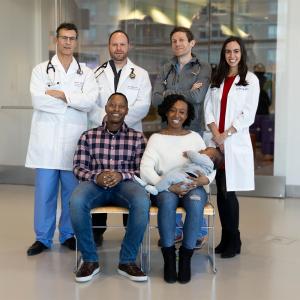

Experts at NYU Langone’s Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, including Dr. Dan G. Halpern, pinpoint the cause of Tyler Reynolds’s chest pain and offer an innovative solution.

Photo: NYU Langone Staff

Rowing, running, and biking are just some of the many physical activities that Tyler Reynolds pursued as a child. To watch him as he conquered one sport after another, you’d never have known he was born with a congenital heart defect that required surgical repair just days after birth.

The procedure, performed 25 years ago at NYU Langone, corrected a condition called dextro-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA), in which the two major arteries that carry blood away from the heart—the aorta and the pulmonary artery—are switched and connected to the wrong heart chambers.

Throughout his life, Reynolds strove to live like someone with a normal heart. In college, he continued to row and wanted to compete in triathlons. However, a serious obstacle stood in his way: Long physical exertion frequently resulted in severe chest pain and shortness of breath. “It felt like I was having a heart attack,” he says.

These symptoms started his junior year of high school. But heart scans and stress tests from repeated trips to the emergency department always came back normal. Seeing nothing alarming in the standard imaging, doctors surmised the cause was inflammation of the cartilage that connects the breastbone to the ribs. “I thought this pain was typical during a workout and something I just needed to push through,” says Reynolds.

VIDEO: Tyler Reynolds and his NYU Langone Heart care team discuss his condition and successful treatment plan.

When he was in his early 20s, Reynolds began seeing a general cardiologist who suspected there was more going on than just inflammation. He recommended a full evaluation with the team at the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, part of NYU Langone Heart. They are experts at identifying the causes of red-flag symptoms in adults born with heart disease. In addition to chest pain and shortness of breath, signs of concern are irregular heartbeat; blue fingernails, lips, and skin; intense fatigue after physical activity; and edema, or tissue swelling.

Reynolds met with Dan G. Halpern, MD, medical director for the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program, and Jodi L. Feinberg, NP, nurse practitioner program manager. They made a lifesaving discovery.

“A standard stress test has limitations in well-conditioned young people like Tyler,” says Dr. Halpern. “It may miss more subtle heart changes or those that appear with more exertion.” In addition, the results of the test’s electrocardiogram portion can sometimes be misleading in people who have had heart surgery.

Moreover, Reynolds’s complaint of chest pain during physical effort that disappears during rest was indicative of angina, in which not enough blood flows through the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart. “This is why we decided to run further tests,” says Dr. Halpern.

A catheterization and CT coronary angiogram, which uses special dye to visualize the anatomy of the arteries and identify any blockages, revealed Reynolds had just a single coronary artery, which had split into a dominant right coronary artery and a left main coronary artery. Normally, there are two separate coronary arteries with several branches. Added to that, Reynolds’s left main coronary artery was severely narrowed and more than 75 percent blocked by scar tissue.

“As an adult congenital cardiologist, I know that Tyler had state-of-the-art heart surgery when he was a baby, and that people who have this procedure typically do very well,” says Dr. Halpern. “But I also know what complications can come up decades after surgically manipulating a baby’s coronary arteries. A single coronary artery is one of them.”

The extremely narrow single coronary artery presented treatment challenges, and the care team wanted to ensure that Reynolds would be able to maintain his active lifestyle. The more traditional options for repair did not make sense based on Reynolds’s heart anatomy. They also had not been proven to be long-lasting.

Instead, congenital cardiothoracic surgeons Ralph S. Mosca, MD, and T.K. Susheel Kumar, MD, decided on an innovative approach to repair Reynolds’s heart: a coronary arterioplasty to alleviate the artery narrowing. “The surgery we performed was the more complicated option, but it also has the potential to last a lifetime,” Dr. Kumar says. The surgery was performed at NYU Langone, which is ranked among the top 5 hospitals in the country for cardiology and heart surgery by U.S. News & World Report.

The coronary arterioplasty first required an incision across the narrowed artery. Next, surgeons grafted a patch into the vessel. This patch was created from a segment of femoral artery that came from the thigh of a deceased donor. “Using this graft was a unique approach and gave us a beautiful result of a widened, normal looking artery,” says Dr. Kumar.

After a few days recovering in the hospital, Reynolds returned home and was able to start training again. He continues to have routine checkups with the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program care team. “We offer ongoing monitoring to ensure Tyler doesn’t have any structural or heart rhythm problems,” says Dr. Halpern.

About three months after surgery, Reynolds ran a 10K “just for fun.” He is now back to rowing, and rides his bike to work every day. He runs races and finishes in the middle of the pack, with the goal of being in the top 10 percent. “I’m so grateful to my care team,” says Reynolds. “I’m able to do these high-endurance physical activities again without paying the price physically.”

Read and watch more from NY1 and News 12 Brooklyn.