A Scientist Known for His Groundbreaking Research Turns Mentees Into Mentors

Graduate student Criseyda Martinez, Evgeny Nudler, PhD, the Julie Wilson Anderson Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and postdoctoral fellow Bibhusita Pani, PhD

Photo: Tony Luong

One scientist pursued a line of research that had previously stalled due to daunting challenges.

The other launched a spin-off project that headed in one direction before veering onto a tantalizing new trajectory. Through their perseverance and creative problem solving, two young researchers in the lab of Evgeny A. Nudler, PhD, the Julie Wilson Anderson Professor of Biochemistry at NYU Langone Health and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, have revealed promising new insights into how the human body responds to different forms of stress.

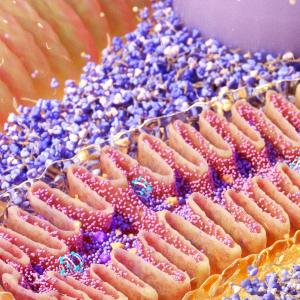

In humans and other animals, temperature changes are among the stressors that can activate what’s known as the heat-shock response. As part of this reaction, cells produce chaperone proteins that help other proteins fold. Researchers have linked the absence of these folding assistants and the ensuing clumps of misfolded proteins to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

“If you bring this chaperone activity back, most of these diseases can potentially be treated,” says Bibhusita Pani, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow and now research scientist in Dr. Nudler’s lab. “At the same time, other diseases like cancer are linked to too many of the chaperones.”

Understanding how chaperones are produced, then, could lead to therapies that ramp up their production to treat neurological disorders or decrease their output to treat cancers.

Dr. Nudler’s lab, known for its groundbreaking research on molecular mechanisms that control a variety of cellular functions, had implicated a specific RNA molecule in the heat-shock phenomenon. Dr. Pani joined the lab in 2011 after receiving her doctoral degree at the Center for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics in India and conducting postdoctoral research on RNA splicing at Rockefeller University. At NYU Langone, says Dr. Nudler, she was eager to take on his lab’s hardest project: figuring out exactly how the heat-shock-linked RNA works.

“The more difficult something is, the more she wants to work on it and overcome the challenge,” he says. “That’s what drives her. I really cherish this aspect of her work. It’s a rare combination of very high technical skills and high creativity but also boldness.”

Dr. Pani has discovered that the RNA molecule works like a thermometer: Once a certain temperature is reached, the molecule turns on chaperone production.

Understanding this mechanism allowed her to reengineer the RNA in human cells so that it activates at 37 degrees Celsius—normal body temperature—and can be introduced into brain cells to prevent protein misfolding. That success has led to the testing of several drug candidates for neurodegenerative disorders.

Like Dr. Pani, graduate student Criseyda Martinez chose the Nudler lab because it gave her the freedom to explore new ideas and the opportunity to work on challenging, high-impact research.

Martinez received her master’s degree in parasitology from San Francisco State University before enrolling in NYU Langone’s Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences in 2011. She liked the way Dr. Nudler explained his research projects and goals, and she found Dr. Pani’s enthusiasm infectious. “She was so excited about her research—that really drew me to the lab,” Martinez recalls.

Martinez soon found herself working closely with Dr. Pani on a project that branched off from her heat-shock studies.

Dr. Pani advised her in writing grants, planning experiments, and honing other skills that have furthered her own goal of an academic career. Martinez also took courses in science writing, project management, and entrepreneurship.

The mentoring, constructive criticism, and encouragement have been invaluable in increasing her skills, confidence, and independence, she says.

With Dr. Pani’s help, Martinez discovered that a protein initially thought to play a role in the heat-shock response instead binds to certain RNA molecules in ways that repress the body’s immune response to stress. “That was a very unexpected turn,” Dr. Nudler says. With sophisticated tools, Martinez found that removing this protein from cells dramatically increased their production of an infection-fighting molecule called interferon and turned on a pathway that caused stressed cells to self-destruct. “If we can target this protein to inhibit it, we can initiate responses that are important for combating bacterial and viral infections,” she says. Other research has linked the same protein to cancer development.

“If we can suppress this protein, we can target cancer as well,” she says.

For someone who loves thinking and solving puzzles, Martinez says putting the pieces together to reveal the protein’s previously unknown function has been deeply rewarding. “It’s the satisfaction of knowing I accomplished something,” she says. Dr. Nudler attributes her success to her thoroughness, intelligence, and resilience. When Martinez’ research didn’t go the way she expected, he says, her willingness to try a different tack took the lab’s research in an entirely new direction that may eventually blossom into an even bigger reward: a new way to design a range of badly needed clinical therapies.

The Meaning of Mentorship

Mentorship can be just as much about helping yourself as helping others. For this reason, among others, Dr. Nudler encourages all of his postdoctoral fellows to spend time guiding and advising graduate students. “It’s very important for their development as future supervisors,” Dr. Nudler says. Postdoctoral fellow Dr. Pani, who has mentored graduate student Criseyda Martinez for the past six years, says the experience has made her a better communicator. “One thing that really improves with being a mentor is your ability to explain what you’re thinking,” she says. Clear and concise explanations, she adds, have been especially helpful for writing grants and journal articles.