NYU Langone Clinicians & Researchers Bring World-Class Expertise to the Challenges Facing Vulnerable Populations

NYU Langone experts treat children who experience trauma by examining various stressors that affect their mental health.

Photo: Juliana Thomas

As experts on the front lines of treating children who experience trauma in New York City, faculty from NYU Langone’s Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry are uniquely positioned to respond to a large-scale crisis that broadly impacts children’s mental health. In June 2018, such a crisis and response occurred when an influx of Central American children—most of them separated from their parents under the United States’ “zero tolerance” immigration policy—began to saturate the city’s refugee resettlement agencies.

“We asked these agencies, ‘What do you need?’” recalls Jennifer Havens, MD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, vice chair for clinical integration and mentoring, and director of child and adolescent behavioral health in NYC Health + Hospitals’ Office of Behavioral Health. “The answer was clear: They were trying to respond to a traumatic situation without a single child or adolescent psychiatrist on staff and urgently needed to fill that gap.”

In response, NYC Health + Hospitals sent Maria A. Baez, MD, clinical assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry and associate director of the child and adolescent mental health clinic at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue, to the East Harlem branch of Cayuga Centers. The branch was responsible for the daytime care of more than 200 migrant children who’d been placed in foster homes. A bilingual native of Colombia, Dr. Baez began performing psychiatric evaluations and providing psychotherapy for the children, consulting with Cayuga’s social workers and nurse practitioners.

Dr. Baez also facilitated the care of unaccompanied immigrant children referred by other foster agencies and of reunited families with pending asylum hearings at the outpatient Department of Child Psychiatry at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue.

Dr. Baez has been supporting children and parents with best practices and treatment modalities for a range of trauma-related presentations, including anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, suicidality, and self-injurious behaviors. “These children fled violence in their countries, endured dangerous journeys, and were then forcibly taken from their parents. Many children have to learn how to become children again after all of this trauma,” Dr. Baez explains. “While the focus of child psychiatrists, the news, and communities might shift away from this topic from time to time, the reality is that our help will be needed—likely and unfortunately—for a long time.”

Assessing the Impact of Child Separation Worldwide

Internationally known for his research on the impact of violence-related maternal stress on children’s mental health, Daniel S. Schechter, MD, the Barakett Associate Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and director of the stress, trauma, and resilience program, is working to expand NYU Langone’s capacity in related areas. “We’re taking a multidisciplinary approach that considers not only how trauma impacts development in terms of the individual child, but also how a family-focused mental health system can foster resilience,” he explains.

As an example, Dr. Schechter points to ongoing research by Chenyue Zhao, PhD, associate research scientist, who is investigating the effects of parent–child separation among children of Chinese migrant workers and immigrants. “In China, tens of millions of rural children are left behind with grandparents or other caregivers when their parents migrate to work in urban areas,” Dr. Zhao explains.

In a study published this year in the International Journal for Equity in Health, he and his team found that prolonged separation often seriously disrupts parent–child relationships among migrants’ children, especially among those facing additional adversities such as poverty; parental divorce; or frail, elderly caregivers. Dr. Zhao’s next study will assess emotional symptoms and behavioral challenges of immigrants’ children sent to live in China as babies and then brought back to the United States for the start of school.

Probing the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Stress and Adversity

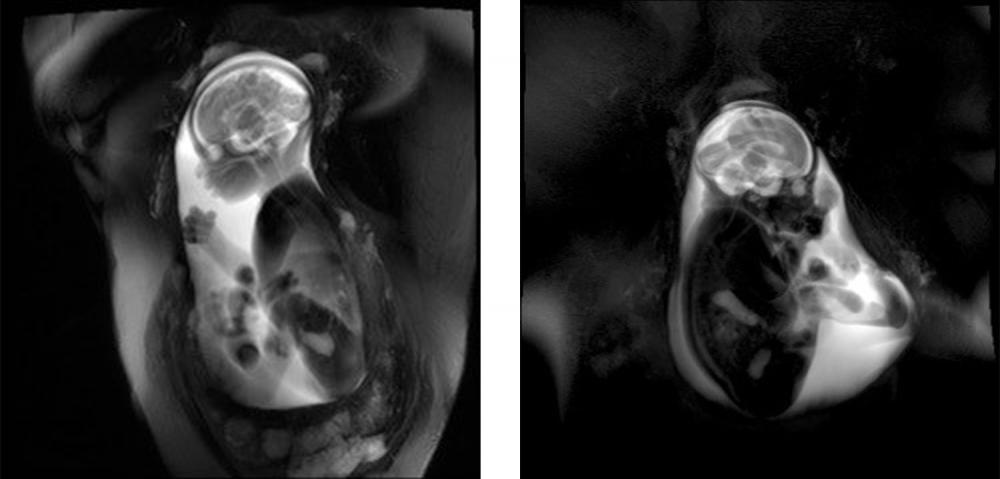

NYU Langone researchers are also exploring the impact of a mother’s trauma on her child’s brain development, both during pregnancy and into childhood. Moriah E. Thomason, PhD, a member of child and adolescent psychiatry and population health faculty, is leading research on developmental neuroscience and psychopathology from the fetal period across childhood and adolescence. Her research program focuses particularly on community cohorts, and on how trauma, health disparities, and psychosocial adversity interfere with healthy brain development. “We want to identify the risks associated with these dynamics and potentially develop new therapeutic inroads,” she explains.

At the 2018 meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, Dr. Thomason presented results from an imaging study showing a direct influence of maternal stress on fetal brain development. Using resting-state fMRI, she and her team examined functional connectivity in 47 fetuses scanned between the 30th and 37th weeks of gestation. Participating mothers were recruited from a low-resource urban area with high rates of community violence and other stressors; half were unpartnered, and many reported high levels of depression and anxiety. The researchers found that fetuses of mothers who were highly stressed showed reduced efficiency in total neural connectivity, most notably in the cerebellum and posterior cingulate gyrus.

Key to understanding the long-term impact of these brain changes, explains Dr. Thomason, is intense longitudinal follow-up. The mothers in the study are part of a cohort of 300 whom Dr. Thomason has followed for 7 years, and she will continue to track the group and their children. “We’re not just interested in these neuroscientific models of the developing brain,” she says. “We’re interested in who that child is going to become.”