The Team That Performed NYU Langone’s First Split Liver Transplant

Susana Casio and Cooper Cota celebrate the split liver transplant that saved both of their lives, and Cooper's third birthday, with members of their expert care team, including Dr. Adam Griesemer and Dr. Karim J. Halazun.

PHOTO: NYU LANGONE STAFF

It’s 2:45AM on the Saturday of Labor Day weekend. Adam Griesemer, MD, surgical director of the Pediatric Liver Disease and Transplant Program at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone, is home asleep when his phone rings.

On the line is a representative from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Organ Center. There’s a liver available, and it’s a blood match for one of Dr. Griesemer’s patients.

There’s only one problem: the liver is from an adult. Dr. Griesemer’s patient, Cooper Cota, is only 2 years old.

“One of the biggest problems for kids who need a liver transplant is finding a donor liver that’s the right size,” says Dr. Griesemer, who is also an associate professor in the Department of Surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

But of all the body’s organs, the liver is particularly unique in that it regenerates, meaning that when it’s split in two, both parts regrow. Could this one liver actually save two lives?

Cooper’s pediatric hepatologist, Nadia Ovchinsky, MD, director of the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology in the Department of Pediatrics, confirms that the liver is a perfect match for Cooper, whose liver failure was caused by Alagille syndrome, a potentially deadly inherited condition.

A plan is set: about 20 percent of the donor liver can go to Cooper, with the rest going to an adult. “Transplantation is advanced enough that we can offer the littlest children this lifesaving option,” says Dr. Ovchinsky.

An Eligible Adult Is Found

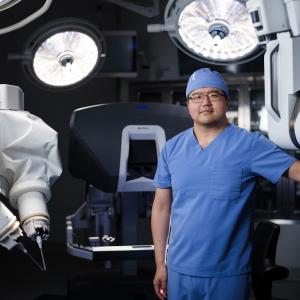

Dr. Griesemer reaches out to his colleague, Karim J. Halazun, MD, surgical director of the Liver Transplant Program. Does he have a patient who could share this donor liver?

Dr. Halazun knows an excellent candidate: 63-year-old Susana Casio, who has fatty liver disease and has been coming to NYU Langone’s Tisch Hospital every few weeks due to complications.

“In addition to having a compatible blood type, Ms. Casio is small enough for the transplant to fit and can tolerate surgery,” says Dr. Halazun, who is also section chief of hepatobiliary surgery in the Division of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, and a professor in the Department of Surgery.

Readying the Patients

A split liver transplant requires three operating rooms running at once: one to divide the liver, one for the pediatric transplant, and one for the adult transplant. Dr. Griesemer enlists Christie Long, RN, assistant nurse manager of transplant and hepatobiliary surgery in the main operating room at NYU Langone’s Kimmel Pavilion, to manage the logistics.

“While these simultaneous procedures present some planning and staffing challenges, our extremely skilled team is prepared for the task,” says Long. “Showing up in moments like these are what make our transplant team so special.” She assists in coordinating all three rooms while mobilizing the necessary operating room staff to ensure each procedure runs smoothly.

In addition to surgeons and anesthesiologists, it takes extremely skilled nurses and operating room technicians to maintain safety and sterility while caring for the patients. Ultimately, more than 20 providers make the surgeries possible.

That Saturday afternoon, Cooper and his family arrive at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital. Casio checks in at Kimmel Pavilion. Both patients are deemed ready for surgery.

Procuring the Donor Liver

While preparations are ongoing at Kimmel Pavilion, transplant surgeon Bonnie E. Lonze, MD, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Surgery and vice chair of research at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, is heading to Teterboro Airport, in New Jersey. She is flying to the city where the donor liver is located.

At 10:00PM, her flight touches down and she heads straight to the local hospital. Her job is to work with a team of transplant surgeons to remove the liver, as well as other organs being donated, and then prepare the liver for transport back to New York City.

Dr. Lonze removes the liver, carefully preserving the blood vessels and bile ducts. “Operative technique is crucial because you have to bring back a perfect organ,” she says. Dr. Lonze leaves the hospital with the donor liver and heads to the airport a little before 2:00AM Sunday. “The clock’s ticking at this point,” she says. “To be viable, the liver needs to be transplanted within four to eight hours, and we need time to split the organ.”

After landing back at Teterboro, Dr. Lonze quickly returns to Kimmel Pavilion. “A special SUV with lights and sirens takes us back to the hospital. We don’t stop for red lights.”

The Liver Is Split

When Dr. Lonze arrives, she heads to the operating room to hand off the donor liver to Dr. Griesemer, and to act as a second pair of hands during the liver split surgery.

“The hardest part of this procedure is ensuring that you don’t injure any of the blood vessels or bile ducts as you split the liver,” says Dr. Griesemer. He prepares one section of liver for Cooper’s transplant, while his colleague Jeffrey M. Stern, MD, assistant professor in the Department of Surgery, prepares the adult portion of the liver. The sections are preserved in a special ice bath solution.

The Transplant Surgeries Begin

While Dr. Griesemer carefully splits the liver in two, Cooper and Casio are prepared for their respective transplant surgeries. This reduces the amount of time the donor liver needs to stay cold.

At 6:15AM on Sunday, Alejandro Torres-Hernandez, MD, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Surgery, starts Cooper’s surgery by making the first incision.

Shortly after, Dr. Griesemer moves to Cooper’s operating room to remove the damaged liver. He and the surgical team place the donor liver in Cooper’s abdomen and connect the donor liver’s blood vessels with Cooper’s to start blood flowing to the transplant.

The surgical team performs a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, a procedure to ensure the proper drainage of bile, a digestive fluid, from the new liver. Dr. Griesemer takes a portion of the small intestine and constructs a new pathway for bile to flow from the new liver to the small intestine. The new liver will grow with Cooper as he grows. Surgery takes about eight hours.

At the same time, Dr. Halazun starts Casio’s procedure and carefully removes her liver. He sews in the adult portion of the donor liver, connecting it to her blood vessels and bile duct. Blood circulates through the transplanted organ. Eleven hours later, surgery is complete.

Recovery and a Special Birthday Meetup

Both Casio and Cooper stay in an intensive care unit and are closely monitored until they are well enough to move to a regular recovery room. After doctors ensure that Cooper’s new liver is functioning properly, he leaves the hospital for home on September 11, about a week after the surgery. Two days later, Casio returns home.

Five months later, she meets Cooper and his family for the first time at NYU Langone to help celebrate his third birthday, along with some members of the transplant team. “It’s so special for our operating room team because we often don’t get to see patients after they’ve received a transplant,” says Long, the assistant nurse manager. “Susana looked amazing, and Cooper was enjoying his third birthday with a huge smile on his face, just like every little 3-year-old should.”

Read and watch more about Cooper and Casio in People and NBCNews.com.