Neil D. Theise, MD, Found that the Interstitium, Long Thought to be Mere Connective Tissue, Serves a Unique & Critical Function

Pathologist Neil D. Theise, MD

Photo: Sasha Nialla

In March, when Neil D. Theise, MD, published a study in Scientific Reports promoting an unsung network of fluid-filled compartments beneath the skin—known collectively as the interstitium—as a full-fledged human organ, he knew he was onto something big. He just didn’t know how big. The report was greeted by 2,400 news articles, nearly 3.8 billion online views, and no small bit of controversy, as scientists continue to debate the implications of his discovery. For his part, Dr. Theise, professor of pathology, is more interested in uncovering the intricacies and implications of what would, if accepted by scientific consensus, be the human body’s 80th organ.

There’s debate over whether the interstitium, long thought to be mere connective tissue, qualifies as an organ. What’s your take?

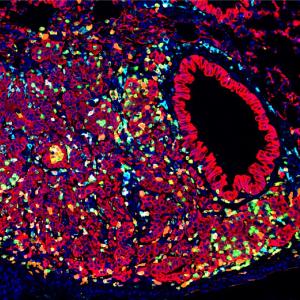

There’s no governing body that says, “Yes, this meets the definition of an organ.” It’s how the collective community treats it over time. But to me there’s no doubt it’s an organ. The interstitium is large and present in many places: beneath the skin, in the lining of all the visceral organs, in the fascia between all muscles, and in the connective tissue around every artery and vein. Wherever you examine it, the structure is unitary and unique, which is one qualification for being an organ.

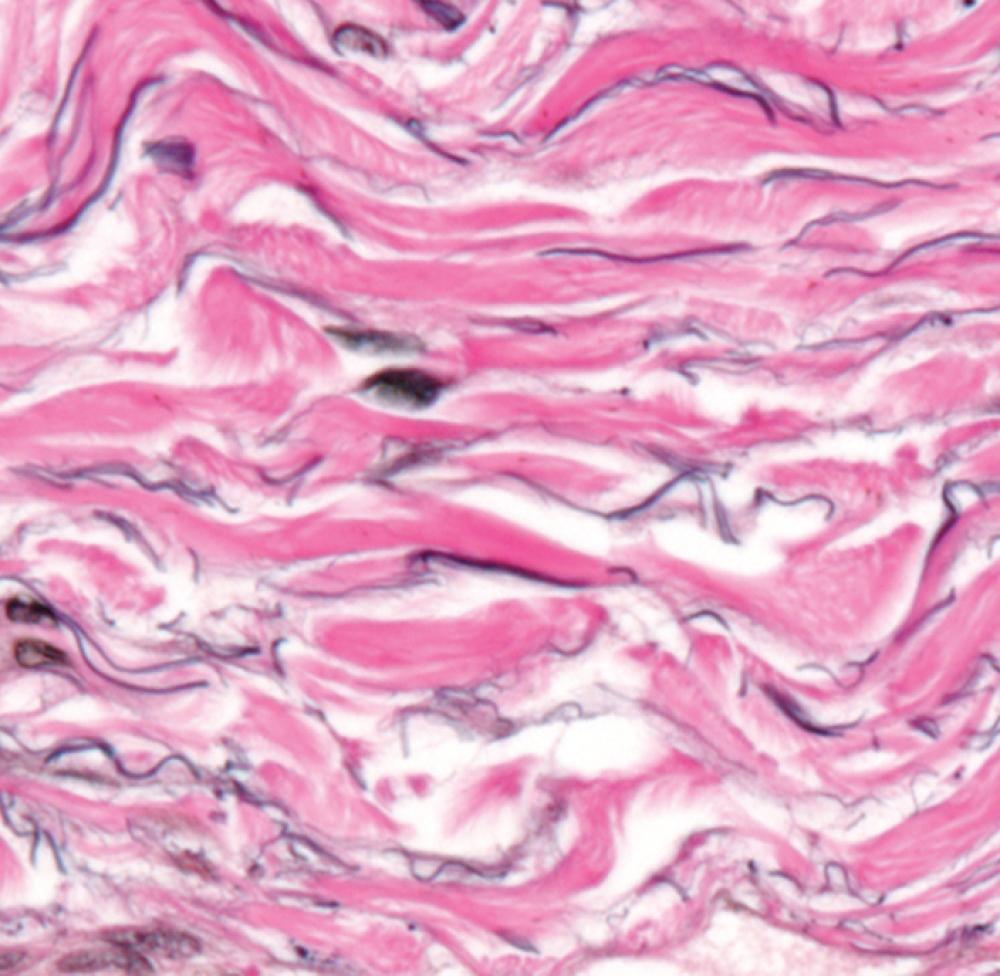

Another qualification is that it serves a unique and critical function. We strongly believe it has a shock-absorber effect that protects tissue from the constant movement of organs, like peristalsis in the digestive tract. No one seems to have questioned why this dense connective tissue around the body doesn’t wear down and tear over time. But that’s because it’s not stiff—it’s fluid-filled space that’s compressible.

What has surprised you most about the scientific community’s response?

I knew there would be pushback and criticism because that comes with anything that changes paradigms. We’re an interdisciplinary research team, so far including endoscopists, a hepatologist who is also a cell and molecular biologist, and a pathologist. We came in from left field, and naturally those who are in the fascia world or the interstitial world say, “Who are you to say we missed all of this stuff?” I would have the same resistance if someone from neuropathology made a liver discovery that upended my assumptions.

Despite the study’s significance, scientific publishers weren’t breaking down your lab door to publish it, were they?

We sent it to all the top biomedical journals. None of them even reviewed it because they didn’t think it would be of interest to their audience. Well, it turns out they were wrong. Every time we got a rejection letter, I thought, “We’re onto something so big they can’t see it.”

How have you handled the massive response?

The media explosion kept me very busy. I experienced four days of fame, and now it’s over—and that’s a relief. The more important thing is that we suddenly have these relationships with physicians and scientists around the world who are picking up on this new understanding of the interstitium and running with it. We have to adjust to the idea that we’re not going to be able to do all the work on this project, and pretty soon we won’t even be able to keep up. The baby is up and walking.

Could the interstitium lead to new categories of disease diagnosis?

Absolutely. Patients have been emailing me saying, “I have a very rare, unclassifiable disease, and I think what is diseased is what you’ve discovered.” The condition that’s popped up the most is fibromyalgia. Scientists can’t even agree on whether it’s a single physiological disease. Maybe the reason why fibromyalgia has been opaque is because we haven’t recognized the compartment of the body that’s affected.

If this organ is present in every tissue and other organ the way the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems are, then we have an incomplete understanding of the entire body. This is basic anatomy, basic physiology. I don’t think there’s anything that doesn’t get changed by this.

You made this finding with technology that allows you to observe living cells instead of studying dead cells fixed on a slide. Does this approach have broader implications for other parts of the body?

Everything we know about the body is a reflection of the methods we use to examine it. I had been looking at the interstitium for 30 years and never really noticed it before. The history of microanatomy is that first we simply looked through a microscope without any special preparation techniques. Then, we learned to fix tissues in formaldehyde and to stain them to highlight molecules or structures. Now, we’re viewing living tissue at the microscopic level, which has enabled us to stumble onto this.

Scientists tend to look at certain aspects of the human body as being inert. But the body is an ecosystem, not a machine. Nothing is without a biological purpose, and you can’t change one piece without everything else changing. It’s all interwoven.