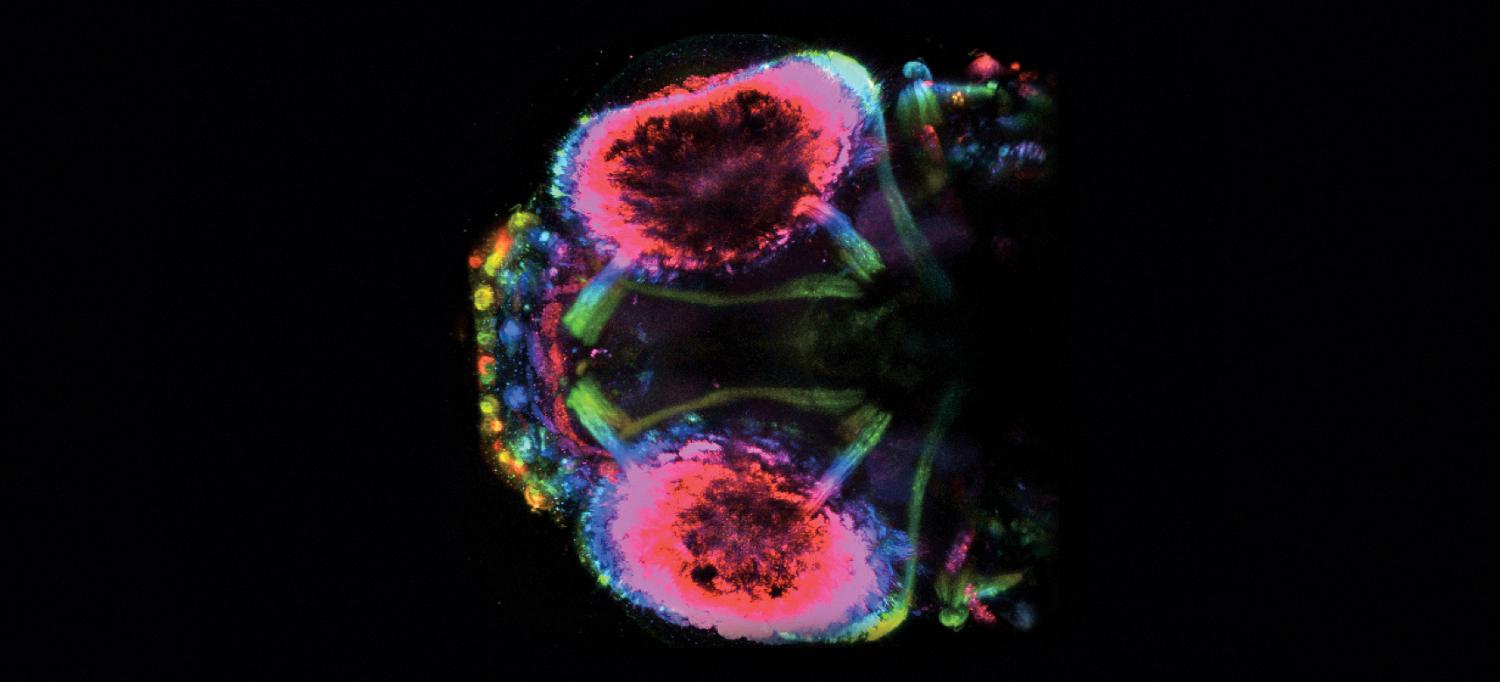

Image: Courtesy of Schoppik Lab

As an integrated academic medical center, we don’t just treat conditions—we look for their origins, often in unexpected places. Take dizziness, one of the most common reasons people seek out medical help. Vertigo, or the false sensation that you are spinning, can result from something as benign as standing up too abruptly or from something much more serious, such as a tumor or stroke. The multitude of possibilities can make it challenging to arrive at a correct diagnosis.

To gain a better understanding of how the brain keeps us balanced and what goes wrong when it doesn’t, David Schoppik, PhD, assistant professor of otolaryngology and neuroscience and physiology, studies the brain structure of the diminutive tropical zebrafish, seen here beneath a fluorescent microscope. The zebrafish uses a neural architecture remarkably similar to ours to maintain balance—just one reason it’s among the most studied organisms in science.

In one recent study, Dr. Schoppik and his team measured the ability of larval zebrafish to stabilize their gaze following body rotations, and identified the neurons responsible for this important reflex. “Our goal,” he says, “is to leverage the simplicity and molecular control of the fish model to understand and ultimately treat disease.”