Researchers at NYU Langone Health shed light on the effects of parental-related trauma and stress on the developing brain—beginning before birth.

Photo: Jm1366/Getty

Although many psychiatric and behavioral disorders are associated with trauma or chronic stress in early childhood, little is known about the neurobiological factors that may underlie such links. Researchers at NYU Langone Health are shedding light on how such experiences shape the developing brain—beginning before birth.

New Insights on the Prenatal Connectome

Moriah E. Thomason, PhD, the Barakett Associate Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and associate professor in the Department of Population Health, leads a wide-ranging research program on developmental neuroscience and psychopathology from the fetal period through adolescence. Among her primary concerns is how factors such as maternal stress and environmental exposures during pregnancy affect neural networks in the growing fetus. A pioneer in the use of resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) to examine functional connectivity in utero, Dr. Thomason has published more papers on the topic than any other investigator.

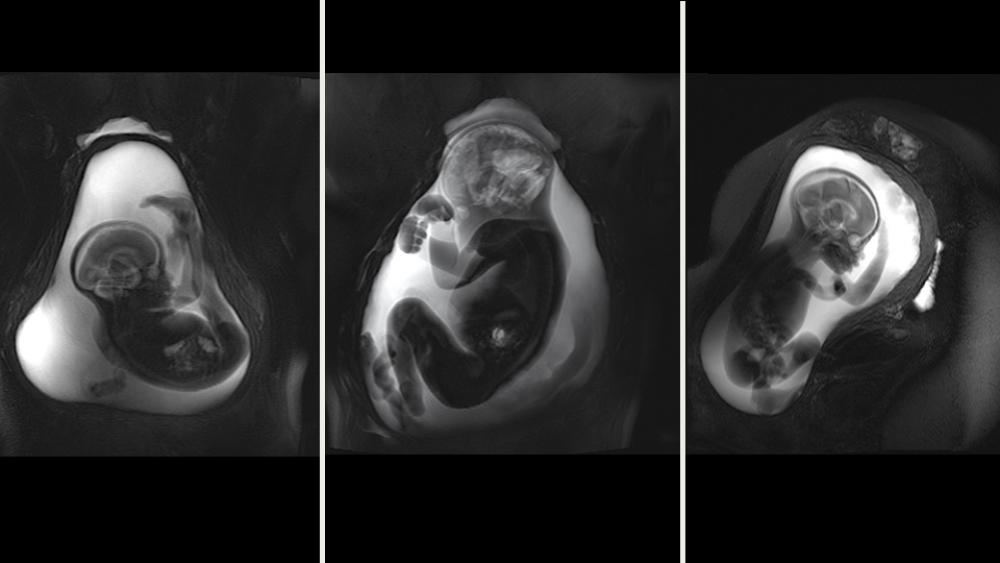

To fully understand how prenatal stressors affect the communication between brain regions, scientists need a baseline picture of the fetal connectome as a whole. In a study to be published in 2020 in the Journal of Neuroscience, Dr. Thomason and her team provide the first such portrait. Using novel fMRI techniques developed for this purpose, the group scanned the brains of 105 fetuses between 20.6 and 39.6 weeks gestational age. They then applied graph analytical methods to explore properties of small-world organization, modularity, and rich club hub organization of functional brain dynamics. Finally, they compared the average patterns of fetal and adult brain networks.

Across the 2nd and 3rd trimester, the fetuses’ connectome structure showed a robust degree of overlap with that of adults—61.66 percent. This connectional “blueprint” included four functional modules, compared with five in the adult group. As in adults, the fetal connectome showed a significant rich club organization in which central nodes communicate preferentially with one another, enhancing total network efficiency. “Although our emergent imaging methods are limited in their precision, these findings are truly striking,” observes Dr. Thomason. “They suggest that the basic layout of the connectome is established well before the brain begins interacting with the environment through sensory stimuli.”

In addition to offering clues to longstanding questions about the degree of functional maturity of the human brain at parturition, the study points to potential diagnostic or therapeutic applications for fetal fMRI. “Mapping the healthy fetal functional connectome may bring opportunities for early detection of functional alterations of the vulnerable developing brain,” Dr. Thomason explains. “Ultimately, we hope to learn how childhood developmental difficulties are influenced by known prenatal risk factors—such as maternal anxiety and depression, obesity, and substance abuse—with the goal of generating appropriate interventions.”

Mapping the Neurobiological Effects of Maternal Abuse

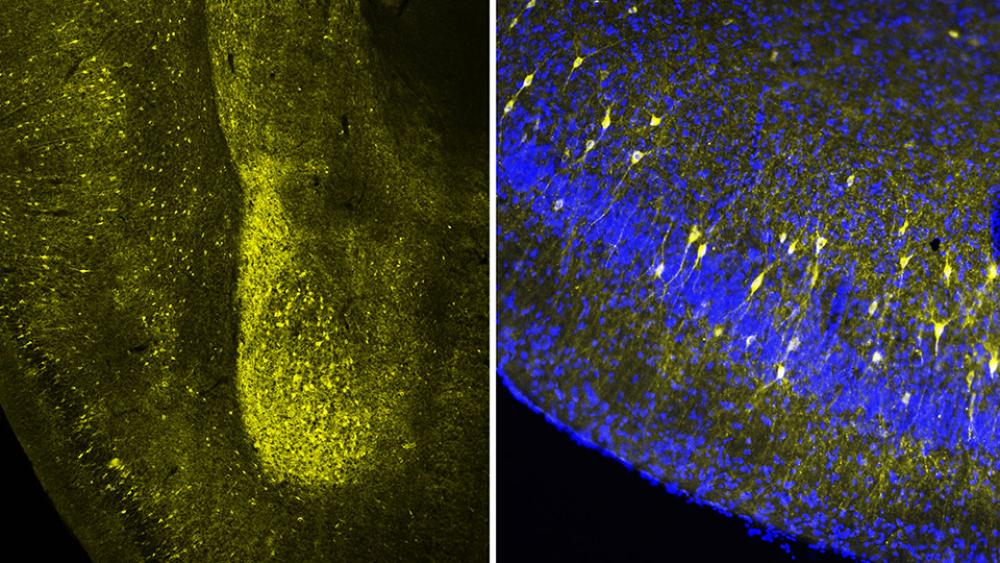

Regina M. Sullivan, PhD, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, is an internationally recognized expert on the neurobiology of infant attachment to the caregiver, as well as on the developmental impacts of childhood trauma when it is paired with the caregiver. In November 2019, using a rodent animal model, she and her colleagues published the first study showing how structures in the infant brain respond during the actual trauma inflicted by the parent and how associated stresses influence subsequent neurodevelopment and behavior.

Past studies in humans and animals have shown that the outcome of experiencing chronic maternal abuse can include shrinkage in an infant’s amygdala and hippocampus, as well as a broad array of behavioral deficits. In the new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, Dr. Sullivan and her co-authors set out to disentangle the causal factors behind these changes.

The team analyzed the brains and social behaviors of rat pups that had been subjected to five days of trauma. The pups experienced rough handling by their mothers from whom sufficient nesting materials to care for their offspring had been withheld. The results were then compared with those of pups given daily injections of stress-inducing corticosterone when left alone with a nurturing mother, an anesthetized mother showing no maternal behavior, or a rat-sized plastic tube.

The researchers found that the hippocampal shrinkage due to repeated trauma with the mother could be mimicked by repeatedly giving pups the stress-inducing drug even when the mother was anesthetized and even when she was not present. But to trigger such changes in the amygdala, as well as lasting behavioral deficits, required a social context of the mother while being given repeated doses of the stress-inducing drug, even if the mother was anesthetized. Pups given the drug in the presence of the plastic tube showed no changes in the amygdala or behavior. To further capitalize on animal models to show causal mechanisms, those behavioral effects could be blunted in both groups of pups by chemically blocking corticosterone action in the infant brain or by pharmacologically suppressing amygdala activity.

“Stress hormones have a beneficial role in brain development, but when levels are chronically elevated, it produces neurobehavioral deficits,” Dr. Sullivan explains. “Our findings suggest that repeated stress elevation associated with the mother or other primary caregiver targets a child’s amygdala, a brain area important for emotional processing.” These results are best understood within the context of the role of the parent as a regulator of a child’s emotions and a social buffer of stress. Parenting methods that permit exposure to life’s typical challenges alongside parental social buffering of stress help the child build a physiology that copes with stress.