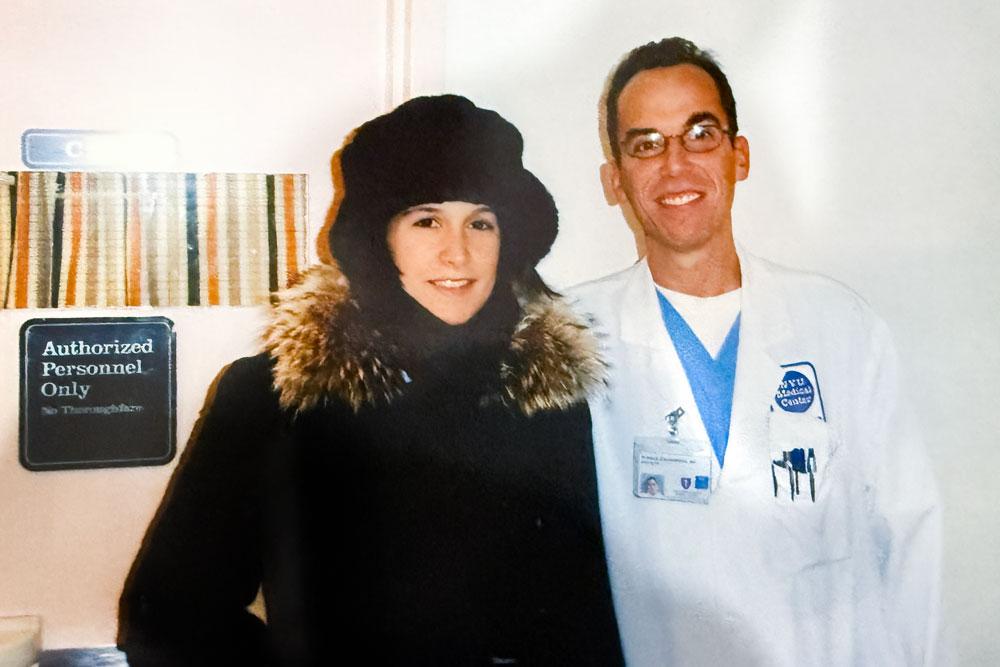

Courtesy: Jennifer Takos

Doctor Goldenberg?” The voice carried across Indiana University’s crowded move-in-day parking lot. Ronald Goldenberg, MD, a critical care specialist at NYU Langone Health, turned to find a face he hadn’t seen in over a decade but would never forget. There stood Jennifer Takos—vibrant, healthy, and moving her son into his freshman dorm. The same son whom Dr. Goldenberg had carried to the family car in an infant car seat 19 years earlier, after weeks of uncertainty about whether his mother would survive to raise him. The same dorm into which Dr. Goldenberg was moving his own son.

Out of 40,000 students on campus, somehow their boys had been randomly assigned as dormmates. It is the kind of coincidence that defies probability—much like Jennifer’s postpartum survival.

It was January 2005, and Jennifer Takos, then in her 20s and mother to a toddler daughter, had chosen to deliver her second child at NYU Langone. It was a decision that would save her life.

The cesarean delivery went smoothly. Baby John was healthy. Everything seemed routine until what should have been Jennifer’s final night in the hospital. “It can’t be put into words,” she recalls. “It’s the feeling that you can’t breathe.”

Walking the maternity ward’s halls, Jennifer felt her breathing become increasingly labored. Something kept telling her to keep moving, as if motion could somehow ward off the crisis building in her lungs. By the time she made it back to her room, she could barely draw breath. The last thing she remembers is looking up at medical staff swarming her bed.

Within hours, she was in full respiratory failure. Her lungs were filling with blood. That’s when Dr. Goldenberg, then a junior attending physician, stepped in.

“Dr. Goldenberg said he would save me. He told my father, ‘I’m going to save your daughter,’” Jennifer says, recalling what she’d been told later. The diagnosis would eventually prove to be a rare autoimmune condition, ANCA-positive vasculitis, triggered by childbirth.

What followed was a weekslong battle that showcased both the technical excellence and deeply human care that defines NYU Langone. While Jennifer fought for her life in the intensive care unit (ICU), the maternity ward staff created a nurturing cocoon for John, keeping him well beyond the usual discharge date. They filled her room with photos and notes: Mommy get better soon! Her husband went between the ICU and the nursery, maintaining the precious early bonds between mother and child.

“The team even found a way to save my ability to breastfeed,” says Jennifer, “since my husband told them how important that was to me—especially not being able to bond with my child in the way I expected in these early days.”

Dr. Goldenberg would arrive before dawn to check on Jennifer, let her know he was headed to the gym, and promise to return, creating a rhythm of reassurance that helped anchor her through the psychological turmoil of high-dose steroids and critical illness. “He was just above and beyond in every way,” Jennifer says.

After nearly three weeks, Jennifer was stable enough to go home. In a moment that has become family lore, Dr. Goldenberg carried John to the car himself. But the medical journey was far from over.

“I didn’t have a typical maternity period,” said Jennifer. “I was still building my strength back emotionally and physically, and I feel really fortunate that my husband and my parents were able to help care for me, my toddler, and my infant. That support was an extension of what I got in the hospital and was so necessary to me being able to find my way back to myself so I could be the mom I needed to be.”

Jennifer would face several relapses of her condition over the following years. Each time, the team at NYU Langone was there, with Dr. Goldenberg coordinating her inpatient care and Doreen J. Addrizzo-Harris, MD, managing her ongoing treatment.

“I have the two best doctors that ever existed, I think,” Jennifer says. The collaborative approach between ICU and outpatient care helped her navigate both acute crises and long-term management. Today, she lives a full, active life in Pittsburgh, running restaurants with her husband and following her son’s hockey career—all while maintaining the medication regimen that keeps her condition in check.

The chance meeting at Indiana University felt like more than coincidence to Jennifer. “It made me feel like everything was meant to be,” she says. “It was a sign that my son is in the right place.”

For Dr. Goldenberg, it was a rare glimpse at the full arc of critical care medicine—seeing not just a patient saved, but a life fully lived. It represented something essential about medicine at its best: not just the technical excellence to save a life in crisis, but the commitment to see that life through to its next chapter.

The evening after their parking lot reunion, the families ran into each other again at a local restaurant—another piece of destiny, it seemed, in a story full of them. They took photos together, Jennifer and Dr. Goldenberg with their college freshman sons, photos that now stand alongside old Polaroids from those harrowing weeks in 2005.

Every winter for 19 years, Jennifer’s father has sent Dr. Goldenberg a box of chocolates, marking the anniversary of his daughter’s survival. It’s a sweet reminder of a promise kept, of a young mother who lived to raise her children, of medicine practiced with both skill and heart.

Media Inquiries

Arielle Sklar

Phone: 646-960-2696

Arielle.Sklar@NYULangone.org