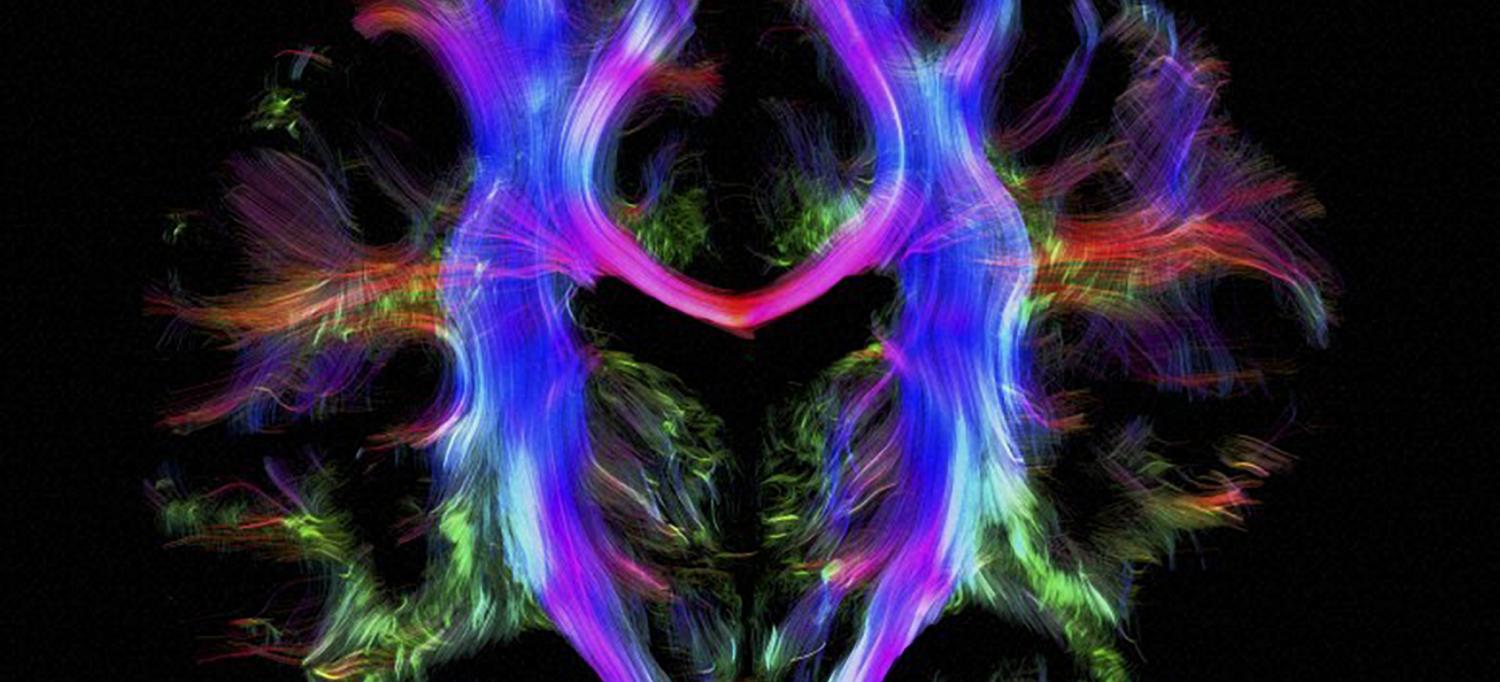

Nerve fibers in the brain of a young healthy adult.

Photo: Alfred Anwander, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Wellcome Images; http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In multiple sclerosis, the malfunctioning immune system targets an insulation-like cover called myelin that protects nerve fibers within the brain and spinal cord. Progressive loss of myelin leaves these fibers and the neurons that form them vulnerable to damage and destruction, eroding the brain’s ability to communicate with the body.

Based on experiments with mice afflicted by a similar condition, NYU Langone researchers have discovered a new way to potentially fix some of the damage and reverse the symptoms of multiple sclerosis. “There are stem cells within the brain that can contribute modestly to repairing lesions, in particular ones that involve myelin loss,” says study coauthor James Salzer, MD, PhD, professor of cell biology, neurology, and neuroscience. “But we found a way to coax them and make them much better at it.”

The finding centers on sonic hedgehog, a well-studied gene whose encoded protein directs early brain development by sending signals that turn on other genes. Some scientists had suggested that boosting this protein’s signaling activity might aid myelin repair.

Instead, Dr. Salzer and colleagues have found just the opposite. “The big surprise from our study was that one of key endpoints in the hedgehog pathway actually turns out to be a brake on myelin repair,” says Dr. Salzer, whose team recently published its findings in the journal Nature.

In one set of experiments, the researchers effectively released that brake by genetically depleting the brain’s stem cells of GLI1, one of the genes normally turned on by sonic hedgehog. This disruption in hedgehog-directed signaling, they found, allowed the stem cells to be converted into a bigger crew of myelin-manufacturing specialists.

A second set of experiments yielded similar results. The scientists first inoculated mice with a protein that provoked the immune system to attack the neurons’ myelin covering, and then treated half of the afflicted animals with an experimental drug called GANT61, which has been previously shown to target GLI1. After a month on the drug, previously paralyzed mice regained most of their mobility, while their untreated counterparts remained severely disabled. At the cellular level, the treated mice retained 50 percent more myelin, on average, and lost far fewer of the motor neurons that control movement in the lower extremities. By inhibiting the GLI1 protein, the GANT61 drug may free up the brain’s stem cells to orchestrate the necessary myelin repairs.

Translating these findings into an effective therapy will require a better understanding of how GLI1 proteins behave in humans, and Dr. Salzer believes a more potent drug will be needed. Even so, he says, the discovery of an “exciting target that hadn’t been explored” and his experimental results have earned his group a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and provided new momentum toward a badly needed clinical intervention.