Our Survival Rate for Patients Placed on Prolonged Life Support to Aid Lung Recovery Was Among the Highest in the United States: Here’s Why

Dr. Anthony S. Lubinsky, medical director of respiratory care at NYU Langone, is among the medical intensivists who evaluated patients with COVID-19 for ECMO life support. “They needed to be sick enough that ECMO would make a difference, but not so sick that they were going to die from secondary infections, bleeding, clotting, or other problems,” Dr. Lubinsky says.

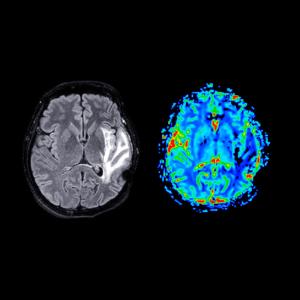

Photo: Jonathan Kozowyk

ECMO doesn’t work well for supporting patients with COVID-19.”

That was the broad consensus within the medical community about venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, a form of prolonged life support in which blood flows through tubing to a machine that adds oxygen and removes carbon dioxide when a patient’s lungs are too impaired to perform these functions. The skepticism was understandable, given the dismal results of studies in the early days of the pandemic. One pooled analysis showed that 16 of 17 patients with COVID-19 who received the intervention had died.

Clinicians at NYU Langone Health had good reason to believe they could do better. A lot better. Since launching in 2014, NYU Langone’s Adult ECMO Program had a patient survival rate of 85 percent, well above that of other programs reporting to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, an international nonprofit consortium of healthcare institutions and researchers. Those results were largely reflective of the protocols used by NYU Langone to select and treat patients—specifically, picking candidates deemed as having a high likelihood of survival and recovery, and starting the therapy earlier than at most other institutions, before the lungs were ravaged beyond repair.

While COVID-19 was proving to be an unusually deadly respiratory disease, cardiothoracic surgeon Deane E. Smith, MD, surgical director of the Adult ECMO Program, and other team members believed the system in place was built to succeed. Among the 30 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 at NYU Langone in Manhattan and placed on ECMO circuits between March 10 and May 1, 2020, 27 went home and only 1 required supplemental oxygen upon leaving the hospital, according to a single-center study published in Annals of Thoracic Surgery. One year later, 26 of these patients, or 87 percent, were still alive, and those who completed follow-up pulmonary tests displayed encouraging progress in recovering normal lung function. These results are among the best ECMO outcomes at centers across the country.

“We used ECMO intentionally as an intervention, not as a last-ditch salvage therapy,” says Dr. Smith, the study’s lead author. “Our job was to identify these patients at a point where we could make a meaningful difference.”

A Rare Intervention Takes Center Stage

During the program’s first few years, ECMO for respiratory failure was a seldom-used option, provided for an annual average of about 10 patients with severe pneumonia, influenza, or respiratory failure. That number tripled with the launch of lung transplantation at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute in 2018. The procedure quickly became a proven means of helping patients recover sufficiently to have a lung transplant and, in some cases, for treating complications following transplant surgery.

That ramping up of the Adult ECMO Program enabled NYU Langone to be well prepared for the frantic COVID-19 surge in the spring of 2020, when 415 patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at NYU Langone in Manhattan, a majority of whom were placed on ventilators. In anticipation of the virus’s arrival in New York, the hospital obtained additional ECMO units on loan from other programs, enabling it to treat up to 15 patients simultaneously.

Equally essential was having a highly trained team in place: medical intensivists Ronald M. Goldenberg, MD, Nancy E. Amoroso, MD, and Anthony S. Lubinsky, MD, to evaluate patients for the therapy; Dr. Smith, to surgically connect patients to the circuit; perfusionists to operate and troubleshoot the equipment; Stephanie H. Chang, MD, surgical director of lung transplantation, poised to remove infected or damaged portions of the lungs, if necessary; and a dedicated critical care team to monitor patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. With this structure, NYU Langone’s success rate proved sustainable for patients with COVID-19—in contrast to other institutions, which, to this day, have an average ECMO mortality rate of 47 percent for patients with COVID-19. “We didn’t have to change what we did on a day-to-day basis during the pandemic,” explains Dr. Smith, associate director of heart transplant and mechanical circulatory support and associate professor of cardiothoracic surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

The Right Patient at the Right Time

Central to NYU Langone’s ECMO outcomes has been its uncommon approach to screening patients. Rather than viewing it as a desperate measure, the intensivists and cardiothoracic surgeons identified patients, ages 18 to 65, who were most likely to benefit: those with acute respiratory failure, whose lungs were unable to deliver oxygen to the blood, but who didn’t have other major complications. That meant eliminating candidates with multisystem organ failure and those in severe shock, a life-threatening condition caused by inadequate blood flow. “They needed to be sick enough that ECMO would make a difference, but not so sick that they were going to die from secondary infections, bleeding, clotting, or other problems,” explains Dr. Lubinsky, the medical director of respiratory care at NYU Langone.

One key strategy was evaluating patients within three days of intubation, compared with several weeks at many medical centers. Getting patients on ECMO at an earlier stage enabled the team to dial down ventilators to a gentler setting as soon as possible, decreasing stress and damage to patients’ lungs and enabling them to “rest” and heal. Of the 80 patients assessed during the first wave, 30 were ultimately approved for ECMO. “As a group, we decided to use the same criteria that we had prior to COVID,” says Dr. Goldenberg, clinical associate professor of medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

“We used ECMO intentionally as an intervention, not as a last-ditch salvage therapy. Our job was to identify these patients at a point where we could make a meaningful difference.”—Deane E. Smith, MD, Surgical Director of the Adult ECMO Program

Where the protocol differed was in how long patients with COVID-19 remained on ECMO. Before the pandemic, the longest duration for any patient at NYU Langone had been 50 days. Given the severity of the virus’s impact on the lungs, the critical care team, with the endorsement of hospital leadership, opted to keep patients on ECMO for as long as necessary. The median support time was 19 days, and in 3 instances, patients remained connected to the support system for more than 100 days before going home. By contrast, roughly one-quarter of patients on ECMO at other facilities were removed either to have a lung transplant or because the treatment was deemed ineffective. “We knew these patients would take longer to recover, and we gave them time to do so, providing meticulous care throughout,” says Dr. Amoroso, director of the medical ICU and section chief of the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine.

Managing Risk

Given COVID-19’s highly contagious nature, a majority of ECMO programs declined to perform two maintenance procedures that, because they permit aerosolized droplets to escape, raised the risk of viral transmission. The first, a percutaneous tracheostomy, replaces the breathing tube snaked down a patient’s throat with a surgically created opening in the windpipe, a configuration that is more comfortable for the patient and requires less sedation. To mitigate the risk, interventional pulmonologist Luis F. Angel, MD, medical director of lung transplantation, invented a shrewd workaround: placing a camera alongside the tracheostomy tube, rather than inside it, meant that the cuff holding the tube in place did not need to be deflated. Dr. Angel and interventional pulmonologist Samaan Rafeq, MD, completed more than 300 of these bedside procedures in the ICU, including on ECMO patients, usually within 2 days after beginning the therapy. An NYU Langone study published in Critical Care Medicine last year concluded that the procedure was safe and low risk for patients and healthcare providers and associated with improved clinical outcomes. “That was brilliant—a critical development for helping these patients while keeping staff safe,” says Dr. Smith.

“Our multidisciplinary team was a critical component of these results. We had the infrastructure to train large numbers of nurses to provide complex care and employed a whole team of dedicated clinicians to get these patients through and get them better.”—Anthony S. Lubinsky, MD, Medical Director of Respiratory Care

The use of bronchoscopies to clear compromised lungs of sputum and mucus to improve oxygenation and prevent opportunistic infections also carried exposure risks for the staff performing them. Still, the cardiothoracic team, led by Michael Zervos, MD, chief of clinical thoracic surgery, routinely performed them, using a rigorous protocol to reduce the potential for harm.

Remarkably, staff members did not contract COVID-19 from either of these procedures. “These patients had tenacious secretions plugging their lungs,” says Aubrey C. Galloway, MD, the Seymour Cohn Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and senior author of the ECMO study. “These treatments improved the outcomes, both for those on ECMO and for other ICU patients.”

Training an Army

ECMO is a labor-intensive enterprise, one that requires around-the-clock monitoring and regular lab testing, radiological procedures, medication adjustments, and other interventions. Much of the daily care is overseen by bedside critical care nurses, attending doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists. Some 145 critical care nurses were trained in caring for patients on ECMO during the first few weeks of the pandemic, and their skill, as well as their numbers, were essential: simply turning a patient hooked up to the complex machinery safely onto their stomach, a technique called proning, required nurses, a perfusionist, an anesthesiologist, a respiratory therapist, and physical and occupational therapists from the Safe Patient Handling and Mobility Team. Proning, designed to enhance blood oxygen levels, was used with 12 of the 30 patients.

Yet another strategy was to carefully monitor the use of anticoagulants, a standard treatment for ECMO patients to prevent blood clots, a potentially deadly complication. While many centers used only one lab marker to determine dosing, the pharmacy team at NYU Langone—leveraging previous experience with patients on ECMO—used two lab measures: one to ensure that the level was sufficient to prevent vessel blockages and another to ensure that it was not so high as to cause excessive bleeding, which could result in a brain hemorrhage.

As patients improved, Rusk Rehabilitation acute care physical and occupational therapists and speech–language pathologists, led by Jodi Herbsman, program manager for acute care rehabilitation, worked tirelessly to help them regain mobility and function. Once they returned home, pulmonologist Rany Condos, MD, director of the Post-COVID Care Program and an expert in advanced lung diseases, tracked and treated their residual lung symptoms.

“Our multidisciplinary team was a critical component of these results,” says Dr. Lubinsky. “We had the infrastructure to train large numbers of nurses to provide complex care and employed a whole team of dedicated clinicians to get these patients through and get them better.”

Dr. Goldenberg concedes that NYU Langone’s outcomes were even better than the critical care team envisioned at the dawn of the pandemic. “The disease mortality was so high among COVID patients in the ICU,” he says. “Without ECMO, almost all of these patients likely would have died, yet the overwhelming majority have done very well.”

That success is a direct result of an approach that is central to NYU Langone’s mission, says Fritz François, MD, executive vice president and vice dean, chief of hospital operations. “The NYU Langone Adult ECMO Program is an amazing example of the extraordinary outcomes that are possible when teams collaborate to think differently, perform boldly, and excel spectacularly.”