NYU Langone’s multidisciplinary team of experts collaborate on a complex spinal reconstruction.

Photo: Juliana Thomas

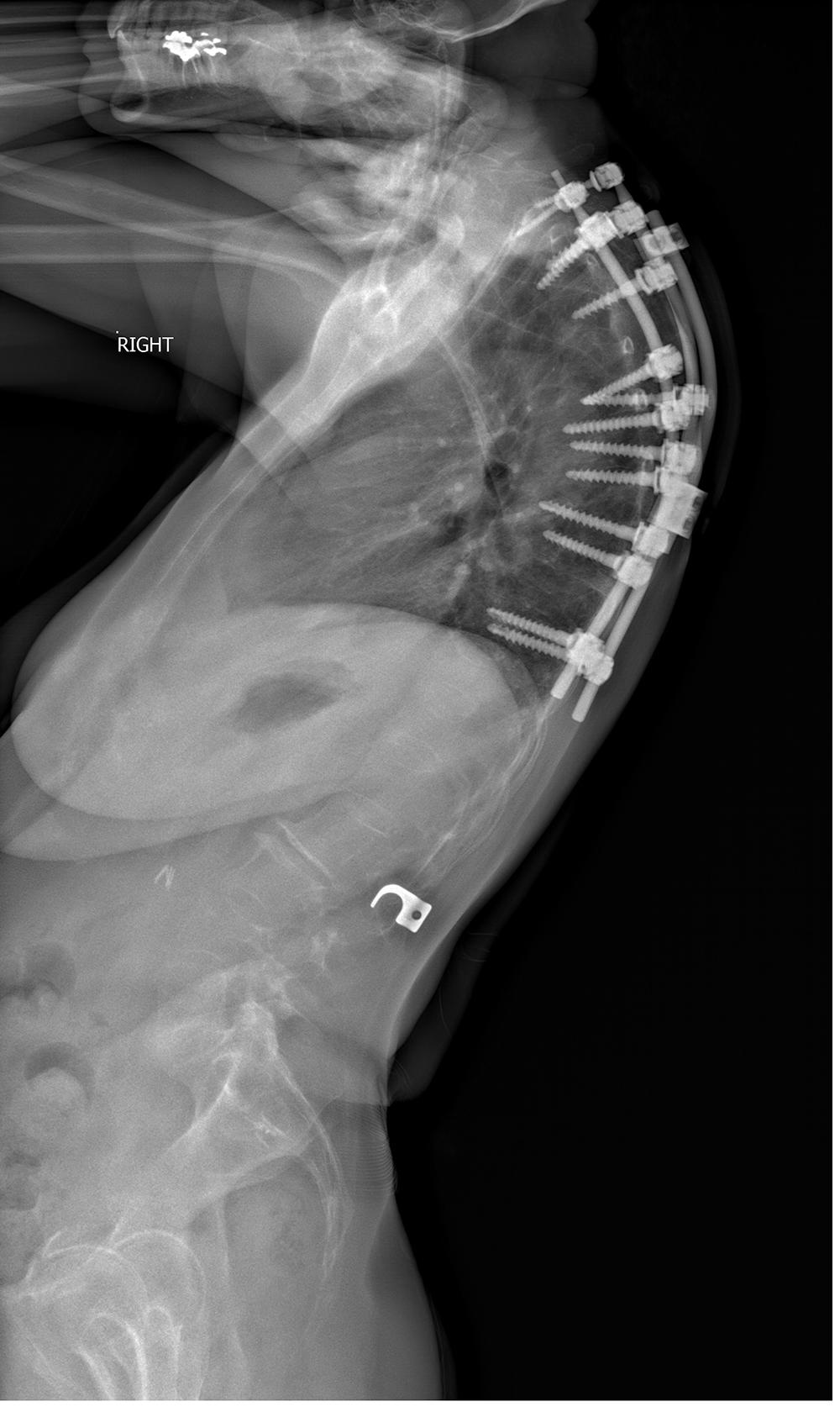

When a patient with a history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis developed proximal junctional kyphosis as a result of previous surgery, she turned to experts at NYU Langone’s Spine Center for surgical consultation.

With a history of collaboration in complex spinal reconstructions, a multidisciplinary team of experts from the Department of Neurosurgery and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery took an innovative approach to correct her long-standing deformity with a radical surgical solution.

Redesigning the Spine to Correct a Long-Standing Deformity

A 57-year-old woman with a long, complex history of spinal deformity and surgery presented with worsening head drop, neck and upper back pain, numbness, and loss of horizontal gaze. She had undergone Harrington rod placement for scoliosis as an adolescent, later developing proximal junctional kyphosis at T5.

Although some improvement was initially achieved with a pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO) at T4 with posterior spinal fusion from T1 to T10, subsequent progression of recurrent C7-T1 kyphosis had resulted in severe pain and functional disability.

The patient’s major structural problems demanded far more than a traditional PSO, typically done at C7. “The geometry of this bone limits any potential correction,” explains Themistocles Protopsaltis, MD, associate professor of orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. “This patient needed part of the bone removed, the vertebral column resected, and her head repositioned since her chin had fallen to her chest—and we were able to draw on our extensive body of research to meticulously plan the perfect alignment.”

A T2 vertebrectomy with dorsal placement of an expandable cage was identified as the safest approach to correct the deformity. This nontraditional strategy would help to circumvent the risks of paralysis from spinal cord injury and hand weakness from C8 nerve injury.

“With this approach, we could reduce the potential for a disabling neurological injury, while increasing the space available for us to fully correct the spinal alignment,” says Michael L. Smith, MD, assistant professor of neurosurgery.

Careful Planning and Close Collaboration Guide Finely Tuned Spinal Realignment

The surgical plan was essentially to reconstruct the patient’s failing spine architecture by disconnecting and then reconnecting her cervicothoracic spine. To begin, the patient was placed in the prone position on the operating table, and the vertebral column was exposed, including the previously placed spine instrumentation.

After removal of the rods, previously placed pedicle screws were replaced from T1 to T10 to achieve good purchase, and new screws were placed from C2 to C7. A wide laminectomy was performed, with careful dissection of scar tissue from the dura to expose the thecal sac.

Circumferential decompression of the spinal cord allowed visualization of any spinal nerve impingement prior to performing the correction. “Our goal was to ensure that at the critical moment when we did the alignment correction, there would not be any compression that could put the spinal cord at risk,” notes Dr. Smith.

Temporary stabilizing rods were placed, and the transverse processes were removed before resection of the posterior lateral bony elements and bilateral T2 pedicles. Careful dissection around the T2 vertebral body to the ventral midline was achieved without injury to the soft tissue structures and the great vessels.

The vertebrectomy was performed from inferior T1 to the superior T3 endplates, the epidural plane was opened, and the posterior longitudinal ligaments were tamped into the defect. A titanium expandable cage was placed and packed with bone graft harvested from the iliac crest.

To close the osteotomy, the Mayfield head holder was released and repositioned while spinal instrumentation was used simultaneously to apply correction forces. These maneuvers placed the patient’s cervicothoracic spine into ideal alignment. A five-rod construct was placed across the vertebrectomy with fixation spanning T10 to C2, including C2 pedicle and laminar screws and thoracic pedicle screws.

Intraoperative imaging confirmed adequate reconstruction before arthrodesis was performed from C2 to T3. There were no changes in intraoperative neuromonitoring, with motor function confirmed before the patient was extubated and transferred to recovery.

“By taking the correction down to a lower level, we were able to achieve the radical correction needed to address this patient’s profound deformity,” Dr. Protopsaltis explains. “With our detailed preoperative planning, we attained the necessary deformity correction and the anterior column lengthening using a high-grade osteotomy and the expandable device.”

Shared Experience Reduces Operative Risk to Correct Complex Deformity

Vertebral column resection is a long and challenging surgical procedure, and the extraordinary complexity of this particular case required a critical combination of expertise, planning, and collaboration in executing the plan.

The deformity corrected, the patient now walks with normal alignment and is able to look left and right with a more typical horizontal gaze and without any loss of neurological function.

“In the case of a major spinal deformity and an alignment loss like this one, there are no intermediate options—a technically challenging reconstruction drawing upon our shared experience was needed to get her standing upright again,” says Dr. Smith. “Fortunately, our expertise and experience enabled us to provide her with a definitive solution.”