Repairing a rare pulmonary disorder required cooling the patient’s body temperature to 68°F, stopping the heart, and removing arterial blockages in both lungs.

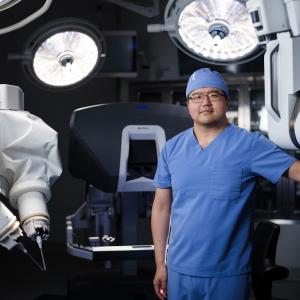

Credit: Derek Amengual

Erby Paul has always loved to run. As a boy in Haiti, he had played competitive soccer, and as a middle-aged dad in Brooklyn, he proudly outpaced his four children in footraces. But in 2013, at age 47, Paul began to feel short of breath during his daily six-mile circuit around Prospect Park. Although checkups, lab tests, and electrocardiograms found nothing amiss, his symptoms grew worse over the following years.

By his early 50s, Paul couldn’t climb a flight of stairs without feeling winded, and jogging was out of the question. His feet grew swollen, his lower legs ached, and he was constantly exhausted. “I told my doctor, ‘If you can’t find what’s wrong with me, I think I’m going to die,’” he recalls.

Paul, who works as a surgical technologist at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone, was referred to cardiologist Alan Shah, MD, a clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, in 2019. Dr. Shah ordered a stress echocardiogram, which examines the anatomy and physiology of heart function before and after exercise.

VIDEO: Erby Paul knew there was something wrong when he started to feel tired and was no longer able to run even a block in the park.

The test led to a sobering diagnosis: Paul had excessively high blood pressure in the lungs, or pulmonary hypertension. Dr. Shah explained that the progressive disorder makes the right side of the heart work harder to pump blood, eventually weakening the cardiac muscle. Untreated, it can lead to heart failure and be fatal. “That was a shocker,” says Paul. “I’ve always been active. I eat well, I don’t drink alcohol, and I don’t smoke.”

Despite healthy lifestyle choices, factors beyond a patient’s control—particularly genetics—can increase the risk of developing the disorder. There are five distinct classes of pulmonary hypertension, each with different causes, and several therapeutic approaches. To chart a path forward, Dr. Shah sent Paul to pulmonologist Roxana Sulica, MD, director of NYU Langone’s Pulmonary Hypertension Program. She is among a select group of physicians nationwide who specialize in treating the condition.

“At NYU Langone, we’re fortunate to have a multidisciplinary team with expertise in pulmonary hypertension—including pulmonologists, cardiologists, surgeons, radiologists, and nurses,” says Dr. Sulica. “That’s critical to helping patients with the condition live longer, healthier lives.”

Paul met with Dr. Sulica early in 2020. She ordered a series of tests, including a radioactive tracer to measure how well the air moves and blood flows through the lungs, called a VQ scan. They revealed that Paul had a rare form of the disorder caused by blood clots that form scar tissue in the pulmonary arteries and block blood flow.

While some forms of pulmonary hypertension can be managed with specific medications, the gold standard treatment for Paul’s condition, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), is a complex procedure requiring surgeons to slice open the affected arteries and remove the blockages. NYU Langone is among just a few hospitals with the surgical expertise to undertake the procedure, known as pulmonary thromboendarterectomy.

With the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily forcing the suspension of elective surgeries, Dr. Sulica put Paul on a blood thinner, a diuretic, and a medication that improves blood flow by dilating vessels. The drugs brought some relief to his symptoms, but his underlying condition continued to worsen.

Even once the suspension was lifted, Paul was hesitant to have surgery. Finally, in early 2022, Dr. Sulica introduced Paul to cardiothoracic surgeon Justin C. Chan, MD, who had recently joined her as co-director of NYU Langone’s CTEPH Program. Paul was reassured to learn that Dr. Chan had performed the procedure dozens of times with excellent outcomes.

“He took his time to explain every step, and he didn’t hide the risks,” Paul says. “Afterward, I said to my wife, ‘I’m ready.’”

The eight-hour operation took place on March 8, 2022. After placing Paul on anesthesia, Dr. Chan and a team that included Stephanie H. Chang, MD, surgical director of the Lung Transplantation Program, opened the sternum, connected him to a heart–lung machine, lowered his body temperature to 68°F to reduce the need for oxygen, and delivered medications to temporarily paralyze his heart. Then, they switched off the machine, stopping circulation completely—a state that can be safely maintained for a maximum of 20 minutes. Working rapidly but carefully, the surgeons removed scar tissue from arteries in the right lung first, restarting the machine briefly to avoid damage to the brain and other organs before moving on to the left lung. After clearing more than 20 arteries in total, they resumed circulation, returned the patient’s body temperature to normal, disconnected the bypass machine, and closed the chest.

Two days later, a physical therapist escorted Paul for a walk. To his delight, he was able to traverse much of the hallway at Kimmel Pavilion and even climb a small set of steps without discomfort. Paul was sent home the next week, and by the end of April, the now-58-year-old was back to running. “The speed is not what it used to be, but I hope to beat my kids again someday,” he says, with a laugh. “I can’t thank this team enough. They’re amazing.”

For Dr. Chan, the amazement is mutual. “Erby is such a strong, determined guy,” he says. “It’s fantastic to see him get his life back. That’s the reason we do what we do.”