Increasing levels of a simplified version of “good” cholesterol reversed disease in the blood vessels of mice with diabetes, a new study finds.

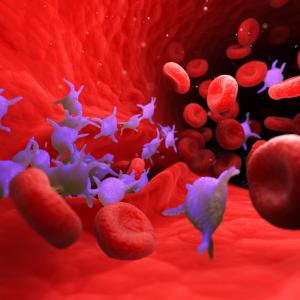

Published online in the journal Circulation on September 30, the study results revolve around atherosclerosis, a condition in which high levels of cholesterol cause “plaques” to form in vessel walls, eventually restricting blood flow to cause heart attack and stroke. Many of these same patients have diabetes, in which tissues are injured by high blood sugar.

Led by researchers from NYU School of Medicine, this study provides the “first direct evidence” that raising levels of a simple, functional version of good cholesterol—the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) shuttle that pulls cholesterol out of cells—reversed the progression of atherosclerosis in mice with diabetes.

The results, say the study authors, reflect the emerging view that HDL’s ability to extract cholesterol from cells reduces inflammation, the immune reaction in which cells rush to injury sites. Part of the natural process that repairs damaged tissues, inflammation worsens disease in the wrong place, such as plaques.

“Our study results argue that raising levels of functional good cholesterol addresses inflammatory roots of atherosclerosis driven by cholesterol buildup beyond what existing drugs can achieve,” says senior study author Edward A. Fisher, MD, PhD, MPH, the Leon H. Charney Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine in the Department of Medicine at NYU Langone Health and director of translational research with NYU Langone’s Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. “Good cholesterol is back as therapeutic target because we now understand its biology well enough to change it in ways that lower disease risk.”

Better Measures to Evaluate Drugs That Raise HDL Levels

Treatments for atherosclerosis for decades have focused on lowering blood levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) or “bad” cholesterol, a second shuttle that delivers molecules of cholesterol from the diet (and from the liver) to the body’s cells, including those in vessel walls. But the ability of treatments that lower LDL cholesterol to reduce heart attack risk is limited, and especially in adults with diabetes, who are twice as likely to die from heart disease or stroke as people without diabetes, according to the American Heart Association.

To reduce disease risk not addressed by lowering bad cholesterol, the field designed drugs that raised levels of the good cholesterol (HDL) shuttle that carts cholesterol from blood vessel walls to the liver for expulsion from the body. The two mechanisms should work together, but much-anticipated HDL-raising drugs, such as cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors, failed in 2016 clinical trials to reduce the risk of heart attack beyond what could be accomplished by lowering cholesterol.

Faced with these limits, researchers looked more closely at the roles in atherosclerosis and diabetes of inflammation. Part of this shift was the realization that old measures for how a given HDL-raising drug countered disease—such as how much of the HDL shuttle was in a person’s bloodstream—needed to be replaced. The new measure, says Dr. Fisher, should be how well a person’s HDL can pull cholesterol out of cells (total cholesterol efflux) because it better captures the inflammatory part of the disease process.

The new measure builds on the discovery that signaling proteins and fats related to high blood sugar attach to, lower the number of, and disable HDL—which is composed of a protein called apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) linked to phospholipids. This lowers supplies of the shuttle capable of achieving cholesterol efflux, termed functional HDL.

In sets of experiments, the current study authors raised functional HDL levels in diabetic mice by increasing the amounts apoA-I present, either by genetic engineering or direct injection. They found that the increase in functional HDL stopped cholesterol-driven immune cell multiplication (proliferation) in bone marrow, reduced inflammation in immune cells in plaques by half, and enhanced the reversal of atherosclerotic disease processes (regression) by 30 percent in mice already treated to lower their bad cholesterol.

Finally, the study results also show that increased HDL levels kept another set of immune cells called neutrophils from giving off webs of fibers that increase inflammation and blot clot formation in atherosclerosis, further blocking blood flow.

“For the study we built our own version of the HDL particle, called reconstituted HDL, which promises to become the basis for new kinds of functional HDL treatments that finally reduce the residual risk for cardiovascular disease not addressed currently,” says first author Tessa J. Barrett, PhD, research assistant and professor in the Department of Medicine at NYU School of Medicine.

Along with Dr. Fisher and Dr. Barrett, study authors from the Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology at the NYU School of Medicine were Emilie Distel, Michael S. Garshick, MD, and Yoscar Ogando; along with Jiyuan Hu in the Division of Biostatistics, Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, in the Divisions of Cardiology and Hematology, and Ira J. Goldberg, MD, in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism. Also study authors, were Andrew Murphy in the Division of Immunometabolism at Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Australia; Jianhua Liu in the Department of Surgery at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Tomas Vaisar and Jay Heinecke in the Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology, and Nutrition at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Funding for the study was provided by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK095684, R01 HL117226, R01 2 HL084312, PO1 HL092969, P01HL131481, and R01 HL114978; American Heart Association grants 18CDA34110203AHA, and 18CDA34080540; and by National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) grants APP1083138 and APP1106154, as well as a National Heart Foundation (Australia) grant 100440.

Media Inquiries

Greg Williams

Phone: 212-404-3500

gregory.williams@nyulangone.org