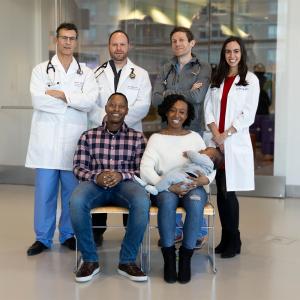

Doctors Dan Halpern, MD, director of Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, and Ralph Mosca, MD, chief of Pediatric and Adult Congenital Cardiac Surgery, with patient Jeanne Colon.

Photo: Ben Baker

Jeanne Colon was 34 years old when she landed at NYU Langone Hospital—Brooklyn, but she felt like someone at least twice her age.

She couldn’t climb a flight of stairs or walk her first-grader to school without getting severely winded. Her chest ached constantly, and she sometimes passed out if she pushed herself too hard. She woke up with a choking sensation several times a night. Although she often vomited after eating, her already hefty 5-foot frame had ballooned with fluid retention to 225 pounds. She’d recently had to give up her job as a city maintenance worker and go on disability.

The single mother of two boys, Colon had known for more than a decade that something was wrong with her heart, but she’d never learned exactly what it was. In 2001, after her older son had to be delivered by emergency cesarean delivery due to oxygen deprivation, doctors at another New York hospital had found evidence that she had a congenital cardiac defect. Afraid to face the potential repercussions, she’d left without probing further.

Then, in 2005, she was hospitalized after a miscarriage, and her own blood oxygen dropped so low that her skin took on a bluish tint—a condition known as cyanosis. To find the cause, clinicians performed a transthoracic echocardiogram, placing an ultrasound probe on her chest to obtain images of her heart. Colon’s obesity, however, made it difficult to get a clear picture. A coronary angiogram, in which a dye visible in X-rays is injected into coronary arteries to show blood flow, was ambiguous as well.

Doctors then proposed a more invasive test: a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), in which an ultrasound probe is inserted down the patient’s throat to take a close-up of the beating heart. Because the procedure was to be performed under moderate sedation, which could worsen the deficiency in the amount of oxygen reaching her tissues, it was put on hold until Colon’s oxygen levels recovered. No one could say how long that would take, though, and after a few days, she signed out of the hospital again.

“At that point, I didn’t actually feel sick,” she explains. “My heart had always raced when I was stressed out or upset, and my lips would turn purple at times, but nobody told me it was something to worry about. I thought, ‘What’s the point of going through all this hassle?’” Colon had another reason to avoid sticking around: Having lost her mother to cancer as a teenager, she associated hospitals with suffering and death. Just being inside one made her anxious, and the thought of surgery terrified her. “My mom died after her second operation. I was, like, ‘I don’t want it.’”

Colon’s condition soon began to deteriorate. In 2008, when she was hospitalized for a mouth abscess, she was found to be cyanotic again. This time, she underwent a TEE and was diagnosed with an atrial septal defect—a hole in the wall between the atria, or upper chambers, of the heart.

That didn’t solve the puzzle, however. Although atrial septal defects commonly trigger many of the symptoms Colon was suffering, and can sometimes be repaired by simply patching the hole, cyanosis seldom occurs unless there is associated pulmonary disease or a problem elsewhere in the circulatory system. Such complicating factors can be challenging to uncover and difficult to treat. But once more, Colon fled before the investigation was complete.

By early 2015, she was too ill to delay any longer. She brought what medical records she could find to a hospital near her home in Harlem, but was told that her condition was too complex to be handled there. An aunt in Brooklyn offered to take her to NYU Langone Hospital—Brooklyn (then known as Lutheran Medical Center), where Colon herself had been born and whose recent merger with NYU Langone had brought it vast new clinical resources.

That August, Colon and her aunt met with Thao Ngo, MD, clinical instructor of medicine and director of noninvasive cardiology. Because the cardiovascular effects of atrial septal defects may change over time, and Colon’s earlier imaging results were unavailable, Dr. Ngo ordered yet another set of tests.

As before, the electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were inconclusive, though they seemed to indicate a weakness in the left side of the heart. Another TEE was ordered, but it, too, had to be postponed. On the appointed morning, Colon’s cyanosis was so severe that she was admitted to the cardiac care unit and put on oxygen. After three days, her blood saturation remained subnormal—a clear sign that this was more than a simple atrial septal defect.

Dr. Ngo knew it was time to bring in specialized help. She had just attended a talk by Dan G. Halpern, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program at NYU Langone. “I was impressed not only by his expertise and judgment, but by his kindness and humility,” she remembers. “It was clear that he cared deeply about his patients.” She called Dr. Halpern, who agreed to take on Colon’s case.

In recent decades, pediatric cardiologists and cardiac surgeons have made remarkable strides in saving children with congenital heart disease, even those with severe abnormalities such as missing valves and misdirected coronary arteries. Of the 1 percent of infants born with heart defects, more than 90 percent now survive to adulthood. But many such defects go undiagnosed for years—particularly those, like Colon’s, that become problematic only after extended wear and tear.

“When I met Dan, I told him, ‘I’m scared. I’m not sure I want to find out what’s wrong.’ He said, ‘You’ve got to live so you can be there for your kids. Just stay for the testing and see how it goes.’”—Patient Jeanne Colon on Dr. Dan Halpern, Director of the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program

NYU Langone’s Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, one of the leading centers of its kind, serves patients with both previously and newly recognized cardiac defects. Besides providing state-of-the-art medical care, the program’s mission is to help patients cope with the stresses of a lifelong, and life-threatening, chronic illness. “It’s important to empower them,” says Dr. Halpern, who came to NYU Langone from Boston Children’s Hospital. “You have to give them the confidence to go out into the world.”

That approach enabled Dr. Halpern to connect with Colon as no other physician had. “When I met Dan, I told him, ‘I’m scared. I’m not sure I want to find out what’s wrong,’” she recalls. “He said, ‘You’ve got to live so you can be there for your kids. Just stay for the testing and see how it goes.’” His reassuring manner helped keep her from bolting again.

Dr. Halpern suspected that Colon’s constellation of symptoms resulted from a complication occasionally associated with untreated atrial septal defect: Eisenmenger’s syndrome. This circulatory disorder can arise from any heart defect involving a hole in the septum.

In a healthy heart, oxygen-rich blood courses from the lungs into the left atrium and downward into the left ventricle, from which it’s pumped with great force through the aorta and circulated throughout the body. Oxygen-depleted blood returns through the right atrium, flows into the right ventricle, and is pumped back to the lungs to be replenished. In a heart with a septal defect, blood typically leaks from the high-pressure left side into the lower-pressure right through the hole in the wall. This diversion, known as a left-to-right shunt, may send more blood to the lungs than they can easily handle. In Eisenmenger’s syndrome, the overburdened pulmonary capillaries form scar tissue, raising blood pressure in the lungs and forcing the heart to work harder to overcome it.

As the right side’s muscle tissue thickens, the pressure differential inside the heart is reversed, creating a right-to-left shunt. Now, oxygen-poor blood is pumped into the body, causing cyanosis and other serious problems.

Because the syndrome involves irreversible damage to the lungs, as well as structural changes in the heart, the only available options may sometimes be a heart–lung transplant or a lung transplant with heart surgery.

But Eisenmenger’s was far from the only possibility. “In this field, you sometimes come across a completely unexpected pathology,” Dr. Halpern says.

To unmask the culprit, NYU Langone’s congenital cardiac imaging team gave Colon the most detailed workup she’d ever had. “It’s not enough to just go in and take pictures,” observes Muhamed Saric, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and clinical director of noninvasive cardiology. “You have to have specialized knowledge so that you can interpret what you see.”

Dr. Halpern shepherded Colon through the process, offering emotional support as well as helpful explanations. First, Leon Axel, MD, PhD, professor of radiology, medicine, and neuroscience and physiology, conducted a cardiac MRI. Dr. Saric performed a transthoracic echocardiogram and a TEE, using a form of sedation for the latter that could be quickly reversed if Colon’s oxygen saturation became dangerously low. Finally, Michael Argilla, MD, clinical associate professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Catheterization Laboratory, inserted a catheter through Colon’s groin into the femoral vein. After measuring the direction and pressure of blood flow at key locations in her heart and lungs, he performed a “trial occlusion” of her septal defect, inflating a 3-centimeter balloon to block the shunt. The blood pressure in her right ventricle spiked, confirming that merely closing the hole would not solve her problems.

“My sons tell me, ‘You look better, Mom. You’re not sick all the time,’” Jeanne Colon reports, adding that she has grown close to Dr. Halpern, who continues to oversee her care. “I never trusted a doctor before, but Dan has been there for me every step of the way.”

When the results were in, the team members—including Puneet Bhatla, MD, associate professor of radiology and pediatrics, and director of pediatric and congenital cardiovascular imaging—agreed that Colon’s case was truly extraordinary. Her troubles stemmed not from Eisenmenger’s syndrome but from something far rarer—a pair of defects seldom found in tandem. In addition to a large atrial septal defect, she had a markedly undersized right ventricle, about half the normal dimensions. This raised the chamber’s internal pressure relative to the left side of the heart, creating an intermittent right-to-left shunt that mimicked Eisenmenger’s.

“I’ve seen something like this fewer than a dozen times in 20 years,” notes Ralph S. Mosca, MD, the Henry H. Arnhold Chair and Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery and chief of the Division of Pediatric and Adult Congenital Cardiac Surgery, who met with the group to map out a course of treatment.

The good news was that Colon’s lungs were undamaged, and her pulmonary pressure only slightly elevated.That allowed Dr. Mosca to suggest an approach that Eisenmenger’s would have ruled out: rerouting her faulty cardiovascular plumbing. The safest and most effective option, he explained, would be to combine a partial atrial septal defect closure with a technique known as a bidirectional Glenn procedure. Although this method is typically employed as part of a multistage repair process for babies born with a single ventricle, he had used it successfully on adults as well. Without such an intervention, the surgeon added, Colon’s health would likely continue to decline.

Colon consented to the plan, despite her fears. To maximize the chances of a positive outcome, she was sent home with oxygen canisters and medications aimed at lowering her pulmonary pressure. After three months, her readings were normal.

On a frigid morning in February 2016, Dr. Mosca and his team cut through Colon’s chest. After attaching her to a heart-lung bypass machine, they began the Glenn procedure, meticulously dividing the superior vena cava and sewing it onto the right pulmonary artery. Normally, the superior vena cava transports deoxygenated blood from the upper body to the right side of the heart. If the procedure worked as intended, it would divert one-third of that flow directly to the lungs, lessening the pressure that fueled Colon’s right-to-left shunt. One potential side effect, however, was that pressure could build up in the superior vena cava, causing swelling in Colon’s head. To prevent this, Dr. Mosca created a runoff channel using a nearby vein.

Next, he stopped Colon’s heart and opened up her right atrium. Using a small piece of pericardium, the membrane enclosing the heart, he made a patch to cover the septal defect, cutting a pinhole in the middle as an escape valve. Then, he restarted her heart, checked to make sure her blood was circulating properly, and stitched up her sternum with heavy wire. From start to finish, the operation took about four hours.

Colon’s recovery, like that of many patients who undergo open heart surgery, was slow and arduous. She spent a month in the hospital and was seen by visiting nurses for months after that.

Only recently has she gained enough stamina to begin cardiac rehab, doing supervised workouts at a gym three times a week. She still struggles with her weight (coached by NYU Langone nutrition consultants), with her medication regimen (assisted by patient-support workers), and with her longtime depression and anxiety (aided by a psychiatrist at NYU Langone).

But today, she can climb stairs and walk for blocks without tiring. Her chest pain and nausea are gone, and she can sleep without choking. She envisions returning to work in the near future.

“My sons tell me, ‘You look better, Mom. You’re not sick all the time,’” she reports, adding that she has grown close to Dr. Halpern, who continues to oversee her care. “I never trusted a doctor before, but Dan has been there for me every step of the way.”

Dr. Halpern, however, defers to his colleagues. “Adult congenital cardiology is an intensely collaborative field,” he says. “You’re often confronted with unique conditions that challenge your preconceptions. You need a team of specialists with the skills and experience to ask the right questions, and you can’t stop asking until you fully understand the answers.”