously diagnosed spinal arteriovenous malformation ultimately proved unsuccessful. This was likely due to a mischaracterization in diagnosing the complex lesion, combined with the added complexities of extensive vascular disease and previous spinal surgeries. The patient’s accelerating decline, with increasing loss of function in her legs, bladder, and bowel, prompted her referral to Anthony K. Frempong-Boadu, MD, associate professor in the Departments of Neurosurgery and Orthopedic Surgery, for reassessment.

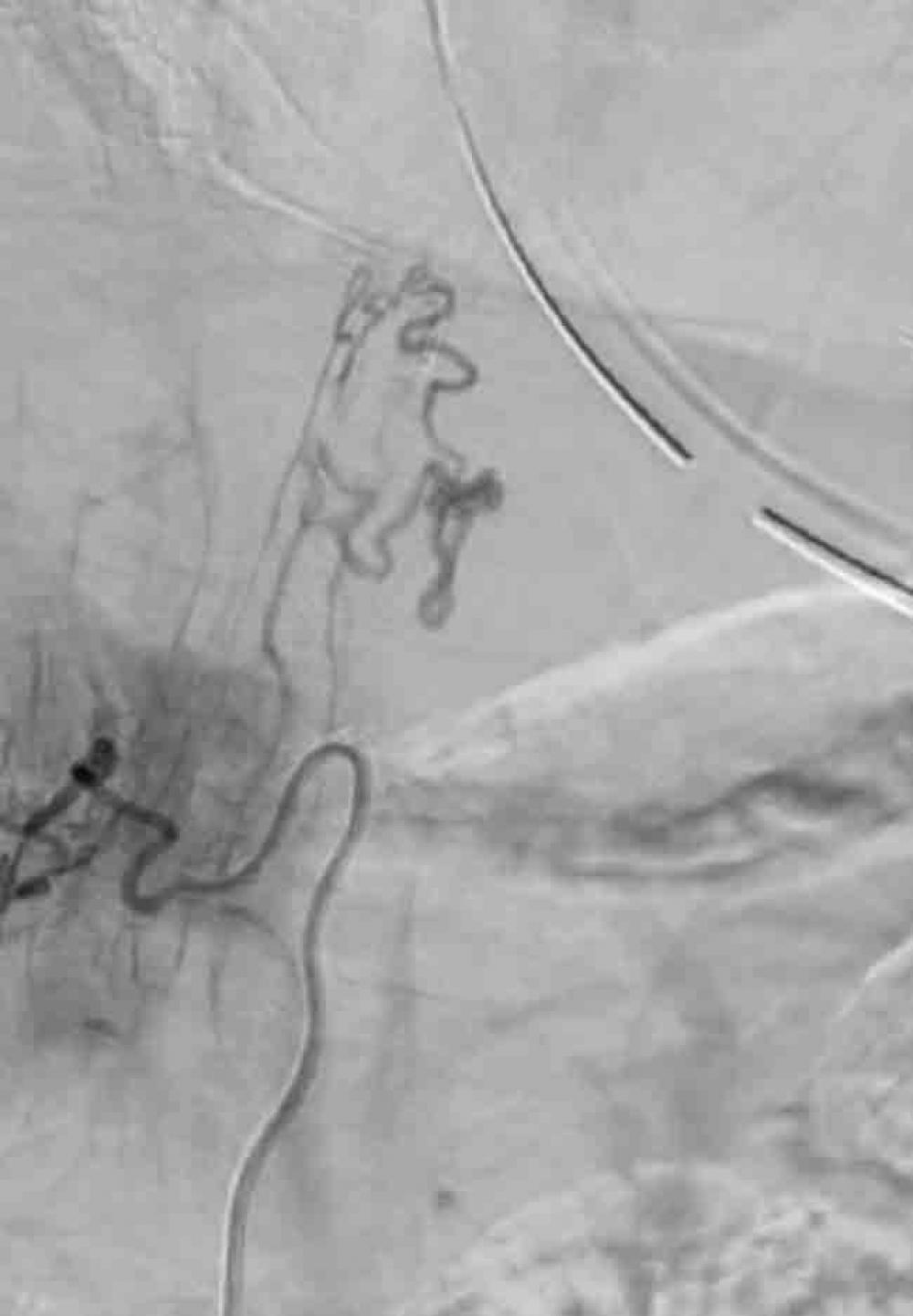

A repeat MRI revealed extensive thoracic cord expansion and edema with enlarged spinal cord surface veins and flow voids from the T6 level down to the conus medullaris. “The appearance of this lesion mimicked a dural fistula, which is typically associated with cord venous congestion,” explains Dr. Frempong-Boadu. However, a subsequent microcatheter-enabled angiogram performed by the neuroendovascular team and Erez Nossek, MD, associate professor in the Department of Neurosurgery, demonstrated the presence of a pial, not a dural, fistula—supplied by both the posterior spinal artery and the anterior spinal artery. “Usually a pial fistula is drained by regional radicular veins into the epidural space, but we believe this patient’s drainage mechanism had shut down, resulting in cord venous congestion over time,” Dr. Frempong-Boadu says.

This nuance in diagnosis explained the other institution’s attempts to embolize the lesion, as a dural fistula involves a more basic abnormal connection between arteries and veins. For true arteriovenous malformation cases such as this, in which the malformed connection also feeds the main vessel to the spine, greater precision via a more extensive surgical resection is needed to achieve the desired outcomes.

Vascular Rearchitecture Requires Essential Expertise

In documented cases, Dr. Frempong-Boadu likens himself to a plumber brought in to rearchitect the highly complex vascular structure surrounding the spine through surgical resection. “A robust artery connected to a vein is like a water main connecting directly to a sewer in an apartment building,” he notes. “Either the veins burst, causing paralysis, or they arterialize, becoming more robust and stealing from the apartment building—the spinal cord—and I need to come in and physically disconnect them.”

The complexities of such a diagnosis warrant a collaborative approach shepherded by a multidisciplinary team of hyperspecialized experts. In this approach, Dr. Frempong-Boadu’s focused spinal cord expertise is complemented by the neurovascular expertise of Dr. Nossek, enabling them to co-navigate the vascular anatomy and find the fistula point for resection.

“In addition to our neurosurgical expertise, finely tuned subspecialty training allows us to subdivide our expertise across the neurological system,” says Dr. Frempong-Boadu. “By limiting our practice to focused parts of the anatomy, we each operate within the bounds of our training, thus ending up with both a vascular and spinal neurosurgeon on the same case.”

Advanced Imaging Techniques Underpin Systematic Surgical Planning

With further endovascular procedures ruled out due to the lesion’s morphology, a multidisciplinary team of neurosurgeons, vascular surgeons, neurointerventional radiologists, and endovascular specialists architected a carefully planned resection. The lesion’s delicate location near the spinal cord demanded a minimal approach to preserve function, aided by a combination of surgical expertise and a suite of high-fidelity endovascular imaging technologies. During surgery, an intraoperative angiogram was achieved via a technically challenging radial artery approach, entering via the wrist and navigating the complex path to the lesion via the aorta, in order to achieve uninterrupted precision in the context of the patient’s extensive vascular disease.

“The standard angiogram, via the groin, is made difficult during spinal surgery when we need to turn the patient to achieve surgical access,” says Dr. Nossek. “Entering through the wrist requires greater technical agility since you have to first direct the catheter toward the head before entering the spinal cord, but it was necessary given this patient’s vascular risk.”

Careful Resection Encompasses Systematic Approach

In this case, with the intraoperative angiogram prepared, Dr. Frempong-Boadu began the surgical approach by performing a posterior T9 to T11 laminectomy and then opening the dura, careful to avoid the surrounding vasculature. Under high-resolution magnification, the engorged vein and feeders of the fistula were visible, along with the proximal venous pouch just distal to the fistula, bulging superficially from the spinal cord. “We bring in a microscope, and align the microscope image and the endovascular image until we have a near overlay before we begin the dissection,” notes Dr. Frempong-Boadu.

With the pial dissection technique, the arteriovenous fistula was carefully dissected and the feeders clipped. The main feeder was coagulated and separated, dissected slowly through the arteriovenous fistula and its main drainage, and detached from the spinal cord. “The dissection has to proceed in the correct order, with the inflow targeted before the outflow,” explains Dr. Frempong-Boadu. “Otherwise, returning to the plumbing analogy, if you take out a pipe and there’s still water coming in, the whole thing explodes when you cut the drain.”

With continuous somatosensory evoked potential and periodical motor evoked potential monitoring stable, the resection and dissection continued to reach the recipient arterialized fistula vein. Indocyanine green (ICG) video angiography was performed, and there were no signs of fistulation or early vein drainage, so the clips were removed. A complete occlusion of the pial arteriovenous fistula was observed, and a previously engorged secondary draining vein appeared bluish in color. An intraoperative angiogram was performed via radial access, showing complete occlusion with no residual shunt.

An Excellent Outcome, Achieved Collectively

Postsurgical recovery, notes Dr. Frempong-Boadu, can vary based on the extent of each patient’s condition and spinal cord involvement. This patient’s initial symptoms were relieved, and with bilateral improvement of weakness in her legs, she is now fully mobile without the need for assistive devices, continuing to achieve progress with ongoing rehabilitation.

That outcome, he adds, is the result of a carefully calibrated approach enabled through meticulous planning by a multidisciplinary team representing complementary surgical expertise. “Guided by real-time imaging and the expertise across an array of specialists, we are able to approach these cases tactically—almost militarily,” concludes Dr. Frempong-Boadu. “Preserving and restoring function, safely, is our absolute priority as we approach these complex cases with an eye toward continually higher-quality outcomes.”