NYU Langone researchers aim to understand chronic dysphagia and dysphonia that may follow anterior cervical discectomy and fusion spine surgery.

Photo: Jose Luis Pelaez Inc

A new, multidisciplinary study led by speech–language pathologists and physicians in the Department of Communicative Sciences and Disorders at NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Neurosurgery, and Rusk Rehabilitation at NYU Langone Health is aimed at elucidating the causes and mechanisms behind long-term dysphagia and dysphonia in patients who have anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) spine surgery.

Little is known today as to why some ACDF patients experience ongoing swallowing issues for months following surgery, while others’ problems are limited to temporary disruption associated with postsurgical edema. Generally, problems related to postsurgical edema alone are expected to resolve in the first few months after surgery; patients who are still experiencing dysphagia after that timeframe are referred to speech–language pathology for a swallow evaluation. Since dysphagia can lead to aspiration, causing complications such as pneumonia and hospitalization, the condition presents more than inconvenience to affected patients.

Distinguishing Expected Swelling from Atypical Swallowing

“ACDF patients almost universally experience some disruption to their swallowing, since they’ve had their neck opened and an invasive procedure in that space,” explains Sonja Molfenter, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Communicative Sciences and Disorders at NYU Steinhardt. “What’s less understood is how to identify which patients experience changes to the neurovascular structures involved in swallowing, or why and how a subset of these patients go from being disrupted during postsurgical recovery to longstanding dysphagia.”

In collaboration with Stamatela Matina Balou, PhD, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Dr. Molfenter is investigating whether it is possible to predict which patients might fall into the smaller subset with long-standing, debilitating disruption in swallowing. Their research began with a systematic literature review of 2,000 articles to determine the prevalence of prior studies investigating the problem. They found an under-examination of the issue, with the few identified studies limited to retrospective or underpowered designs. Nearly half of studies that described the problem of dysphagia after ACDF utilized the Bazaz scale, a simple, two-question, patient-reported measure.

“This is a multifactorial problem that demands more than a yes/no analysis.”—Matina Balou, PhD

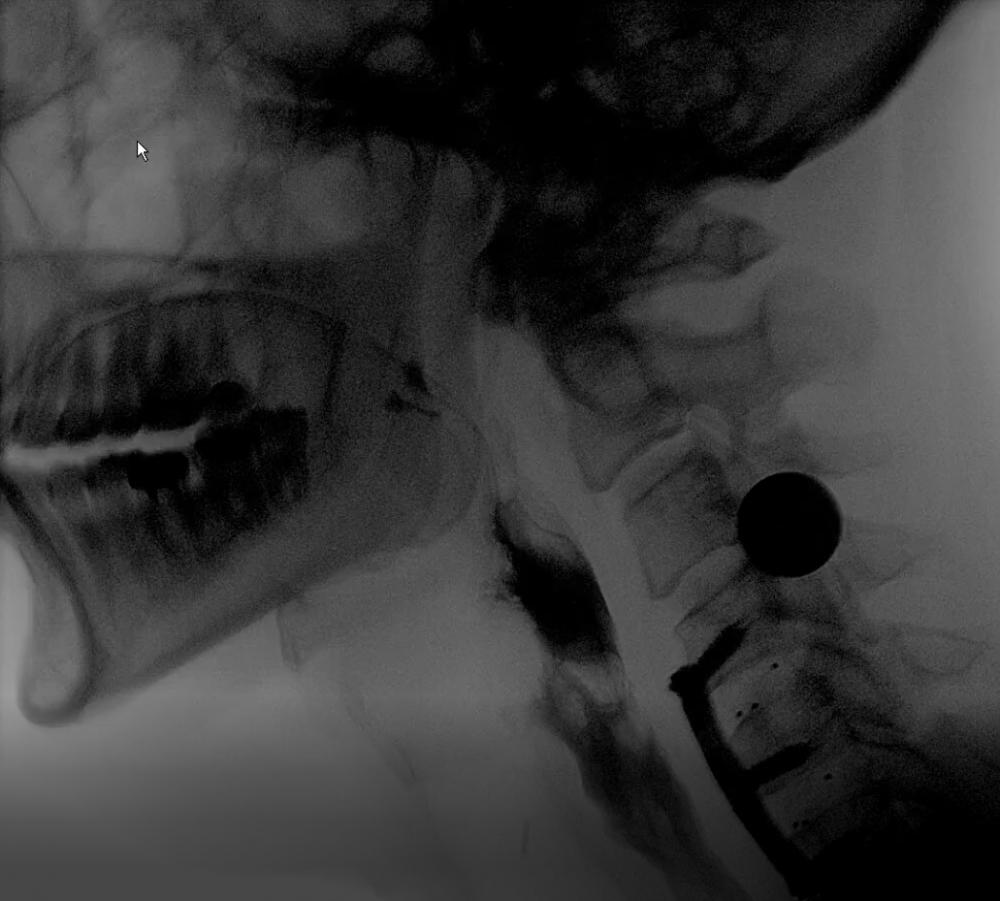

“This is a multifactorial problem that demands more than a yes/no analysis,” says Dr. Balou. “When we follow these patients at our center, we typically perform a much more in-depth radiographic assessment, with a barium swallow, to determine the extent of structural involvement in the patient’s symptoms.”

Identifying Predictive Measures for Earlier Intervention

Working with neurosurgeon Anthony K. Frempong-Boadu, MD, co-director of NYU Langone’s Spine Center, the team is now engaged in a one-year pilot study that will follow 20 patients through their ACDF surgery and recovery. Patients will be examined through two visits at NYU Langone’s Voice Center—both pre-ACDF and six weeks post-ACDF—with the research team conducting three primary evaluations: a swallowing study, measures of pharyngeal edema using an acoustic pharyngometer, and an acoustic voice sample. The team hopes to determine whether the latter two approaches can be validated as accurate noninvasive measures of edema, pilot data they hope will pave the way toward a future National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded, multicenter research study. An additional goal is to describe the physiology of swallowing post-ACDF, in hopes of uncovering data to predict which patients might experience long-term impairment.

“Currently, by the time patients come to us with symptoms, they have already suffered for several months,” notes Dr. Balou. “If we can identify an algorithm that would let surgeons know a patient is high-risk for long-term problems, we could recognize what’s happening and intervene at patients’ first complaint—potentially restoring their quality of life sooner.”