Prognosis Transformed for Patient with Cavernous Malformation Considered Unresectable

Guided by neurosurgical expertise and advanced surgical planning enabled by state-of-the-art imaging, a team led by Dr. Howard A. Riina executes the carefully planned resection of a deep-seated cavernous malformation.

Photo: Keiji Drysdale

When other, less invasive measures failed to contain an aggressive, deep-seated cavernous malformation, a patient with worsening neurological complications sought the expertise of NYU Langone neurosurgeons with experience in successfully removing such high-risk lesions. Aided by advanced imaging and a high degree of surgical skill, a multidisciplinary team carefully planned and executed the safe resection of the lesion, which others had considered inoperable—preserving the patient’s function and transforming his prognosis.

Weighing the Risks of a Complex Resection

The patient, a 38-year-old male, had been diagnosed with the cavernous malformation in 2004 after presenting with acute hemorrhage in his right basal ganglia. Over time, the lesion grew larger and began to compromise the patient’s function, causing sensory loss and left-side deterioration that impacted his gait and upper extremity strength. A repeat MRI performed at NYU Langone in 2019 revealed what had become a very large cavernoma in the thalamus with associated hemorrhage.

In the 15 years since his diagnosis, the patient had sought treatment at other institutions. With watchful waiting as the primary recommended management approach, the patient had a shunt placed in 2010 when he developed obstructive hydrocephalus, and Gamma Knife® radiosurgery was performed to prevent recurrent bleeding. Surgery to remove the lesion had been deemed too risky due to the location of the malformation in the thalamus, with an increased risk for postoperative hemiplegia due to the lesion’s anticipated close proximity to the corticospinal tract and other critical structures. However, Howard A. Riina, MD, professor in the Departments of Neurosurgery, Radiology, and Neurology, and director of the Center for Stroke and Neurovascular Diseases, saw surgery as the only option and charted a path toward a safe resection with the multidisciplinary expertise in place at NYU Langone.

“These lesions are typically much smaller, but this one was upwards of 8 cm, compromising a significant portion of the patient’s brain—meaning he was already hemiparetic from the lesion itself despite the outside interventions he received,” notes Dr. Riina. “So the question was, could we get this out and preserve most of his function. We felt we had the right team in place to safely achieve that delicate balance.”

Division of Labor Informs Comprehensive Surgical Plan

The procedure—a right frontal craniotomy, shunt removal, and resection of the cavernous malformation—required a “tumor mentality” to remove the vascular lesion. “Cavernous malformations can grow like a neoplasm, destroying the brain’s structures as they increase in size and bleed,” explains Dr. Riina. “So the approach itself was just as important as the lesion’s removal, in order to preserve healthy tissue.”

“This is not a procedure where you look at an image and say right away, ‘I’m going to perform the operation this way.’ It’s about creating an initial plan, then adding layers of imaging, and revisiting your thought process. Only then do the team and the plan start to come together.”—Howard A. Riina, MD

For that reason, the surgical team included John G. Golfinos, MD, the Joseph Ransohoff Professor of Neurosurgery and chair of the Department of Neurosurgery, who would complement Dr. Riina’s vascular expertise and perform the delicate approach. Careful, coordinated surgical planning would utilize NYU Langone’s most advanced technical capabilities, imaging modalities, and multidisciplinary talent to achieve the best possible outcome. “This is not a procedure where you look at an image and say right away, ‘I’m going to perform the operation this way,’” notes Dr. Riina. “It’s about creating an initial plan, then adding layers of imaging, and revisiting your thought process. Only then do the team and the plan start to come together.”

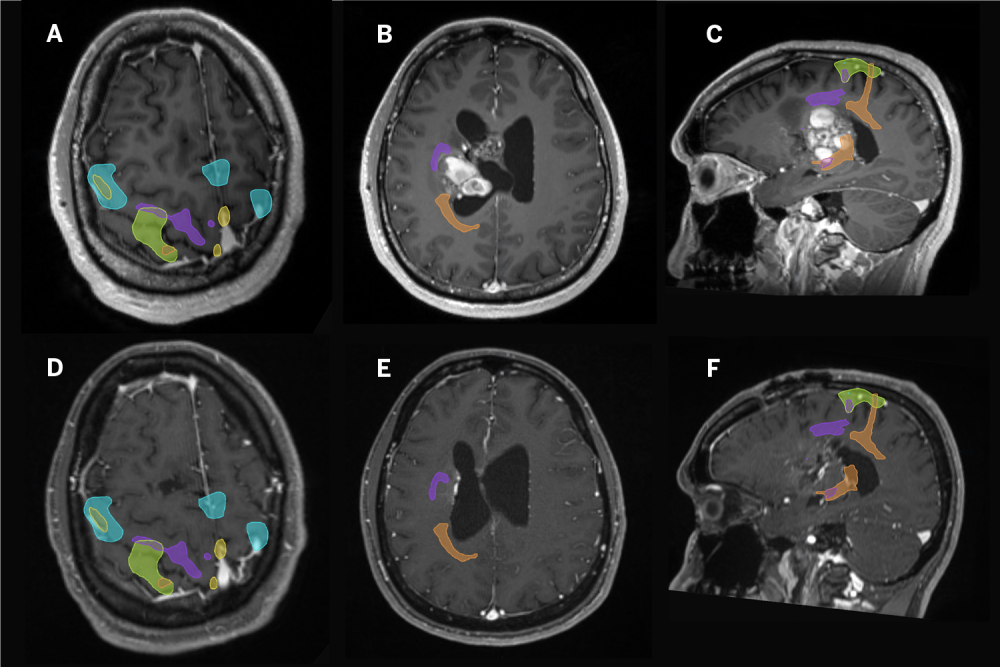

Functional MRI combined with advanced tractography would define the proximity of the lesion to the brain’s eloquent cortex and white matter pathways to identify a safe anatomical corridor to reach and then resect the deep-seated lesion.

“Before you reach the lesion, you have to traverse or avoid several brain anatomy structures that control movement, coordination, sensation, and potentially language—so my role was to guide Dr. Golfinos and Dr. Riina to a safe window toward a lesion perilously close to the corticospinal tract,” explains Timothy M. Shepherd, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Radiology and director of brain mapping. “The functional MRI and tractography provide maps of key brain anatomical structures, information that must then be interpreted and applied correctly by experienced surgeons.”

Every Cell Resected, Through Careful Execution

With the carefully crafted plan in place, Dr. Golfinos began the surgical approach, using image guidance to reopen the patient’s right frontal incision, performing a right frontal craniotomy and removing the previously placed shunt catheter.

Dr. Riina then moved in toward the lesion, using the BrainLab system to map the contours of the tumor. He performed initial dissection and removed residual evidence of prior hemorrhage. With the gross resection complete, the perimeter of the cavity was again mapped using intraoperative MRI to ensure no residual malformation remained. “You have to make sure you’ve gone deep enough and removed the entire lesion because if you leave even one cell behind, it will come back,” explains Dr. Riina.

When a small, deep residual portion of the cavernous malformation was identified on the intraoperative MRI, the resection continued and the lesion was further resected using residual as a new image guidance target from the updated MRI, projected into the operating microscope. When complete resection was confirmed, the dura and wound were closed, and the patient was taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) in stable condition, able to follow commands and move his right side with normal power. The patient recovered well and maintains his preoperative leg and arm movement—function he would have lost without intervention.

“This lesion was allowed to grow uninhibited for far too long—nearly 20 years—and eventually it would have killed this patient,” says Dr. Riina. “Despite the risks, we knew we had to take it out, not only to preserve function but to save his life. And fortunately, here at NYU Langone, we had the right team and technology to give him the best possible outcome.”