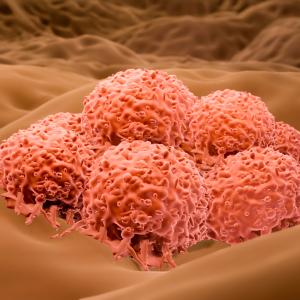

Melanoma cells growing in culture. NYU Langone researchers seek to predict which ones will metastasize.

Photo: Karsten Moran

How does an isolated tumor that starts in melanocytes, the cells that produce skin pigment, spread so aggressively to other parts of the body? This fundamental question guides Eva Hernando, PhD, as she investigates the molecular basis of metastatic melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer.

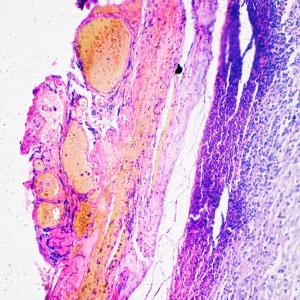

The search for answers took a critical turn when Dr. Hernando-Monge, associate professor of pathology and a member of the Helen L. and Martin S. Kimmel Center for Stem Cell Biology joined the Interdisciplinary Melanoma Cooperative Group (IMCG) at NYU Langone’s Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center in 2006. The prospect of collaborating with researchers across a broad range of disciplines was a big draw for Dr. Hernando. Although cancer research often begins by studying cancer cells in tissue culture or in mouse models and then progresses to human tissue samples, Dr. Hernando starts with patient specimens. She and her colleagues use the IMCG’s bank of 17,000 human tissue specimens to ask the questions most relevant to patients and then they design experiments to obtain answers.

Collaborative Spirit Supports Innovation

“We never work in isolation,” says Dr. Hernando. “We focus on different aspects of melanoma biology but with the main goal of understanding what makes tumor cells spread and how we can use that information to identify and treat patients who are at highest risk for aggressive melanoma.”

That collaborative spirit has resulted in a series of discoveries centered on rogue cells that fail to differentiate into mature melanocytes. In an article published in 2013, Dr. Hernando and her team described how melanoma cells overexpress BRD4, a protein known to fuel tumor growth. Inhibiting BRD4, the researchers found, inhibited melanoma growth. Last year, the team found that the same protein helps melanoma cells continue to proliferate. In yet another promising discovery, the team found that more aggressive melanomas lose a specific group of microRNAs, a class of molecules that modulate protein levels.

“The same microRNAs that regulate aggressive features of melanoma cells can tell us which patients are at higher risk of developing more metastatic tumors,” says Dr. Hernando.

Discovery Could Lead to New Diagnostics

Better diagnostics for melanoma are urgently needed because current methods do not reliably predict which melanoma cells will metastasize. Once melanoma has spread to other parts of the body, it is very difficult to treat: if melanoma is caught early, the survival rate is higher than 92 percent, but when diagnosed at its most advanced stages, life expectancy can be less than a year. A prognostic assay based on an miRNA expression signature, combined with staging criteria, could improve patient prognoses and aid clinical management of patients.

Partnership Benefits Melanoma Research

As part of an exciting new initiative that has taken NYU Langone research to a new continent, Dr. Hernando and colleagues are now collaborating with the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in the fight against cancer. The partnership, funded by a $9 million gift from philanthropists and NYU Langone trustees Laura and Isaac Perlmutter, bridges two world-class research enterprises and is a milestone in NYU Langone’s commitment to international collaboration.