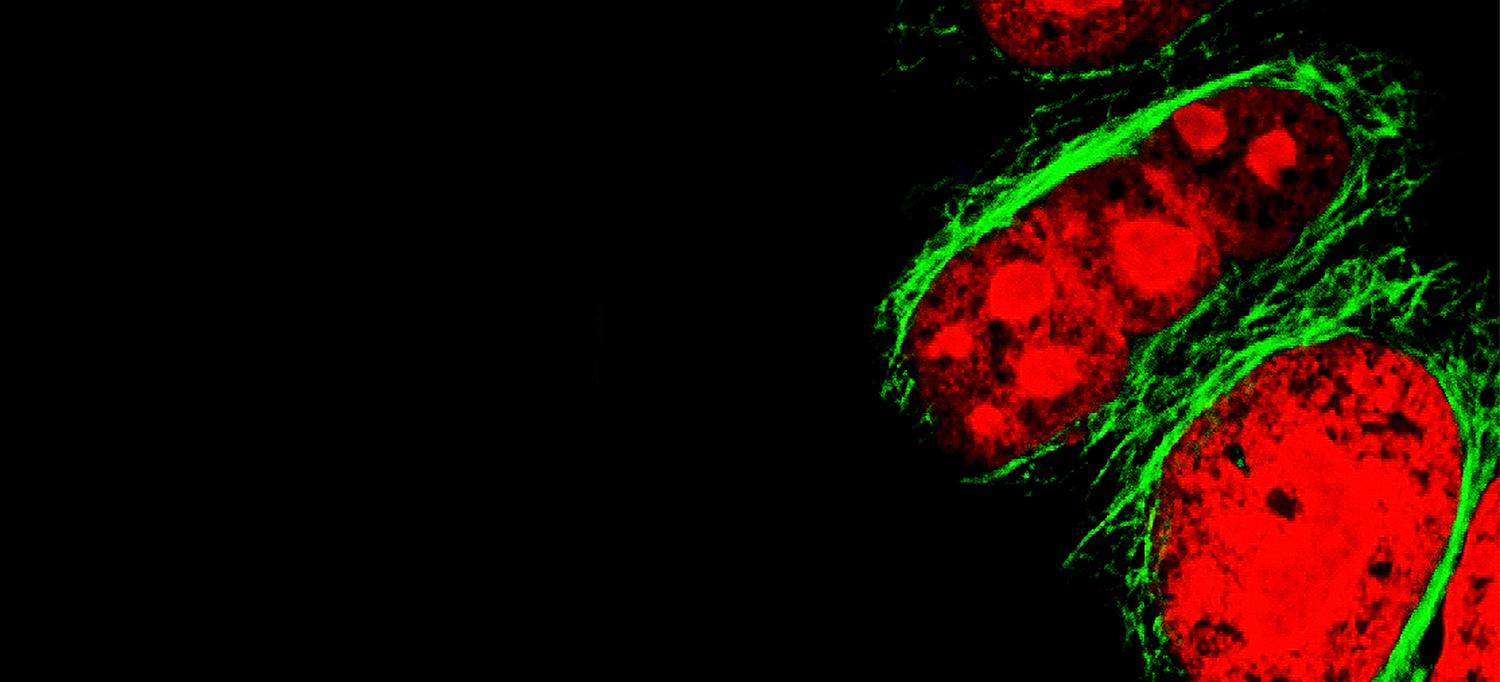

Photo: vshivkova/Getty

Past studies had disagreed on the identity of the cell in which high-grade ovarian cancer, the most lethal form of the disease, originates.

However, a new study finds that ovarian cancers may begin either in cells lining the outsides of ovaries or in cells on the surface of the adjacent fallopian tubes. Further, the cell-of-origin influences the growth rate of the resulting tumor, and the degree to which its responds to therapies, say the researchers.

These are the findings of a research effort led by investigators from Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health and published online November 26 in Nature Communications.

“Based on a better understanding of its origins, our study provides new insights into the biology and therapy of ovarian cancer,” says study first author Shuang Zhang, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at Perlmutter Cancer Center.

The research team used genetically engineered mice in which the same cancer-causing genetic changes (mutations) were found either in fallopian tube or ovarian surface cells, as well as in “organoids,” three-dimensional cell cultures grown from tissue taken from the mice.

The study authors found that both cell types gave rise to tumors, but the ones from the fallopian tube tended to spread more quickly and widely throughout the abdomen, while the ovarian surface–derived tumors gave rise to larger overall collections of tumor cells. Moreover, the fallopian tube–derived tumors were considerably more sensitive to cis-platinum, the major chemotherapy used for ovarian cancer.

Consistent with these findings, the researchers found that fallopian tube– and ovarian surface–derived tumors in mice expressed distinct sets of genes, many of which were expressed differently in the originating, normal cells. Cancer cells arise from normal cells in which disease-causing genetic changes have occurred.

By using these differentially expressed genes as a “signature” to compare human ovarian cancer cells with each other, and with normal cells, the team found that some human tumors are more fallopian tube–like, while others more ovarian-like. Also, while many of the same genetic alterations could be found in both types of tumor, some abnormalities appeared to be more common in either fallopian- or ovarian-derived tumors.

“Our results suggest that high-grade cancer can originate in more than one cell type, and that the original cell type can significantly influence tumor behavior and therapy response,” says senior study author Benjamin G. Neel, MD, PhD, director of Perlmutter Cancer Center. In the future, he says, physicians may need to consider the cell-of-origin, along with the specific genetic changes in the tumor, to optimize and personalize therapy.

In addition to Dr. Zhang and Dr. Neel, co-authors of the study from Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone were Igor Dolgalev, Tao Zhang, Hao Ran, and Douglas A. Levine. Funding for the study came from Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-191992, National Cancer Institute Center Core Grant P30 CA016087, U.S. Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program W81XWH-15-1-0429, and support from the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance.

Media Inquiries

Greg Williams

Phone: 212-404-3500

gregory.williams@nyulangone.org