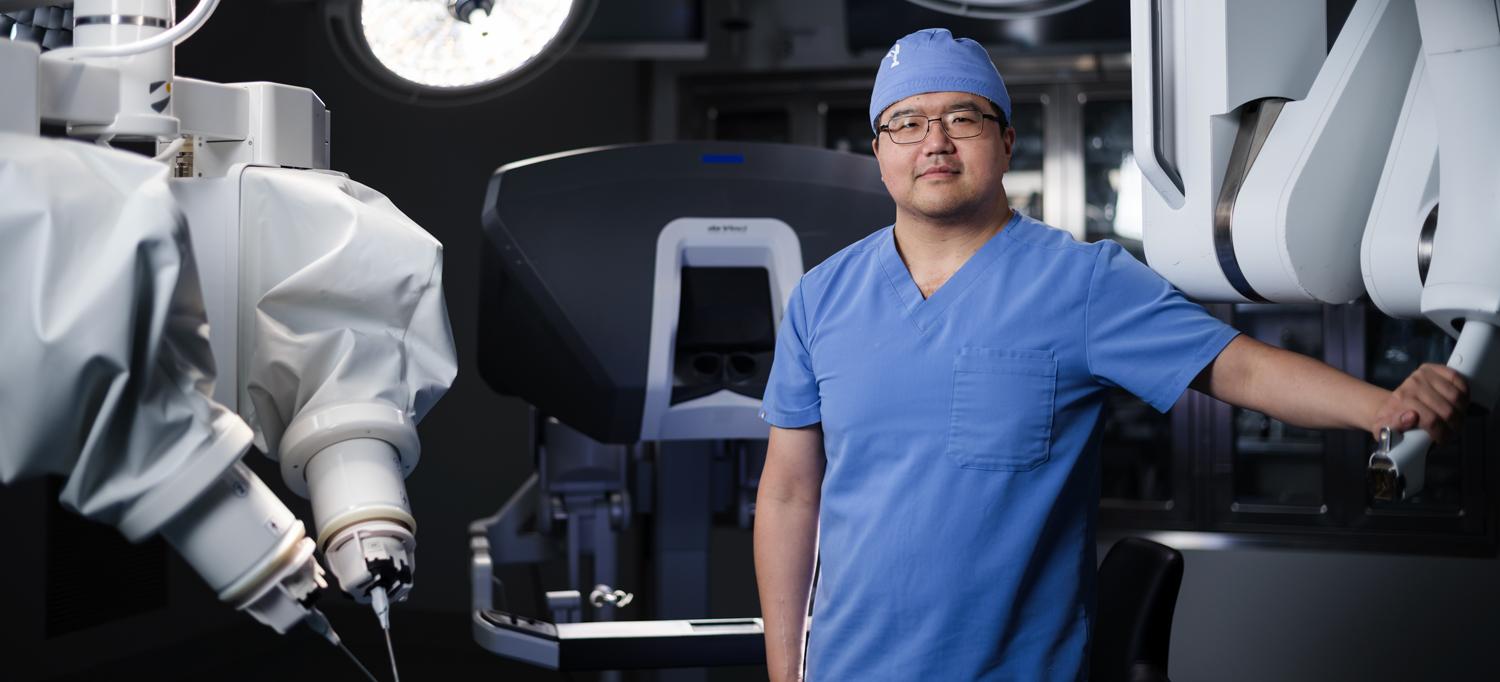

Confronted with a challenging case, NYU Langone’s kidney transplant surgeons turned to Dr. Lee Zhao, a urologist and reconstructive surgeon who has pioneered other robot-assisted surgical techniques.

Credit: Karsten Moran

By early 2024, Elliot Vargas was long overdue for some good news. The 49-year-old ambulette driver from Brooklyn had been battling diabetes for three decades, and for more than two years had endured dialysis to manage end-stage kidney disease induced by the condition. Vargas’s unrelenting treatment regimen—three days per week, up to five hours each time—put an end to the vacations he and his wife, Natalie Vazquez, 42, often enjoyed in Florida and the Caribbean. When his mother, Elfega, died in 2023, he had no choice but to miss her burial in Puebla, Mexico.

A kidney transplant might restore Vargas’s quality of life, but before qualifying, he had to undergo several rounds of tests. “With Natalie’s support, he never lost hope,” says Nicole M. Ali, MD, medical director of NYU Langone Health’s Kidney Transplant Program. “The caregiver plays a vital role because the long, complex transplant journey can take a tremendous mental toll on the patient, just as dialysis takes a physical toll.”

The support that Vazquez, a manager in the mental health field, provided turned out to be even greater than Vargas could have imagined. She pledged to donate one of her kidneys to her husband, and genetic testing determined that she was a strong match. Vazquez’s two kidneys, though, were not equal; her left kidney provided greater function than her right one. Typically, a living donor’s left kidney is extracted because its renal vein is longer than the right kidney’s, making it easier to connect the blood vessels to the recipient’s iliac artery and vein. A kidney removal, or nephrectomy, is more technically demanding on the right side due to the shorter renal vein and the kidney’s proximity to the liver, a large organ, and the vena cava, the large vessel that returns blood to the heart. But if Vazquez’s left kidney were removed, she would be at greater risk for kidney problems in the future. “It’s important to make sure kidney donation is as safe as possible for the donor,” notes Dr. Ali, “and at the same time have an organ that can be transplanted successfully. If one kidney is smaller than the other, it’s better to leave the donor with the larger, more robust kidney.”

The team at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute determined that Vazquez’s right kidney would provide sufficient function for her husband without compromising her long-term health. To perform the complex operation, they turned to urologist and reconstructive surgeon Lee Zhao, MD. “We knew Dr. Zhao had a lot of experience removing cancerous kidneys,” says Dr. Ali, “but removing a kidney that needs to be transplanted requires a different technique, preserving blood vessels, leaving as much length as possible for the transplant surgeon, and handling the organ very gently.”

Jonathan C. Berger, MD, surgical director of the Kidney Transplant Program, and the transplant team discussed the case with Dr. Zhao. “I looked at the images,” recalls Dr. Zhao, “and I said, ‘Yes, I think I can do it.’”

Dr. Zhao’s confidence stemmed from two sources. As a member of NYU Grossman School of Medicine’s Department of Urology, which is No. 2 nationwide in U.S. News & World Report’s Best Hospitals rankings, he had previously pioneered surgical techniques to resolve complex urological problems. Moreover, he had a peerless partner in the operating room: the da Vinci single-port robotic surgical system. NYU Langone was the second institution in the world to acquire the technology back in 2018. “Over the years, we’ve gradually improved our technique for safely removing a kidney through a single incision,” notes Dr. Zhao.

Traditionally, right kidneys have been extracted using a minimally invasive approach, with several incisions and the insertion of a thin tube with a camera, called a laparoscope, through the peritoneal cavity that surrounds the intestine. But this approach risks an injury to the bowel. The retroperitoneal procedure devised by Dr. Zhao creates a small workspace behind the abdominal cavity, avoiding the peritoneal cavity entirely. Dr. Zhao makes a single 2.5-inch-long incision—wide enough to insert robotic surgical instruments and a camera that affords a 360º view—in the donor’s right flank. “This new technique gives us better access to the renal artery and vein and a direct view of these vessels,” Dr. Zhao explains. After dissecting and freeing the kidney, a process that takes about two hours, he removes the organ through the same incision.

On May 20, 2024, Dr. Zhao used the novel approach to extract Vazquez’s right kidney. Bruce E. Gelb, MD, then transplanted the organ into her husband. Both surgeries were performed at the same time in adjacent operating rooms. On the day before Vargas’s final dialysis treatment, Vazquez was preparing goodie bags for Vargas’s dialysis nurses when she realized that her husband would no longer need to return to the clinic for treatment. “Tears of joy ran down my face,” she recalls. Vazquez went home the next morning, less than 24 hours after surgery, and made a speedy recovery. Vargas spent two weeks recovering in Kimmel Pavilion and was able to resume his job and normal activities within three months. His renal function is now considered excellent, and he is back to traveling. In fact, one of the first trips he made postsurgery was visiting his mother’s grave.

NYU Langone is the only health system in New York City that performs single-port, robot-assisted, retroperitoneal, right-sided donor nephrectomies, often with same-day discharge. In April 2025, Dr. Zhao described the landmark case at the American Urological Association annual meeting. “The early results have been excellent,” he told colleagues. “We believe this technique is both feasible and reproducible.” To date, Dr. Zhao has successfully performed the procedure using the single-port technique—assisted by Dr. Gelb and his colleague Jeffrey Stern, MD—on 10 kidney donors, all of whom made rapid recoveries. Transplant surgeons Dr. Gelb and Dr. Stern have increasingly been using the da Vinci robot for left-sided kidney donations as well.

Dr. Zhao’s breakthrough may prove transformative. More than 90,000 people in the United States are on the wait list for a kidney, but less than one-third can expect to receive a transplant. In 2024, living donors made 6,418 kidney transplants possible; only 16 percent of transplanted kidneys are extracted from a donor’s right side because of the technical difficulty of right-side donor nephrectomy and transplantation. Once more surgeons master this robotic procedure, the benefits of a faster, easier, and less painful recovery are likely to encourage more people to become kidney donors. “The ability to perform a nephrectomy on either side of the body without compromising outcomes could greatly expand the pool of living donors by including those who would have otherwise been deemed ineligible,” notes Dr. Zhao.