Using a nuanced and multistep surgical approach, laryngologist Dr. Milan R. Amin treats a patient’s severe esophageal stricture, a side effect of her cancer treatment.

Photo: NYU Langone Staff

When a 71-year-old female patient presented with hypopharyngeal strictures and complete esophageal stenosis following chemoradiation therapy for thyroid cancer, experts at NYU Langone’s Voice Center developed a multistep surgical treatment plan that resolved the patient’s troublesome symptoms and restored her swallowing function.

Aggressive Cancer Therapy a Success, with Side Effects

Diagnosed with anaplastic thyroid cancer—an aggressive cancer with a low survival rate—the patient previously had an aggressive surgical thyroidectomy and lymph node dissection with subsequent postoperative chemoradiation, leaving her cancer-free. However, the success of the treatment was marred by untenable side effects—over the following year, she developed progressive dysphagia. Ultimately, she was unable to eat or swallow without aspirating.

“The esophagus is well within the radiation field when you’re treating the thyroid, so as you target cancer’s rapidly dividing cells, you also reach the mucosa of the esophagus,” explains Milan R. Amin, MD, professor in the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery and director of the Voice Center. “Over time, that raw wound contracts and forms a scar—which becomes a stricture.”

At the time the patient was referred to Dr. Amin, her quality of life was seriously impeded by a complete esophageal stricture, which was confirmed by an X-ray. Her inability to swallow necessitated a gastric feeding tube and caused her to continually bring up saliva tinged with yellow mucus. Though surgical intervention was needed, the typical dilation method to relieve such strictures would carry too much risk in this case.

“We see strictures frequently from radiation to the head and neck, but they’re typically just narrowed, so you can simply go in and dilate them,” Dr. Amin notes. “In the case of this severe stricture, you risk dilating inappropriately, causing a tear and exacerbating the issue.”

Dual Approach to a Safe Dilation

The patient’s surgical plan required a more complex approach, establishing a tract and then dilating the stricture with a combined retrograde and anterograde procedure. To safely dilate in the correct location and minimize the risk of tears, the approach—known as a rendezvous procedure—endoscopically identifies the stricture from above and the esophagus from below. The procedure typically requires several surgeries to gradually create an opening.

“If you overstretch, you create a tear, so you’re not getting to the full caliber of where the esophagus needs to be in one surgery,” Dr. Amin says. “And because of the radiation, as the tissue heals, it wants to contract back—so with these patients we talk about taking three steps forward, two steps back.”

Although safer than an open approach, the nuanced rendezvous approach is not without risks, including tears and mediastinal infection in the delicate post-radiation tissues. “It takes a significant level of expertise to manipulate both scopes simultaneously; most otolaryngologists have never placed a scope in retrograde from the stomach up to the esophagus,” notes Dr. Amin, who has performed several of those procedures in patients with significant strictures.

Series of Surgeries Reduces the Stricture

With the multistep surgical plan created, the first surgery began with a rigid approach to the esophageal inlet, while a flexible esophagoscope was placed through the patient’s gastrostomy site after the tube was removed.

“We typically get an esophagram to try and identify how thick the narrowing is, but since barium cannot pass through the stricture in these cases, we discover how long the stenosis is at the time of surgery,” Dr. Amin says.

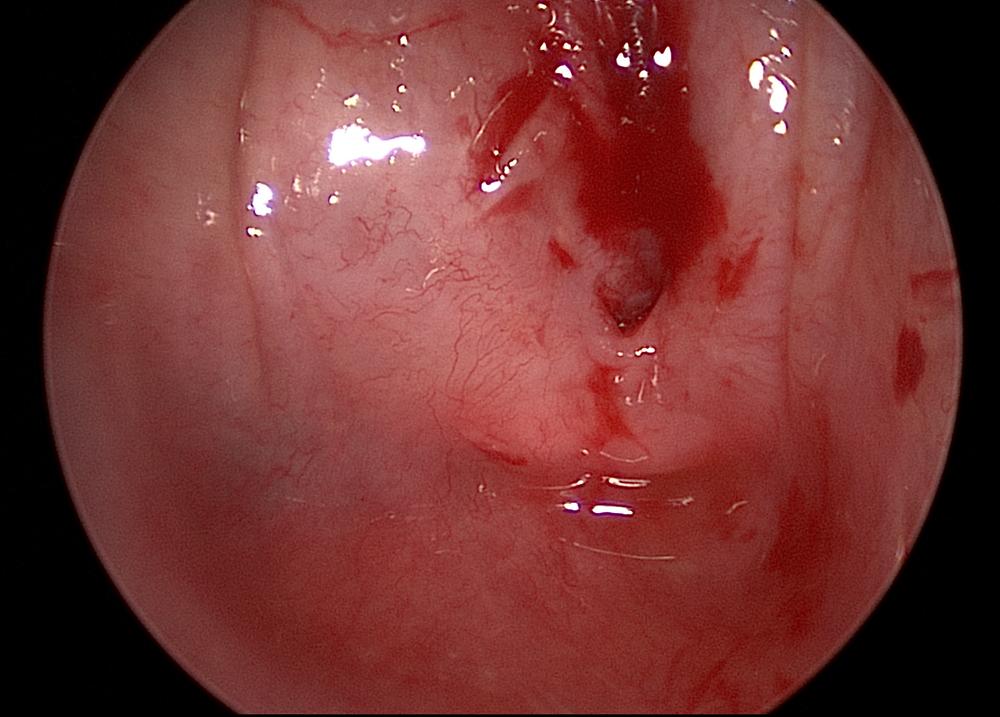

With the endoscope directed up to the proximal esophagus, the team visualized a complete stricture. A small, partial tract was noted and cannulated with a suction catheter, which could be seen through the retrograde view.

With an initial path created, the catheter was passed into the distal esophagus, and a balloon dilator widened the esophagus. Aided by direct visualization from above and below, doctors passed a nasogastric tube through the opening and into the esophagus and then the stomach, and sutured it to the nasal cavity.

“The body naturally wants to re-create the stricture, so we use the nasogastric tube as a stent for the first few procedures until we are confident the opening won’t reclose,” Dr. Amin notes.

An identical approach was used across 4 repeat balloon dilations over 12 months to achieve a gradual, near-complete opening of the stricture.

A Return to Food

Eight months after surgery, this patient’s life-altering symptoms have subsided significantly, with swallowing and eating functions restored to near-normal levels. A recent esophagram shows a slight recurrence of stricture, which the patient has elected to fine-tune with a final surgery. Additionally, she is now two years post-cancer treatment and continues to have a favorable prognosis.

Dr. Amin and his team are applying for funding to support investigations into chemoradiation’s impact on surrounding tissues of the head and neck, with the ultimate goal to enhance prevention and treatment methods, and maintain patients’ quality of life during and following treatment.

“For this patient, our surgical approach completely restored functions whose absence created a fairly miserable existence,” Dr. Amin says. “She was carrying around tissues, constantly spitting because she couldn’t swallow, and unable to have meals with her family. Now she can enjoy life, and eating, once again.”