Pulmonologists at NYU Langone are studying gene expression and lung microbiome markers in people with and without lung cancer.

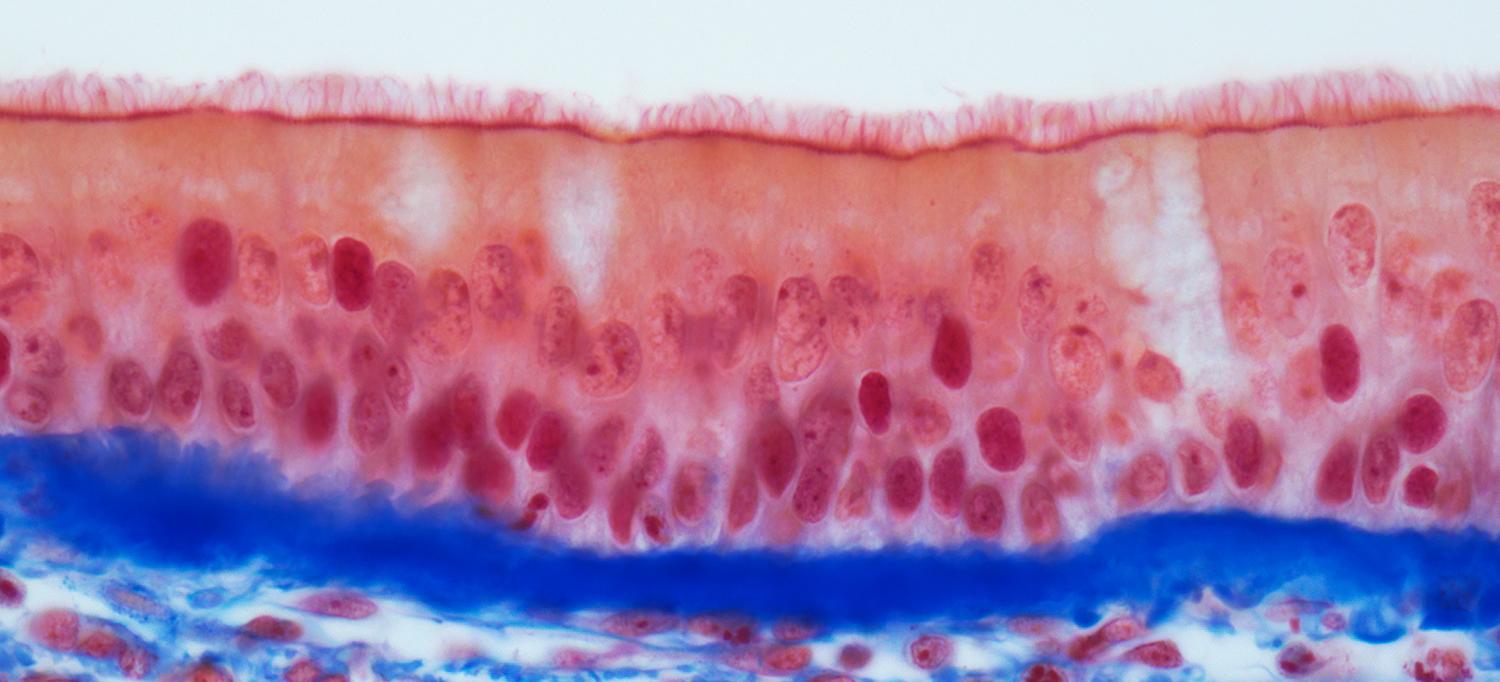

Photo: STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty

For advanced non-small cell lung cancers, immunotherapy has improved treatment options while surgical resection has provided a lasting cure for a majority of early-stage cancers. Patient outcomes can be highly variable for unknown reasons, however. After Leopoldo N. Segal, MD, associate professor in the Department of Medicine at NYU Langone, and other researchers discovered that the lungs harbor their own microbiome, investigators began delving into how dysbiotic shifts in the lung flora may alter tumor growth and the host immune response. Dr. Segal and Jun-Chieh J. Tsay, MD, assistant professor of medicine, are now zeroing in on microbial and host signatures that could help explain divergent outcomes in both immunotherapy-targeted, advanced-stage cancers and in resectable early-stage cancers, potentially opening the door to more predictive biomarkers and personalized therapeutics.

Linking the Lung Microbiome with Response to Immunotherapy

Through his longstanding work with the extensive NYU Lung Cancer Biomarker Center, which has enrolled about 16,000 patients since 2001 as part of the Early Detection Research Network, Dr. Tsay has focused on potential biomarkers in the airway. “We’ve been doing bronchoscopies to collect airway epithelial cells and initially looking at gene markers to see if there’s any correlation with early cancer detection,” he says. In collaboration with Dr. Segal, Dr. Tsay has expanded his work to examine differences in both gene expression and lung microbiome markers in patients with and without cancer.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, the collaborators found that a dysbiotic lower airway signature they named pneumotypeSPT was more closely associated with patients with lung cancer than with patients who had benign nodules. A follow-up analysis showed that the microbiome and transcriptome signatures identified in the patients with cancer closely associated with pathways previously linked to lung carcinogenesis, supporting their potential as predictive biomarkers. In a separate study published in November in Cancer Discovery, which focused on a cohort of patients with lung cancer, Dr. Segal and Dr. Tsay found that the same biosignature was associated with increased mortality. In a mouse model of lung cancer, animals exposed to the human-derived bacteria likewise had worse outcomes than an unexposed control group.

As an extension of their work, the researchers are collecting samples from two distinct groups of patients with cancer. The first line of inquiry, funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), is focusing on how the microbial signature might influence the way in which patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer respond to immunotherapy such as PD-1 blockades or checkpoint inhibitors. “A number of studies have come out over the last few years looking at gut microbiome signatures that are associated with a response to immunotherapy,” Dr. Segal says, “but nobody has looked at the lung, and the lung–tumor interface is a very important one.”

Because some dysbiotic signatures are associated with a distinct immune status around and within the tumor, the researchers believe that the microbes or microbial products secreted into the lungs may influence the immunotherapy response. “If we know what microbes are present, what proteins and metabolites they’re producing, and which ones have immunomodulatory properties, it will help to understand why two different people respond very differently,” Dr. Segal says.

Lung microbiome samples are harder to obtain than stool or blood samples, but the NYU Langone team has the uncommon expertise needed to help identify the most relevant microbial drivers. “There are only a few centers in the country that do this,” Dr. Tsay says. That focus, he says, can help the researchers understand how the lung microbiome, specific microbial metabolites, local inflammation, and other factors alter the tumor microenvironment and the host immune response.

The researchers are additionally proposing to conduct longitudinal sampling of lower airway, stool, and blood samples before, during, and after immunotherapy to assess the interplay between the microbial communities and the host immune response. In addition, Dr. Segal says, the research may help identify microbial–host signatures that predict which subset of patients on immunotherapy will develop adverse autoimmune events such as pneumonitis.

Investigating Lung Cancer Recurrence and Molecular Pathways

For a second line of inquiry, now in its pilot phase, the researchers are collaborating with Harvey I. Pass, MD, the Stephen E. Banner Professor of Thoracic Oncology and chief of the Division of Thoracic Surgery at NYU Langone, to assess patients with early-stage lung cancer who are candidates for surgical resection. By scrutinizing the microbiome of the patients’ resected lung tissue, the investigators hope to identify microbial and host factors that predict cancer recurrence, which happens in roughly 30 percent of cases. To build on that research, the team is aiming for an NCI Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) grant that would support an expanded longitudinal study analyzing patients’ lung, blood, and stool samples for any correlative microbial and gene patterns.

Through a separate Chest Foundation Research Grant in Lung Cancer, Dr. Tsay is exploring how the lung microbiome may alter specific molecular pathways linked to lung cancer. Past research has suggested that microbial activation of pro-inflammatory inflammasome receptors can activate the IL-1 beta pathway, for example. Other evidence, in turn, has linked activation of the IL-1 beta pathway with an increased prevalence of lung cancer. “So we’re looking to see if there’s a connection among the inflammasomes, IL-1 beta, lung cancer, and the lung microbiome,” Dr. Tsay explains.

Beyond studying patient cohorts, the research team is developing in vitro airway epithelial tissue models and in vivo mouse models to tease out the associations. With a clearer cancer-linked biosignature, Dr. Tsay may be able to identify useful biomarkers as well. “Can we create a biomarker panel to help us with diagnosis or prognosis, or even with stratifying the risk of developing lung cancer?” he asks. If successful, the research may enable an even bolder push: to improve a patient’s clinical course by altering the microbiome.