A Plastic Surgeon & a Tissue Engineer Transform Reconstructive Procedures Thanks to Affordable Three-Dimensional Surgical Models

During his long career as a plastic surgeon, Roberto L. Flores, MD, has reconstructed more than 40 ears—some for children born without them, others for people who have lost ears to trauma or disease. The procedure, commonly performed in two stages, is considered one of the most challenging in the field. Surprisingly, the part surgeons find most formidable has nothing to do with surgery, Dr. Flores says. Rather, it’s the artful, painstaking sculpture required to transform cartilage carved from the patient’s rib cage into the intricate shape of an ear.

“We all know what an ear looks like, but try to reproduce it,” notes Dr. Flores, the Joseph G. McCarthy Associate Professor of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery in the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery at NYU Langone. “We’re using true artist techniques that can take a lifetime to perfect.”

Surgeons whittle strips of cartilage using only a crude outline of the patient’s healthy ear as a guide. Last year, feeling frustrated about the rudimentary reproduction one of these drawings offered, Dr. Flores thought of a better way. He was already collaborating with tissue engineers at NYU College of Dentistry on a federally funded project to create three-dimensional (3D)–printed bone replacements to help heal skull and jaw defects in children. Why not use those same resources to print 3D replicas of patients’ ears as visual guides, he thought.

It seemed like such a commonsense idea, but when Dr. Flores combed the scientific literature for information about 3D surgical models for ear reconstructions, he found nothing. “It was so hard to believe that in 2018, a pencil drawing would be standard-of-care practice for one of the most difficult technical procedures in plastic surgery,” he says. One barrier, he realized, was the expense of 3D printing.

If outsourced to a commercial printer, such models could cost up to $3,000. “It would come out of the patient’s pocket one way or another,” he notes. An additional challenge was the time and expertise required to generate and manipulate the digital models, and then sterilize them for the procedure.

For Dr. Flores, it was a matter of tapping his friend and colleague, tissue engineer Paulo G. Coelho, DDS, PhD, whose expansive team of researchers possessed all the necessary hardware and skills to print the models on demand. “It’s actually very easy for us,” says Dr. Coelho, the Leonard I. Linkow Professor of Biomaterials and Biomimetics at NYU College of Dentistry and professor in the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery. The only real expense would be the “ink,” a sugar-like filament also used in dissolvable stitches. Total cost per ear: less than a dollar.

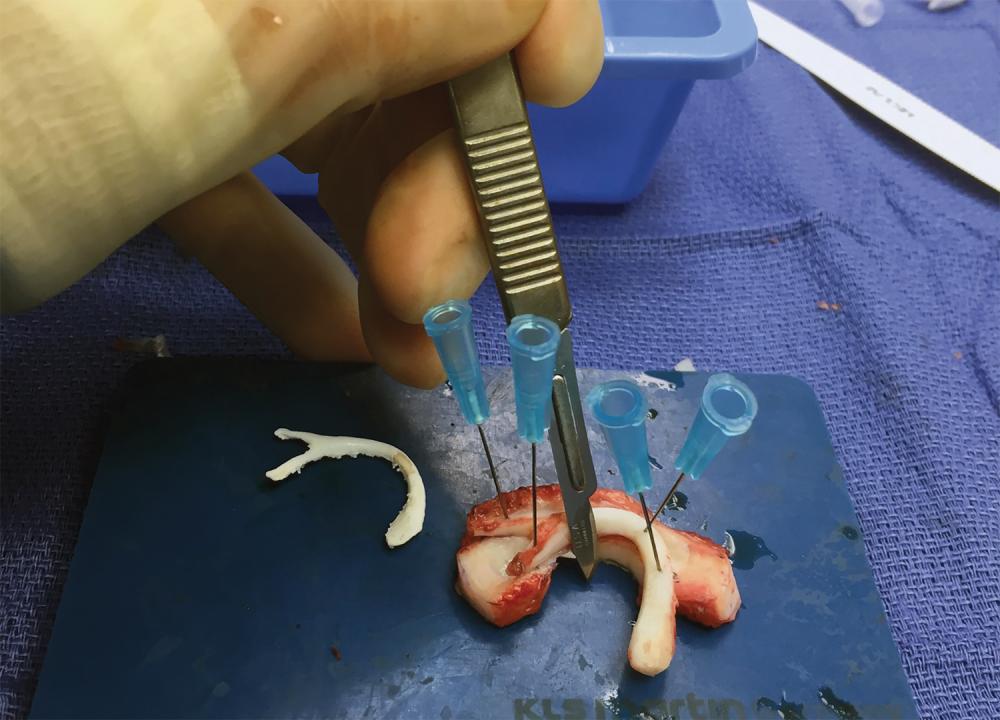

Since they began collaborating over a year ago, Dr. Flores has used 3D–printed models for several ear reconstructions, including a recent case in which the patient’s ear was mauled by a dog. “The 3D models reveal the complicated contours of the ear so much better than the drawings,” says Dr. Flores. “They eliminate much of the guesswork that goes into the reconstruction, and ultimately result in more efficient and precise outcomes.”

For Dr. Coelho’s part, his team can produce models within 24 hours. They upload a 3D photograph of the patient’s unaffected ear, and then use software to create digital templates of the five different cartilage structures Dr. Flores will model during the surgery. The printing and sterilization process can take 14 hours, but most of it is automated. “You can press print and walk away,” notes Dr. Coelho.

The models have been so successful that Dr. Flores has begun using them in his cosmetic surgery practice, both as visual references during surgery and as props during patient consults. “With a model of the patient’s nose, you can say, ‘This is our goal,’” Dr. Flores says. “And the patient can say, ‘I like that’ or ‘I don’t like this.’”

Dr. Flores is eager to share his knowledge of 3D printing and the collaboration that made it possible. He’s presented his technique at conferences nationwide and published two papers about it in peer-reviewed journals. “I predict that 3D printing will change the way plastic surgery of the face is performed,” he says. “My message is that it’s not about the technology. It’s about bringing together the right kind of people.”