Nicola Fabbri, MD

Photo: NYU Langone Staff

An orthopedic surgeon who specializes in limb-preserving reconstructive surgery for people with bone and soft tissue cancer, Nicola Fabbri, MD, joined NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in September 2022. Dr. Fabbri serves as a professor in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and chief of the Division of Orthopedic Oncology. Previously, he was a professor and attending surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Dr. Fabbri’s practice is dedicated to musculoskeletal tumors. He treats people with sarcomas, a heterogeneous group of primary malignancies of bone and soft tissue, as well as people with metastatic cancer to bone.

Here, Dr. Fabbri discusses his interest in focusing on musculoskeletal cancers, advances in the field of limb-preserving reconstructive surgery, and more.

What is your background and where did you do your medical training?

I was born and raised in Bologna, Italy, where the world’s oldest university and the Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute, one of the largest orthopedic hospitals in the world, are located. After medical school, I did my orthopedic surgery training there with Dr. Mario Campanacci, who was a pioneer in musculoskeletal oncology. Dr. Campanacci embraced the concept of a multidisciplinary approach in oncology. Today, this concept is widely acknowledged and part of everyday clinical practice, but it was a novel idea and approach in the 1960s and early ’70s.

Dr. Campanacci understood the value of chemotherapy in several of these conditions, and that made a big difference in survival. Ultimately, with the use of chemotherapy, surgery, and sometimes radiotherapy, the concept of limb-preserving surgery—as opposed to amputation—for osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and other primary bone malignancies was developed and blossomed throughout the decades leading to the 1990s.

He encouraged me to apply for fellowship at the Mayo Clinic, where I ended up doing actually two fellowships back to back in adult reconstruction and musculoskeletal oncology. There, I improved my skills as a reconstructive surgeon. I learned a lot about joint replacement and reconstructive surgery in general and greatly supplemented my earlier training in musculoskeletal oncology.

I returned to Bologna, where I became faculty at the Rizzoli Institute for more than 10 years before joining the staff of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. I was at Memorial Sloan Kettering for a little more than a decade, and I accomplished a lot. I became a much better surgeon, clinician, and researcher. I also have developed a better understanding of cancer well beyond musculoskeletal oncology thanks to my time at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

What inspired you to become an orthopedic cancer surgeon?

It was the classic scenario: a medical student meets an engaging and fascinating mentor–leader, who then follows in the mentor’s footsteps.

In medical school, during my orthopedic surgery rotation with Dr. Campanacci, I saw the difference chemotherapy and reconstruction of long bones and muscle was making in children with osteosarcomas. Data had already established that chemotherapy and surgery increased survival for osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma from 10 to 15 percent at most, following amputation, to 65 to 70 percent and preserving their limb. For me, it was an epiphany seeing these kids surviving and returning to the clinic years later. They were alive with a reconstructed extremity that allowed them a sedentary but otherwise quite reasonable quality of life.

What was the effect of the advances in chemotherapy and limb-preserving surgery for people with musculoskeletal cancers?

During the mid- to late-1980s and 1990s, different clinical trials established that the combination of chemotherapy with limb-preserving surgery, compared to amputation and chemotherapy, was associated with a survival rate well above 60 percent, and closer to 65 to 70 percent. Over time, step by step, survival has increased further. Now, the cure rate has plateaued, and we often complain it has not significantly improved in the last 20 years or so. In reality, survivorship has marginally improved for patients that relapse, but not substantially, while the proportion of patients continuously disease-free has not significantly changed in 20 years. These figures and data are for us surgeons and clinicians the drive to succeed in moving the needle and advance the field.

What types of musculoskeletal cancers do you treat?

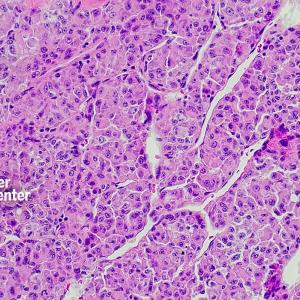

The focus of my research and clinical activity for most of my career has been on sarcomas, because that’s where I think surgery, in combination with chemotherapy, makes a difference between life and death. All bone sarcomas are by definition very rare malignant tumors, with incidence in the single digits per million for each condition. They include a few entities and among others: osteosarcoma, a malignancy whose cells produce immature bone called osteoid; Ewing sarcoma, a cancer related to hematologic malignancies such as lymphomas and composed of small round blue cells; chondrosarcoma, whose cells produce and are embedded in a cartilaginous matrix; angiosarcoma, characterized by cell and tissue architecture presenting variable degrees of similarity with normal blood vessels; and an extremely rare and challenging tumor called chordoma, for the treatment of which we have established a comprehensive chordoma treatment group at NYU Langone.

Chordomas variably occur along the spine, from the base of the skull to the sacrum and coccyx, often referred to as the tailbone. Surgery remains the primary treatment for chordoma. I collaborate with two neurosurgeons at NYU Langone, Dr. Chandra Sen (the Bergman Family Professor of Skull Base Surgery in the Department of Neurosurgery and director of the Benign Brain Tumor and Cranial Nerve Disorders Programs) and Dr. Ilya Laufer (associate professor of neurosurgery).

The NYU Langone chordoma program relies on a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to enhance individualized treatment in all anatomic locations and stages of the disease. Besides neurosurgery and orthopedic surgery, the program involves radiation oncology, sarcoma oncology, pathology, and basic research.

I also treat metastatic cancer to bone, which is much more common than primary bone or soft tissue tumors. At NYU Langone, we have recently established the Bone Extremity and Spine Tumor Program (BEST Program). This initiative, coordinated by Dr. Abraham Chachoua (the Antonio Magliocco Jr. Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine, professor in the Department of Urology, and associate director of cancer services at Perlmutter Cancer Center), aims to provide timely multidisciplinary assessment for patients with any type of bone cancer in any anatomic location. Patients are seen the same day at the cancer center by a multidisciplinary team including neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, radiation oncologists, and palliative care providers to offer immediate relief and optimize triage and subsequent clinical management, often including medical oncology and other areas of medicine. Significant work has been devoted to this effort, which we believe will improve the quality of care of patients with primary and metastatic bone malignancies.

In general, one measure of the quality of a cancer center is the number of sarcomas that are treated. Sarcomas account for more than 20 percent of all pediatric solid malignant cancers but less than 1 percent of all adult solid malignant cancers. One could imagine that because sarcomas are so rare, the centers that treat the highest number of them are the more qualified, and to a large extent this is true.

I am extremely proud that the number of musculoskeletal cancer cases in general, and sarcomas in particular, has really boomed since I joined the group. Believe me, this is not false modesty, and it’s not simply because I came here. This is the result of the effort that NYU Langone and Perlmutter Cancer Center have made in their outreach efforts to let providers at all of the cancer center’s locations know that we have a musculoskeletal oncology group and that we can handle essentially any type of case. The oncologists at the cancer center’s locations throughout Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Long Island—and I am seeing patients on Long Island once a week—have been very receptive toward this information. I can see that the flow of patients and the number of referrals to our group has increased. This has been a remarkable effort and the perfect example of teamwork that we only intend to expand further.

What advances have you seen in the treatment of musculoskeletal cancers?

For people with metastatic bone disease, the goal remains to assess bone stability and the risk of pathologic fracture, namely a fracture caused by cancer-induced bone destruction rather than trauma. Surgery is often necessary to prevent an impending—or fix an actual pathologic—fracture, which may be the presenting event of patients with metastatic cancer to bone. Preserving or restoring mobility, ambulatory function, and independence are critical for quality of life and also life expectancy of these patients, as life and motion are inextricably connected.

Remarkably, life expectancy after pathologic fracture is now much longer than it was in the mid- to late-1990s, when reported average survival was only nine months.

In general, I think the field has advanced as a result of more effective integrated multimodal treatment in medical oncology, surgery, and radiation oncology. More recently, improved chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and biologics have played a very important role as well as new modalities of radiation therapy.

In the field of sarcomas, the field has not advanced as much, but it has advanced to some extent for patients that relapse. We have become more aggressive in the surgical management of metastatic sarcomas to the lung, the most common site of relapse for sarcomas. Repeat thoracotomy and now video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and in some instances availability of effective second-line chemotherapy have unquestionably improved survival in patients after relapse.

I also think training the next generation of surgeons or surgeon–scientists will lead to advances in the field. This is my own perspective, but I believe the commitment for education is even stronger than it was 10 or 15 years ago.

What do you bring to Perlmutter Cancer Center in terms of treating musculoskeletal cancers?

I have expertise in handling complex surgical cases. I have been fortunate in my career to have always worked at a busy cancer center or hospital, which is critical to developing this expertise—and to developing surgical and clinical skills in general. I bring to Perlmutter Cancer Center a clinical and research background that hopefully will increase our potential to attract patients and expand our outreach in the New York City area. Ultimately, I think we’re well-positioned to make a difference in the field in general.

For example, I am collaborating with Dr. Philipp Leucht (the Raj-Sobti-Menon Associate Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and associate professor in the Department of Cell Biology) and Dr. Pablo G. Castaneda (the Elly and Stephen Hammerman Professor of Pediatric Orthopedic Surgery and chief of the Division of Pediatric Orthopedic Surgery). This partnership might help us better understand bone repair and how to boost bone growth, which is a potential strategy to correct bone defects, not only for cancer, but also for trauma. Ultimately, I am an orthopedic surgeon with a broad interest in the field, not only a cancer surgeon, and this provides a unique opportunity for research, professional growth, and, in the end, for the patients.

Can you talk more about how the intersection between Perlmutter Cancer Center and NYU Langone’s Department of Orthopedic Surgery will benefit people with musculoskeletal cancers?

The synergy between the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, which is the largest department at an academic medical center in the country, and Perlmutter Cancer Center is exemplified by the array of services we can offer. I have the privilege of working with my colleagues Dr. Jacques H. Hacquebord (associate professor of orthopedic surgery and associate professor in the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery and chief of the Division of Hand Surgery) and Dr. Omri B. Ayalon (clinical assistant professor of orthopedic surgery), who both co-direct the Center for Amputation Reconstruction. Together, we will be able to offer a new technique called osseointegration, which seeks to improve function and quality of life for people who have sustained an amputation, by enhancing the connection between limb and prosthesis. This technique has mostly been applied to young veterans who have lost their limbs and has the capacity to greatly enhance the function of prostheses for them. I believe there is also a role for osseointegration in the treatment of patients with musculoskeletal cancer who have lost their limbs or are in need of an amputation after failure of limb-preserving surgery.

We currently have a broad array of expertise, and we may offer a variety of reconstructive strategies. These range from metal implants to various biologic options, including bone reconstruction by vascularized autograft, which uses the patient’s own bone and associated blood vessels; bone regeneration and transport, or bone lengthening; allograft, which uses bone tissue from a donor; and a combination of these modalities. Our goal is to provide an individualized treatment approach to each person we care for, what I often call “precision surgery.” We strive to apply these techniques selectively and provide tailored treatment based on diagnosis, location, and extent of disease, to match the patient’s age, activity level, expectation, comorbidities, and other factors potentially affecting individualized surgical treatment.

This vision now includes selective use of osseointegration, with the goal of transforming an amputation into a reconstructive and more functional procedure.

What types of treatments are on the horizon that might be beneficial for people with musculoskeletal cancers?

There will be an increasing role for multimodal treatment in which surgery remains very important, but is more and more tailored to the patient’s needs and probably less invasive. For example, we are discovering more and more genetic variants of the cancers we treat and, in parallel to these discoveries, targeted drugs inhibiting specific cellular activities and metabolic pathways.

This will possibly increase response and cause a paradigm shift in how we treat musculoskeletal cancers, just as it has changed how we treat lung cancer and other malignancies so far. Understanding how a specific type of cancer is particularly sensitive to a certain drug or a certain modality of radiotherapy, or the two combined, may increase local response of the cancer and influence our approach to surgery.

Using lung cancer as an example, metastatic bone lesions caused by EGFR-mutant and ALK fusion-positive variants of non-small cell lung cancer often do not require radiotherapy upfront because of the dramatic response of the tumor to a specific medication known as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which targets the tumor with high sensitivity. I think we will eventually see some comparable examples also in the treatment of sarcomas and other types of cancer.

In some cases, we already perform a less invasive surgery tailored to the patient’s needs. In people with chondrosarcoma, for example, we sometimes perform a pelvic resection or removal, also known as an internal hemipelvectomy. However, this is a very invasive procedure, and some patients, such as those who are older and don’t spend as much time on their feet, could benefit from a simpler and smaller surgery that removes the cancer or most of it but doesn’t involve a formal major skeletal reconstruction of the pelvis and hip to preserve function. This type of reconstruction lengthens the patient’s time on the operating table and exponentially increases the risk of perioperative complications. Balancing cancer therapy and its morbidity in the light of the patient’s function and life expectancy is key to individualized and optimal treatment. I think we will see more and more examples where we will tailor surgery to the needs of the patient.

What research projects are you involved in?

Historically, the primary focus of my research has been on bone and soft tissue sarcomas. However, over the last decade, I have largely expanded my interest in metastatic cancer to bone. I have been involved in a variety of studies focusing on prognostication and surgical management of bone metastasis. We have demonstrated that, particularly in the pelvis, fixation by a minimally invasive approach with computer-assisted navigation is beneficial in selected circumstances. I am not alone. There are other surgeons in the country who practice this, but I have been among the first to adopt this technique.

I have also been involved with research on treatment of pelvic and sacral tumors. This remains a niche of expertise that is not offered at many centers. We clearly have established NYU Langone and Perlmutter Cancer Center as a referral center to treat these challenging tumors.

A great addition to the faculty has been Dr. Bashar A. Safar (clinical professor in the Department of Surgery and chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery). We have combined clinical expertise and synergy for treatment of patients with recurrent colorectal cancer requiring a sacral resection. This challenging and technically demanding type of treatment is not offered at many cancer centers, but it is now available at NYU Langone.

We are also working on a multimodal approach, in combination with complex limb-preserving surgery, to enhance the tumor’s response and shrinkage after chemotherapy for patients who otherwise would be at risk for amputation. We are working on a clinical trial in this area for people with tumors in the extremities and, if positive, we will explore the same approach for other parts of the body.

This goes back to the synergy with the Center for Amputation Reconstruction I mentioned previously. Although this is a niche in my practice, it is a major goal for the Center for Amputation Reconstruction, and I think it is critical for patients to have a place to go if they are at risk of an amputation due to bone or soft tissue tumors, even if it’s a rare occurrence nowadays. This widens the array of options and tailored treatment we can offer to our patients.