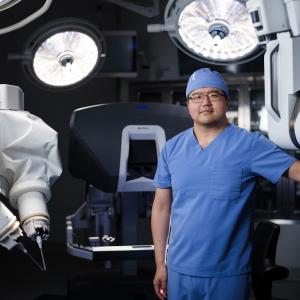

PHOTO: NYU LANGONE STAFF

Running had always been a big part of her life, so when Tammy Fabish began feeling queasy during her runs, the New Jersey mother of three knew something was off. Even walking hand in hand with her preschool-aged twins felt physically taxing. When one boy lurched forward, she would lose her balance. She figured her mom-on-the-go lifestyle was getting the best of her: “I wasn’t sleeping well, I wasn’t taking care of myself, and then COVID hit.”

In 2021, Tammy began seeing doctors again, among them an ear, nose, and throat specialist near her Morris County home. The hearing in her right ear seemed muffled. She thought she needed earwax removal, but that wasn’t the problem. A brain MRI revealed a vestibular schwannoma, also known as an acoustic neuroma. This type of tumor sits on the vestibulocochlear nerve, which runs from the inner ear to the brain. It plays a role in hearing and balance.

Neither she nor her husband, William, her longtime running partner, were prepared for the diagnosis. “Never in a million years did I imagine I had a brain tumor,” the now 49-year-old concedes. “I kind of went into shock.”

Acoustic neuromas are noncancerous but can lead to ringing in the ear and hearing loss, as well as vertigo and balance issues. Left untreated, the tumor can grow and compress the brain and nearby nerves that control facial movement and sensation, speech, and swallowing. An estimated 1 in 100,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with these tumors each year.

A friend insisted on driving Tammy into Manhattan to consult the experts at NYU Langone Health who specialize in treating these tumors. After meeting with Donato R. Pacione, MD, associate professor in the Department of Neurosurgery, and David R. Friedmann, MD, associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Tammy knew she was in the right place. “If someone’s touching my brain, I want it to be them,” she concluded. “They really listened to who I am as a person. I felt so heard.”

A Smile-Saving Surgery

For small, asymptomatic acoustic neuromas, doctors often suggest watchful waiting. But considering Tammy’s balance and hearing issues and the size of the tumor—about 2 centimeters across—her surgical team recommended either Gamma Knife radiosurgery to destroy the abnormal tissue and stop the mass from growing, or surgery to remove it entirely.

“They really listened to who I am as a person. I felt so heard.”

—Tammy Fabish

Tammy decided to have the tumor removed. But how, exactly? Her surgeons explained the options. One would be to reach the tumor by way of the inner ear, reducing the risk of severing or otherwise damaging the thin nerve that controls the muscles of the face. “A translabyrinthine approach allows us to identify the facial nerve much earlier in the procedure, resulting in better facial nerve outcomes,” explains neurotologist Dr. Friedmann, who specializes in the treatment of conditions affecting hearing, balance, and the vital structures at the skull base. This approach made sense, as Tammy’s hearing had already declined.

The other option, a retrosigmoid approach, would mean taking a more circuitous route to the tumor, through the occipital bone in the back of the head. This hearing-sparing surgery is often the choice when patients still have hearing that can be preserved.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario,” notes Dr. Pacione, a neurosurgeon specializing in skull base surgery. “If you don’t take into account people’s goals and their values, you won’t be doing them a service.” To Tammy, the choice was clear: “At the end of the day, I’m a substitute teacher for little kids, and I smile a lot with my own kids,” she says. “I really wanted my smile.”

On October 15, 2021, a multidisciplinary team gathered in NYU Langone’s Kimmel Pavilion for the roughly four-and-a-half-hour surgery. It began with an incision behind Tammy’s ear. For the next hour or so, Dr. Friedmann drilled away bone, working around important blood vessels, clearing a direct path to the tumor, and identifying the facial nerve that the team would protect throughout the procedure. This allowed Dr. Pacione to open the outer covering of the brain to access the brainstem and separate and remove the tumor from surrounding nerves.

Tiny electrodes placed in Tammy’s facial muscles made it possible for neurophysiologists in the room to monitor her facial muscle contractions during the procedure and provide real-time feedback to the surgical team. Abdominal fat was removed from a small incision just below her belly to help seal the bony opening at the end of the procedure. This would prevent cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain, from leaking out.

Adjusting to a New Normal

In the first month after surgery, Tammy would see her kids off to school and then go back to sleep or sit quietly to recover. “I felt completely overwhelmed,” she recalls. “My brain was trying so hard to rework itself.”

With the vestibular system in her right inner ear out of commission from the tumor, Tammy’s brain had to rely on the left side for information to help with movement and balance. “It’s exercising the good side instead of trying to make sense of the bad side,” says Dr. Pacione.

By January, Tammy was cautiously pounding the pavement again. “I was very conscious of every little dip in the sidewalk. It was almost like talking myself through the run, telling my brain what my eyes were seeing.”

These days, running comes naturally. So, when the opportunity arose this April to run the Jersey City Marathon, Tammy didn’t hesitate. She crossed the finish line more than 5 hours later, greeting her husband, 10-year-old daughter, and 7-year-old twins with a wide grin. “I was just so excited to accomplish my goal,” she says. “I was running again, and I realized that there is a world where I’m still going to have this piece of me.”

Expert Care and Kindness

Initially, Tammy had been reluctant to travel to New York City for treatment. Now she praises every detail of her NYU Langone experience, from the surgeons who removed the tumor from her brain to the security guard who escorted her to the elevator bank during his lunch break. “People were so nice to me at every turn,” she says.

It wasn’t just kindness that won her over. Tammy benefited from a team-based approach, pairing the surgical expertise of a neurosurgeon and a neurotologist. Plus, because NYU Langone is a referral center, our surgeons perform more than 100 acoustic neuroma surgeries a year, and help care for an even greater number of patients having radiosurgery or being carefully watched with regular imaging.

“It was an amazing experience to have these brilliant, renowned doctors care about what I wanted out of this,” she adds. “We talked about every little detail.” And that is something to smile about.