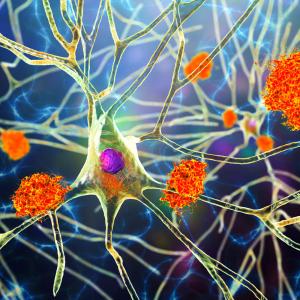

Photo: JUAN GAERTNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Despite the 25-year focus on the buildup in brain tissues of one protein, amyloid beta, as the purported origin of Alzheimer’s disease, a new study argues that it is likely triggered instead by the failure of a system that clears wastes from the brain—and actually begins decades before memories fade.

Based on findings published online February 7 in the journal PLOS ONE, researchers from NYU School of Medicine demonstrate that the current biological understanding of Alzheimer’s disease is incomplete. The new evidence suggests that standard diagnostic tools fail to catch future risk for the disease in many patients younger than age 70, say the study authors.

In the commonly held definition of Alzheimer’s disease, one type of amyloid-beta (Aβ42) starts to form clumps between nerve cells, injuring them. Worsening injury is then marked by the release and toxic buildup of a second protein called tau. Together, changes in Aβ42 and tau levels represent the standard international measure of a person’s risk for future cognitive decline.

The new study found that the buildup in the brain of amyloid beta cannot be the sole trigger of subsequent nerve damage because many relatively younger people who develop disease later do not show signs of the buildup.

“Once you stop assuming that the starting point of Alzheimer disease is marked by the buildup of Aβ42 in brain cells, a different picture emerges,” says lead study author Mony J. de Leon, EdD, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and director of the Center for Brain Health, at NYU Langone Heath. “By recognizing an earlier disease phase, we may be able to start treating earlier and in tailored ways based on a better understanding of disease biology.”

For many years, neuroscientists have sought to predict Alzheimer’s disease risk by tracking protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that fills the spaces around brain tissue, and which can be sampled by lumbar puncture as part of a spinal tap. In 1999, Dr. de Leon and colleagues started collecting clinical and CSF protein level data from healthy normal subjects every two years. Combining this NYU Langone database with two others, the current study is the largest of its kind to date, including roughly 700 patients.

Specifically, the study found that the best predictor of future Alzheimer’s disease risk was not, as currently thought, decreased CSF Aβ42 levels with elevated tau. Elevated CSF Aβ42 levels were also found to confer future risk.

By including in risk prediction models patients with either rising or falling CSF Aβ42, along with steadily rising tau, the team increased the accuracy of future risk prediction by nearly 20 percent over current models, which only consider falling levels. The improved accuracy was even more pronounced in those aged younger than 70 years, Dr. de Leon says. In mathematical terms, the relationship between Aβ42 and tau is best described by a quadratic equation rather than the current linear one, which attempts to make a curve “fit” onto a straight line.

The results add to the evidence that an increase in CSF tau over a lifetime may be the more relevant, early feature of Alzheimer’s disease than a drop in CSF Aβ42, taken as evidence of a buildup in brain cells, researchers say.

While the actual mechanism behind Alzheimer’s disease and the trajectory of Aβ42 and tau levels remains obscure, say the authors, the results provide evidence in support of the “clearance theory.” It holds that the pumping of the heart, along with constriction of blood vessels, pushes cerebrospinal fluid through the spaces between brain cells, clearing potentially toxic proteins into the bloodstream. Mid-life cardiovascular changes that bring on heart failure and hypertension may lessen the CSF flow needed to clear tau, and perhaps disease-causing proteins yet to be identified.

Aside from Aβ42, which is readily deposited into the brain, the team found that CSF levels of two other common forms of amyloid beta that are less able to build up, Aβ38 and Aβ40, increase in proportion to rising tau throughout the normal older adult lifespan, even after CSF Aβ42 starts to decrease. This is further evidence of a decline in clearance with age, researchers say.

“Future CSF studies need to follow normal subjects, starting at age 40, for decades to get an unbiased look at the trajectory of CSF proteins and the likelihood of developing cognitive impairment decades later,” says Dr. de Leon.

Along with Dr. de Leon, study authors from NYU School of Medicine included co-first author Elizabeth Pirraglia, Ricardo Osorio, Lidia Glodzik, Silvia Fossati, Eugene Laska, Carole Siegel, Tracy Butler, and Yi Li in the Department of Psychiatry’s Center for Brain Health; and Henry Rusinek in the Department of Radiology. Some authors were also faculty in the Department of Population Health and at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research.

Study authors also included Les Saint-Louis of Lennox Hill Radiology in New York; Hee Jin Kim of the Department of Neurology at Hanyang University in Seoul, Korea; Juan Fortea of Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain; and Kaj Blennow and Henrik Zetterberg of Sahlgrenska University Hospital at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. The study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants P30 AG019610, P30 AG013846, P50 AG008702, P50 AG025688, P50 AG047266, P30 AG010133, P50 AG005146, P50 AG005134, P50 AG016574, P50 AG005138, P30 AG008051, P30 AG013854, P30 AG008017, P30, AG010161, P50 AG047366, P30 AG010129, P50 AG016573, P50 AG016570, P50 AG005131, P50 AG023501, P30 AG035982, P30 AG028383, P30 AG010124, P50 AG005133, P50 AG005142, P30 AG012300, P50 AG005136, P50 AG033514, P50 AG005681, and P50 AG047270.

Media Inquiries

Greg Williams

Phone: 212-404-3500

gregory.williams@nyumc.org