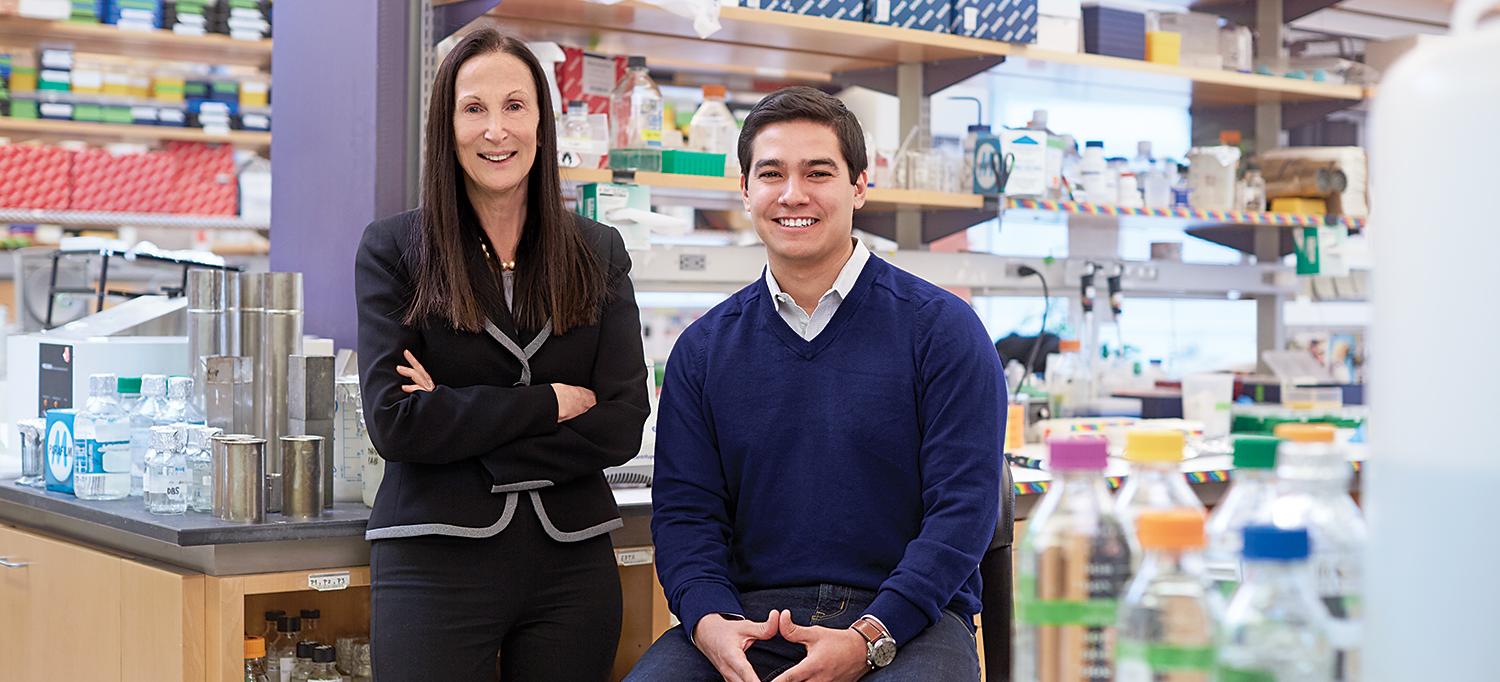

When a Newly Minted PhD Sought to Parlay His Research Into an Entrepreneurial Venture, He Found a Supportive Partner in His Mentor

Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, professor in the departments of Medicine and Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, senior vice president and vice dean for science, and chief scientific officer, and postdoctoral fellow Craig Ramirez, PhD

Photo: Jonathan Kozowyk

Craig Ramirez, PhD, is a self-described “puzzle person” who loves the challenge of solving a difficult problem. “To me, that’s essentially what research is,” he says. “If you take your mind off everything else, it’s a puzzle, and you’re trying to piece it together.”

Few problems are more perplexing—and more important to solve—than a cancerous tumor, with its swirling universe of heterogeneous cells, mutated genes, and environmental triggers. “It’s a pretty intense puzzle,” he says.

After graduating from Pomona College in Claremont, California, in 2011, Dr. Ramirez was attracted to NYU Langone Health by its high-quality research, strong federal funding, and the flexibility of its Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, which allowed him to explore multiple research interests. Ultimately, though, he was drawn to the lab of Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, senior vice president and vice dean for science, and chief scientific officer, by the opportunity to help solve a longstanding enigma in cancer biology that might reveal how to exploit weakness in a growing tumor.

Dr. Ramirez earned a PhD in 2017 through his doctoral research on macropinocytosis, a cellular process that Dr. Bar-Sagi, professor of medicine and biochemistry and molecular pharmacology, first described in the 1980s. “Macropinocytosis is a way that cancer cells drink and obtain nutrients from the tumor microenvironment,” Dr. Ramirez explains. The process is controlled by a protein called Ras, which drives one-third of all cancers.

“Because this is a way that cancers are able to support their metabolism, it could potentially be a good therapeutic target,” he says. “Unfortunately, there’s not much known about how this process is regulated, so the overarching theme of my research is to better understand the molecular regulators behind it.”

To identify the molecules that allow these cancer cells to access the nutrients in nutrient-scarce environments, Dr. Ramirez and colleagues in the Bar-Sagi Lab used a small piece of interfering RNA to sequentially knock out the activity of the roughly 18,000 genes spanning the human genome. For each gene they inhibited, the researchers tested whether the cancerous cells’ macropinocytosis process had been disrupted. Based on the effects Dr. Ramirez saw after blocking specific genes, descriptions that he read in the scientific literature, and follow-up experiments, he was able to piece together a pathway driving macropinocytosis. “It’s like connecting the dots,” he says, “a lot of dots.” Those connections, in turn, have yielded multiple drug targets that could be spun off into new commercial ventures.

Dr. Ramirez’s natural talent for gumshoe detective work has flourished under the tutelage of Dr. Bar-Sagi. During his initial interviews, Dr. Ramirez was impressed by Dr. Bar-Sagi’s emphasis on research fundamentals: methods, reproducibility, reporting, and verification.

She has since instilled in him the importance of presenting his data in ways that will make others care. He’s also gained an appreciation for attention to detail in planning and conducting experiments and for knowing which questions to ask first when testing a new hypothesis. “Being able to figure out the one or two questions to address, the direction you want to run with, that’s of big importance,” he says.

Mentors may have more experience and seniority, Dr. Bar-Sagi says, “but cross talk between a mentor and mentee provides an equal opportunity for both sides to learn from each other and enrich the experience.” During their frequent conversations, Dr. Ramirez takes the scientific ideas or suggestions Dr. Bar-Sagi discusses with him, and quickly comes up with a range of interesting new interpretations or hypotheses. “You throw one idea at him, and he will come up with a lot of new connections and possibilities,” Dr. Bar-Sagi says. “It’s a very special talent.”

Beyond the reward of seeing the fruits of his scientific detective work, Dr. Bar-Sagi says she’s appreciated helping Dr. Ramirez grow as an independent researcher and shape his career path. In particular, she’s benefited from the rich learning experience of helping her mentee gain the skills, resources and confidence necessary to try commercializing his ideas as an entrepreneur in biomedical research.

Eventually, Dr. Ramirez hopes to translate the research findings and collaborations he developed at NYU Langone to a spin-off biotechnology venture with the aid of NYU Langone’s Technology Ventures and Partnerships.

“The venture would be aimed at creating new therapeutic options for cancers with high unmet needs,” he says. In essence, he would turn his problem-solving skills toward coming up with yet another much-needed solution.

The Meaning of Mentorship

While managing her lab members as a team united by a common goal, Dr. Bar-Sagi has coaxed her mentees to gradually begin striking out on their own. “She’s been pushing me, in a good way, toward independence in being able to perform research, and she’s also encouraged and helped facilitate intra-NYU collaborations,” says mentee Dr. Ramirez. With her help, he has been able to network with other researchers within and beyond NYU Langone and see how he might translate his research in a clinical setting or pursue other career options. One highlight has been a collaboration, facilitated by Dr. Bar-Sagi and NYU Langone’s Technology Ventures and Partnerships, with a small biotech company. The researchers are now jointly investigating potential therapeutic targets linked to cancer pathways under investigation in the Bar-Sagi Lab. “As Dr. Bar-Sagi’s mentee, it sometimes feels like I’m a passenger allowed to sit in the cockpit with the pilot,” Dr. Ramirez says. “You’re able to see a 30,000-foot perspective of the inner workings of the research institute. That’s been unique and fascinating for me.”