Experimental Machine-Learning Software Could Help Screen Patients for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

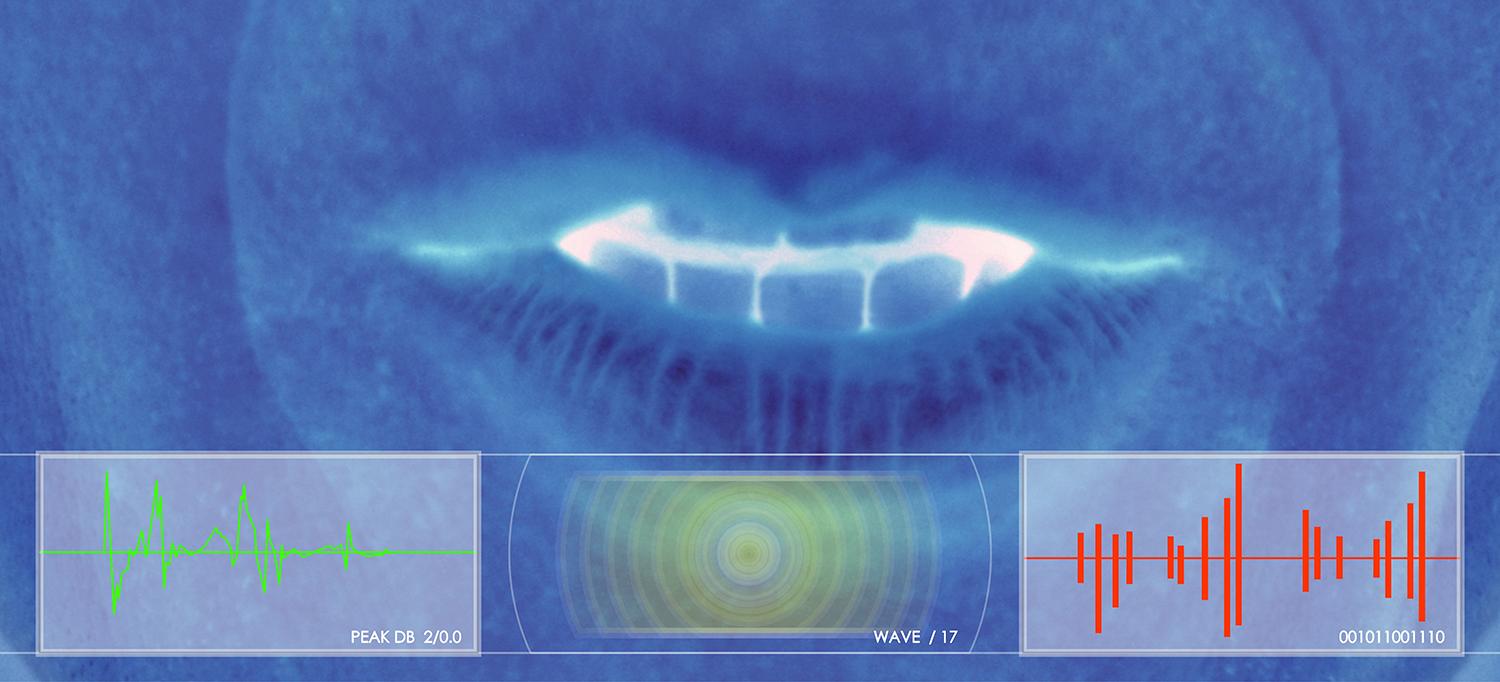

Machine learning software can pick up on vocal characteristics that help distinguish between people with or without PTSD.

Photo: Image Source/Getty

In the 1980s, as speech-recognition software began hitting the market, psychiatrist Charles R. Marmar, MD, was quick to adopt the technology. “I used one of the earliest consumer versions,” says Dr. Marmar, the Lucius N. Littauer Professor of Psychiatry and chair of the Department of Psychiatry.

It’s no wonder, then, that Dr. Marmar would think of enlisting voice-processing technology as a way to apply machine learning to one of the thorniest diagnostic challenges in modern psychiatry: post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, a potentially debilitating psychiatric condition affecting one in 13 adults in the United States.

In spite of its impact, PTSD remains an elusive diagnosis. “Normally, it’s done by interviewing patients and asking about nightmares, flashbacks, startle reactions, perceiving the world as dangerous, risk-taking behaviors, and being fearful of the future, among other indications,” says Dr. Marmar. “But because of the stigma of mental illness in much of the population, many patients underreport symptoms. In a minority of cases, they may dramatize or fabricate them. Reliance on self-reported symptoms leaves us prone to error.”

Dr. Marmar knew that as far back as the 1800s, psychiatrists had established that patients suffering from depression tend to have recognizable voice qualities. Since then, research has suggested that other psychiatric conditions, including PTSD, may carry with them unique vocal characteristics. Detecting those traits has always been a matter of the clinician’s subjective perception in patient interviews. But seeing that machine learning was making inroads into all sorts of diagnostic challenges, Dr. Marmar considered the possibility that a machine-learning program could do the detection.

Dr. Marmar started researching the question and immediately ran into a statistical dilemma. “Classically, you need 10 subjects for each variable you examine,” he explains. “But there are 40,000 variables in speech, which means I’d need 400,000 speech samples.” For his research, Dr. Marmar only had access to 150 voice samples from the U.S. military veterans who were serving as research subjects.

But help came from the nonprofit research group SRI International, makers of the iPhone’s personal assistant, Siri, which had developed new analysis techniques to study a large number of features in samples from a small number of subjects. In the end, their machine-learning software highlighted 18 vocal characteristics that helped distinguish between people with or without PTSD, coming to the same diagnostic conclusion as a clinician 89 percent of the time.

Eventually, a voice sample as short as five minutes will be needed to make a determination, and the sample could be recorded on a smartphone. “Right now, a patient has to spend 90 minutes with a psychiatrist just for an initial intake interview,” Dr. Marmar says. “This software could make the process less burdensome to those patients.” While it wouldn’t provide the final word on who does or doesn’t have PTSD, it could suggest which patients may be most in need of a full diagnostic interview.

“It’s not meant to replace a clinical interview,” explains Dr. Marmar. “But it could become an important element of the diagnostic process.” In particular, he says, the program could be ideal for screening large populations that might be at higher risk for PTSD, including military personnel and first responders.

Dr. Marmar says that it’s possible his system or another one like it might eventually be expanded and modified to screen for other psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. That could lead to an important improvement in medicine’s ability to ensure that patients who most need psychiatric help are seen by a clinician.