Neurosurgeon Dr. Chandra Sen’s vast surgical expertise guides the safe resection of a challenging tumor.

Photo: Joshua Bright

When intensifying symptoms associated with a right-sided meningioma involving the orbit and brain led to functional decline, a 44-year-old female patient traveled to New York City from the United Arab Emirates for treatment. The tumor’s magnitude and rare orbital location presented a surgical challenge that required an open approach—a complicated operation requiring the delicate hands of an experienced, multidisciplinary surgical team capable of resecting the tumor and mitigating postsurgical cosmetic effects. Combining neurosurgical precision and nuanced reconstruction techniques, the team executed a carefully planned approach and safely resected the patient’s tumor, restoring both her function and her appearance.

Meningioma Location Compounds Surgical Complexity

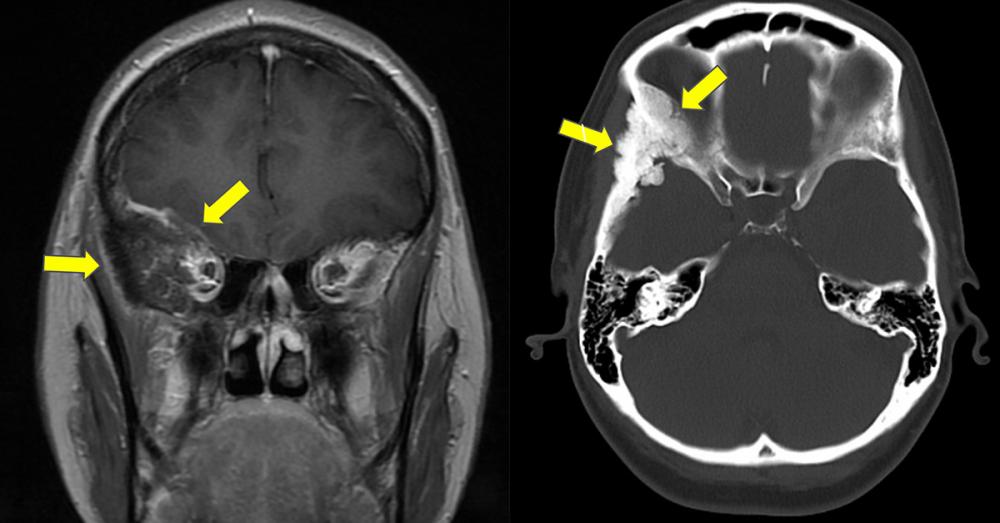

A 2014 MRI had revealed a rare, right-sided spheno-orbital meningioma in the context of recurring symptoms that included neck pain and recurring headaches. In light of the complexities of resection and the patient’s otherwise good health, her care team in the United Arab Emirates recommended watchful waiting.

Over time, the patient’s symptoms progressed, leading to proptosis of the right eye, facial numbness, and increasing pain. Serial imaging showed progression of the tumor, and the patient traveled to the United States for consultation with NYU Langone neurosurgeons, scheduling her subsequent surgery with Chandra Sen, MD, professor in the Department of Neurosurgery and director of the Anterior Skull Base Surgery Center.

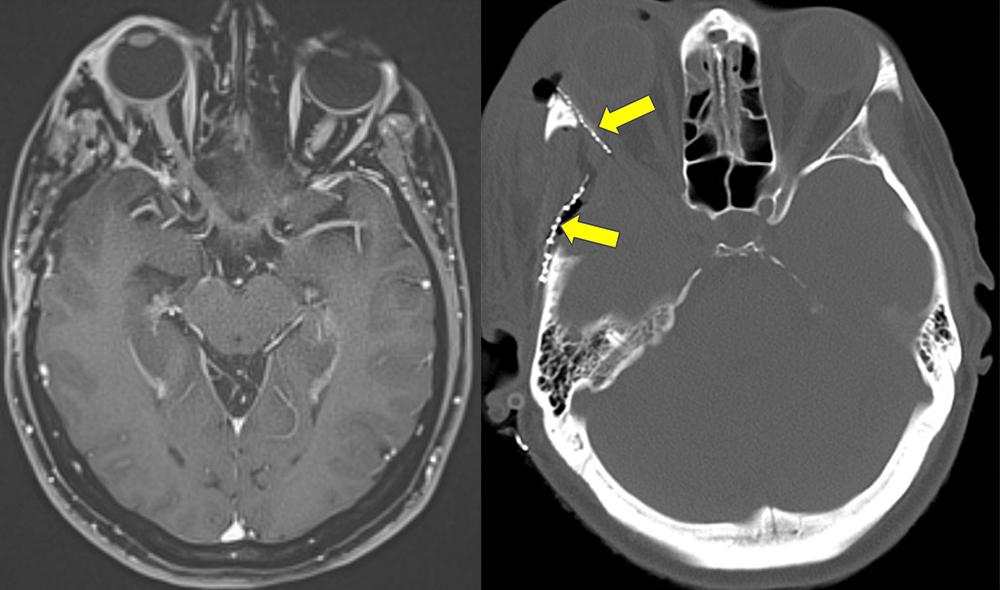

With an in-depth review of the patient’s history and new imaging studies, Dr. Sen confirmed a right-sided en plaque sphenoid wing meningioma with marked hyperostosis of the lateral and superior orbital walls. Though a thin layer of the tumor involved the periorbita on the right side, it did not appear to involve the optic nerves or the cavernous sinus.

The surgical challenge of resecting this type of benign tumor lies in both its extent and its delicate location at the base of the brain and orbit; aggressive action must be balanced with the preservation of critical function. “This was not a minimally invasive surgery—the tumor was like a pancake expanding over a large surface area, which necessitated a large craniotomy,” explains Dr. Sen. “Navigating around critical structures to remove a tumor like this relies purely on expertise developed through experience.”

Weighing the Risks of a Complex Surgical Intervention

Dr. Sen counseled the patient on the complexities of the extensive cranial resection—including risk of injury to the eye, optic nerve, and brain—and the cosmetic implications of reconstructing the orbital wall. Although the team’s depth of experience would mitigate much of that risk, he explained, long-term postsurgical effects, such as double vision, were possible.

Inaction, on the other hand, carried its own risks. Although the tumor was benign, its progressive growth would eventually lead to vision loss and neurological issues, and the protrusion of the eye would become disfiguring. An incomplete tumor resection would likely result in its regrowth, potentially necessitating radiation treatments that could be detrimental to the eye and the brain.

With the risks weighed, an aggressive surgical approach, in collaboration with plastic surgery for facial reconstruction, was deemed the best option for tumor removal, vision preservation, and a good aesthetic outcome. The surgery was scheduled for a subsequent trip.

Careful Resection and Reconstruction Target Function and Appearance

A surgical plan was developed, with the assistance of David A. Staffenberg, MD, professor in the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery and Department of Neurosurgery, wherein complete tumor removal would be followed by reconstruction of the surgical defect to restore the patient’s appearance and function.

Dr. Staffenberg began the skin incision with Dr. Sen—in order to properly perform the closure after reconstruction—opening the patient’s cheekbone and orbit. Dr. Sen raised a wide frontotemporal bone flap to gain access to the plaque extension of the tumor into the convexity dura.

The lateral wall of the orbit and the involved bone were drilled away under magnification, exposing the superior orbital fissure where the tumor was involved. The periorbita involved by the tumor was removed, with the muscles and nerve of the orbit preserved. The convexity dura was excised along with the en plaque meningioma. Dr. Sen inspected the dural edges to ensure complete resection, and the orbital apex was observed to be free of tumor. With complete resection confirmed, the reconstruction process could begin.

Dr. Staffenberg harvested fat from the patient’s abdomen, and the dura was reconstructed with pieces of AlloDerm™, flapped downward toward the orbital apex. “We wanted to fill in the defect that was left behind once the tumor was removed,” explains Dr. Staffenberg. “It’s important to have good contour and support for the eye.”

The orbital wall was reconstructed with an implant, with careful inspection for good symmetry between the two orbits. The AlloDerm™ over the orbital apex was laid on top of the implant, and the fat graft was placed. The temporalis muscle was resuspended, and the orbital zygomatic bone was plated back with the orbital reconstruction. With a subgaleal drain left in place and the abdominal wound and scalp closed, the eight-hour surgery was complete, and the patient was moved to recovery.

Experience Informs an Excellent Outcome

Preoperatively, Dr. Sen cautions patients that their postoperative course may be more challenging than anticipated. “Before the operation, these patients’ involved eye is fully open and everything is more or less working except for some vision impairment,” he says. “After the surgery, the eye is closed and they can’t see properly. So I prepare them for the challenges that accompany a normal course of recovery.”

As expected, this patient’s right eye was completely closed due to the surgical trauma to the oculomotor nerve, but she was otherwise alert with mental function intact, and she was ready for discharge five days after surgery. Her eye began opening approximately one month postoperatively, and she was able to travel home about two and a half months after surgery, following minor reconstructive procedures performed by Dr. Staffenberg. Once home, the patient continued to regain her vision, with full recovery of eye function.

“Notably, most of the recovery occurs naturally as the eye muscle returns to normal strength and the brain’s wiring intrinsically works to move both eyes in tandem,” explains Dr. Sen. “Like all patients, she had to wear a patch initially as she walked so her double vision wouldn’t cause dizziness, but she did not require any special rehabilitation.”

For this patient, it was Dr. Sen’s expertise, gained through deep experience with this complex open surgery, that informed the careful navigation of critical neural and orbital structures needed to safely and completely remove her tumor. “Even as technology enhances our approach and outcomes in the context of other conditions, there remain some operations, like this one, that rely completely on the skill and precision of an experienced multidisciplinary surgical team,” concludes Dr. Sen.