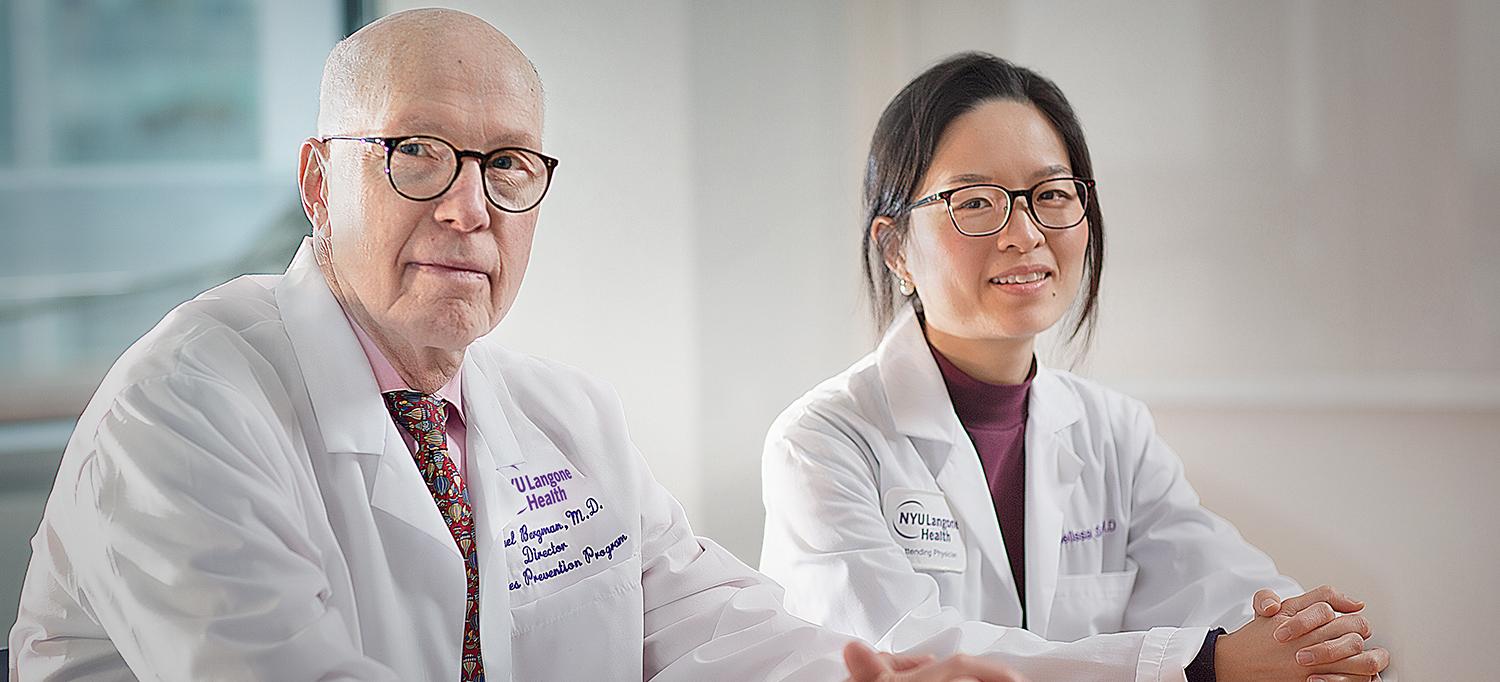

Endocrinologists Dr. Michael Bergman and Dr. Melissa Sum and colleagues are studying whether continuous glucose monitors can provide a convenient, sensitive, and less invasive approach for early detection of diabetes.

Photo: NYU Langone Staff

A study led by investigators at NYU Langone Health is finding that a commercially available continuous glucose monitor (CGM)—the type currently used by hundreds of thousands of patients with diabetes—may hold promise for preventing type 2 diabetes before it develops by detecting glucose abnormalities that typically fly under the radar.

A Window of Opportunity to Delay or Reverse Glucose Tolerance

The majority of the approximately 84 million people in the United States who have prediabetes are unaware of their condition—even though, based on epidemiological evidence, about 70 to 90 percent of them will develop diabetes over the course of 6 to 8 years.

Michael Bergman, MD, clinical professor in the Departments of Medicine and Population Health, director of NYU Langone’s Diabetes Prevention Program, and section chief of endocrinology at the VA NY Harbor Healthcare System’s Manhattan campus, and his colleagues are investigating the use of the CGM in high-risk individuals to detect subtle glucose abnormalities (when individuals do not have any symptoms) considerably earlier than current testing methods allow.

None of the three currently used conventional methods of measuring glucose—based on the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—is optimal for detecting early changes. Fasting blood glucose only provides a limited estimate of how the body is handling sugar, but even a normal reading may overlook individuals with abnormalities in the nonfasting state, thus underestimating the severity of underlying glucose disorders.

Hemoglobin A1c testing, which can be performed without fasting, reflects average blood sugar level over the prior two to three months but is insensitive and can be affected by a variety of conditions. As many as 25 percent of individuals who have a normal hemoglobin A1c (below 5.7 percent) may, in fact, have glucose abnormalities. Finally, the two-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), the gold standard for detecting glucose abnormalities, is cumbersome, costly, and inconvenient.

If the promising data bear out, the CGM could fundamentally change how doctors identify and treat glucose disorders in high-risk individuals. Identifying an effective and practical method for early screening would allow physicians to take advantage of a window of opportunity to prevent or reverse changes in glucose tolerance at an earlier stage.

Repurposing an Existing Technology to Improve Screening

A small, painless device the size of a quarter, the Abbott FreeStyle Libre CGM is inserted in the back of the arm and measures tissue glucose levels every 15 minutes throughout a 24-hour period. As a method that may be more sensitive, more convenient, less invasive, and work-intensive than the OGTT, investigators theorize the CGM may be able to detect subtle changes in glucose abnormalities years earlier than the manner in which prediabetes is detected currently.

“We want to compare glucose levels determined by a CGM with those measured by an OGTT and see how they correlate,” says Dr. Bergman, the principal investigator of studies testing CGM for early detection. “Our hypothesis is that a CGM would promote more accessible and reliable screening with a simplified approach.”

Dr. Bergman and his associates also want to test how often individuals with normal A1c actually have glucose abnormalities. “Our hypothesis is that it occurs more often in individuals at high-risk for diabetes than we are aware of,” he says.

Compelling Preliminary Data on Outpatients, with Inpatient Study Coming

At the Clinical Research Center at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue, researchers have reached the halfway point of a pilot study of the CGM as an early screening device in outpatients who have one or more risk factors, including family history of diabetes, obesity, or high triglyceride levels. Individuals with a normal A1c have the CGM implanted and return for an OGTT within a few days while still wearing the device.

“We’ve now tested approximately 10 individuals and, virtually in every case, a very strong correlation between the OGTT and CGM results has been demonstrated,” Dr. Bergman says. He and his team expect to collect data from about 30 high-risk subjects by mid-2020.

The same investigator group is also in the planning phase of a similar study with inpatients. Patients with acute coronary syndrome admitted to the Manhattan campus of the VA NY Harbor Healthcare System—25 to 40 percent of whom may have unrecognized blood glucose abnormalities and therefore are at higher risk for poor cardiac outcomes—will be enrolled.

Prediabetes occurs insidiously over a 12- to 14-year period, from the smallest detectable change in glucose tolerance until frank diabetes occurs. Typically, physicians identify prediabetic changes only three to six years before the onset of diabetes. Intervening at an earlier point in the process—perhaps 8, 10, or 12 years in advance—allows more time for recommended lifestyle modifications. This may reduce the risk for developing diabetes beyond what has been documented to date.

Individuals with prediabetes defined by current criteria can experience a 40 to 70 percent reduction in diabetes risk. However, this benefit is often not sustained over a 10- to 20-year follow-up period (Tabák et al., 2012, Lancet), perhaps reflecting late intervention in the lengthy trajectory to diabetes. Earlier intervention utilizing more sensitive criteria may eventually reduce the risk of complications and improve health outcomes and quality of life. This requires further study, however.

“So far, the data look very compelling, and if the results remain consistent, the use of the CGM would be a much simpler and practical approach to screening for glucose disorders than asking patients to undergo the OGTT in a clinical laboratory,” Dr. Bergman says. “I think it would promote more reliable screening than what is done currently.”

Team members involved in these studies include Melissa Sum, MD; Binita Shah, MD; Brenda Dorcely, MD; David Carruthers, MD; and Anjana Divakaran, MD. The outpatient study is supported through grants from the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) and the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism. Abbott FreeFtyle Libre Pro sensors are being generously provided by Abbott Diabetes Care.