NYU Langone’s Neuroscience Institute Has Been Relaunched as the Institute for Translational Neuroscience, Signaling a New Effort to Connect Basic & Translational Research Networks

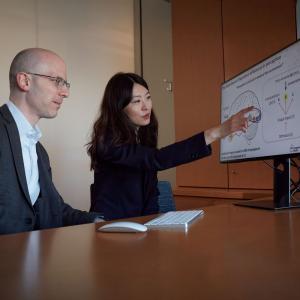

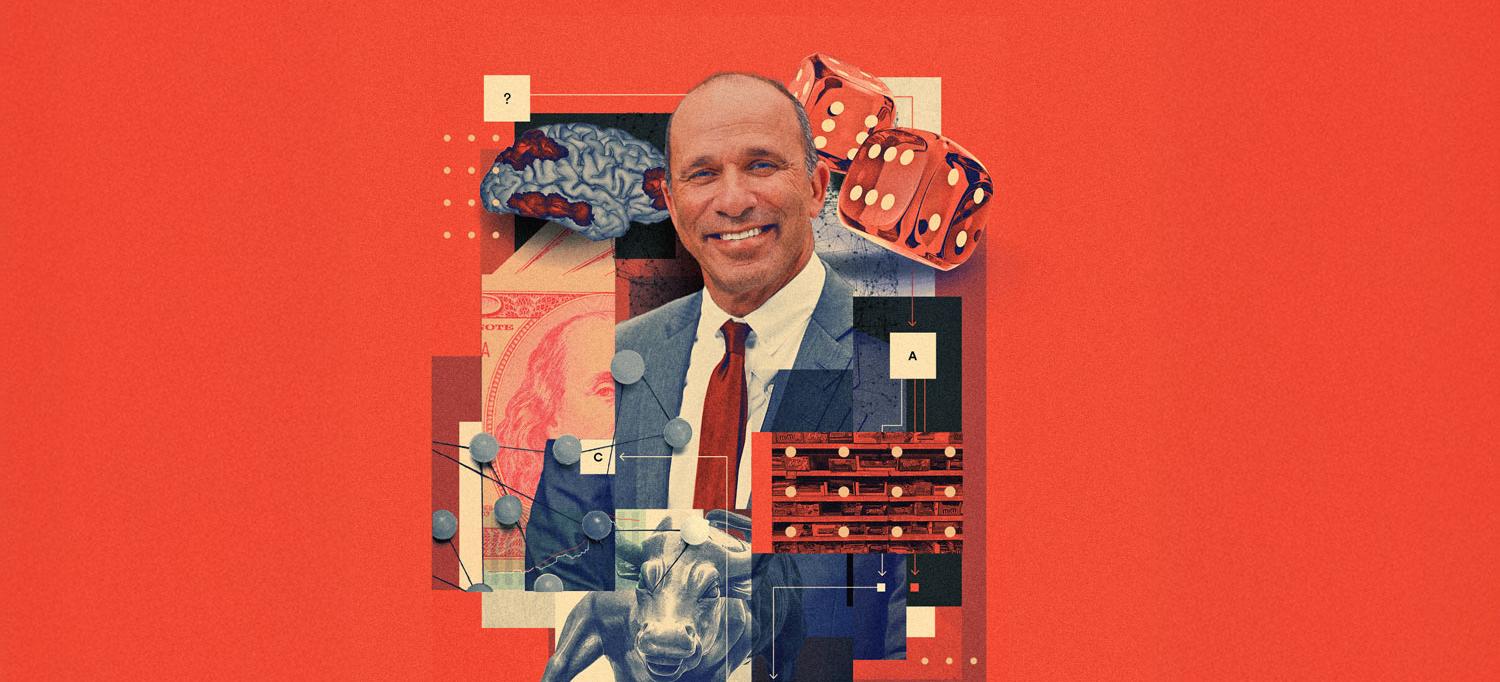

Paul W. Glimcher, PhD, director of the new Institute for Translational Neuroscience and chair of the Department of Neuroscience and Physiology, hopes to break down silos between basic and translational and clinical researchers to advance effective therapies for an array of neuropsychiatric conditions.

Credit: Neil Jamieson

Paul W. Glimcher, PhD, is regarded as the founder of neuroeconomics, which bridges neuroscience, psychology, and economics to understand how humans make challenging choices. In 2004, Dr. Glimcher established what is now known as the Institute for the Study of Decision Making at NYU, and since 2010 he has served as the Julius Silver Professor of Neural Science at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Last year, he was named to two additional prestigious posts: chair of the Department of Neuroscience and Physiology and director of the Neuroscience Institute, whose mission is to foster collaboration between nearly 1,000 basic, translational, and clinical neuroscientists.

In December 2024, the institute was relaunched as the Institute for Translational Neuroscience, signaling a new initiative to connect basic and translational research at NYU Langone. We spoke with Dr. Glimcher about that transformation, its potential significance for the future of medical science and patient care, and how his expertise on the complexities of decision-making prepared him for this new role.

Is there a message behind the rebranding of what is now called the Institute for Translational Neuroscience?

Absolutely. The name change signifies an intensified commitment to finding better treatments for an array of neuropsychiatric conditions that afflict millions of people around the world—including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It also reflects a new strategy for achieving that goal.

Could you describe that strategy?

In recent years, scientists have made tremendous progress in understanding the mechanisms behind these conditions. Yet we’ve made far less headway in finding effective therapies. One important reason is lack of integration. Basic neuroscientists study the fundamental workings of the nervous system, while translational and clinical neuroscientists develop and test novel treatments, respectively. But seldom do they work together. The Institute for Translational Neuroscience will help correct this deficit by building networks between basic, translational, and clinical researchers. Although there are a few institutes with similar names at other academic medical centers, they tend to focus exclusively on translational scientists. Ours is the first to base its approach on breaking down the silos between the basic and the translational and clinical researchers.

What’s your overarching vision for the institute?

We hope to do for neuroscience what the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has done for cancer research in recent decades. If you visited, say, a university department of cell biology or biochemistry in the 1980s, they might have been studying cancer-related proteins as an academic undertaking, but they weren’t thinking about clinical applications. Now, thanks largely to NCI initiatives, basic research departments are interlocked with clinical departments in networks dedicated to improving cancer diagnosis and treatment. As a result, cancer mortality is declining, and the number of cancers we can cure is steadily increasing.

Why is NYU Langone uniquely equipped to take on this formidable challenge?

Our institution helped launch the modern field of neuroscience in the 1970s with breakthroughs in motor control, vestibular function, and later, synapses. Our NIH funding for basic neuroscience alone has grown to $35 million annually as we’ve expanded one of the world’s premier neuroscience departments. We have spectacular basic science labs in the Department of Neuroscience and Physiology. On the other side, our translational and clinical neuroscience researchers are doing incredible work in neurology, psychiatry, rehabilitation, and anesthesiology. By connecting both sides in a systematic way, we can move more rapidly toward making a real difference in patients’ lives.

How will you unify and motivate such a large, scientifically diverse community to accomplish this ambitious plan?

Our strategy is to identify four areas each year in which NYU Langone’s research shows translational promise, starting with stroke, pain, stress, and epilepsy. We’ll assemble a think tank of 50 scientists for each area who will develop collaborative projects. The stroke team, for example, brings together basic researchers who study how brain cells respond to injury and translational and clinical researchers from neurology and Rusk Rehabilitation who investigate ways to improve postacute care. We’re aggressively recruiting scientists who excel at building bridges between disciplines. We’re creating technical cores to provide our think tanks with targeted and improved services in areas like neuroimaging and quantitative analysis. And to spur broader interest, we’re hosting a colloquium series where each group, starting with the stroke network, will present its most exciting work. This is an opportunity to build community across our neuroscience ecosystem, show what we’re capable of, and inspire people to think about new ways to connect the basic and clinical neurosciences.

Can you explain what kinds of real-world applications will result from these synergies?

We aim to develop new drugs, diagnostic tests, and other interventions for conditions such as schizophrenia and PTSD, where therapeutic options remain severely limited. We also expect to develop more and better options in areas such as mood disorders and Parkinson’s disease, where the existing treatments aren’t as effective as they could be or don’t work well for all patients.

How does this initiative relate to your work in neuroeconomics?

I know firsthand how rewarding it can be to cross academic boundaries. I initially trained as a neurophysiologist, but when I was an assistant professor, I also trained in psychology and economics while investigating the brain circuitry behind human decision-making. It was challenging, but that multidisciplinary approach has proved terrifically fruitful.

Can you share some of your own breakthroughs?

My lab does both basic and translational research. Using behavioral studies and methods such as single-neuron recording and fMRI imaging—a noninvasive technique that measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow—we’ve found that subcortical structures such as the striatum and the hypothalamus play key roles in decision-making, in concert with the dopamine reward system. That circuitry is involved in the choices people make about everything from the stock market to substance use. Beyond this, we’ve learned how to tell when the process is likely to go awry. We recently designed a decision-making game that predicts when a patient being treated for addiction is within seven days of a future relapse. In addition, we’re developing a test that monitors patients’ depression severity using a smartphone app. Once completed, it could alert clinicians to the need to adjust a patient’s medication much sooner, potentially averting a crisis. We know enough about the brain now to come up with meaningful solutions, and we’re beginning to do just that.