When a Bold Postdoc Wanted to Explore an Uncertain Avenue of Research, His Mentor Relied on Her Own Instincts, Encouraging Him to Pursue His Curiosity

Eva Hernando-Monge, PhD, associate professor and vice chair for science in the Department of Pathology and associate director for basic research at Perlmutter Cancer Center, and postdoctoral fellow Doug Hanniford, PhD

Photo: Tony Luong

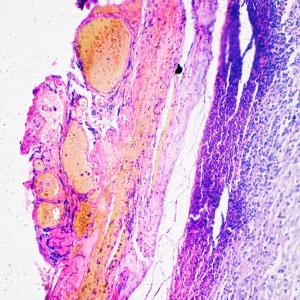

In 2006, at age 28, Doug Hanniford, PhD, was itching to become a better scientist and left a comfortable job at a Cleveland biotechnology company to enroll as a PhD candidate in NYU Langone Health’s Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences. He flourished in the lab of Eva M. Hernando-Monge, PhD, associate professor of pathology, where he uncovered new details about how small RNA molecules called microRNAs regulate the progression of melanoma.

Roughly 87,000 Americans are diagnosed with this dangerous skin cancer every year, and scientists are trying to determine the mechanisms behind its deadly metastatic spread, in which cancer cells break away from the primary tumor and disperse throughout the body.

For his postdoctoral research, however, Dr. Hanniford wanted to go in a new and uncertain direction. Most RNA molecules resemble tiny braided ribbons.

But research had suggested that some microRNAs might interact with a more unusual type of RNA whose ends stick together to form a circle.

Although rare examples of such circular RNAs had been described in bacteria and some animals, advanced sequencing methods had only recently revealed their presence in humans, raising more questions than answers: Are they just a biological accident? Do they even have a function? Dr. Hanniford, for his part, suspected that a particular circular RNA known to interact with the microRNAs might play an influential role in melanoma’s devastating spread.

Dr. Hernando-Monge admits that she was initially skeptical of the idea, but she encouraged Dr. Hanniford to follow his curiosity. A member of her lab since its inception in 2006, he had earned a reputation for meticulous, dogged research. “He’s a stickler for details,” Dr. Hernando-Monge says, noting that he has coauthored more than 15 articles. “He doesn’t rush or compromise the quality of his studies.”

For Dr. Hanniford, any fear of failure was offset by Dr. Hernando-Monge’s unwavering support and by the prospect of discovering something completely new to the world. He loves the creativity of science and the possibility that discoveries can open up unexpected avenues of research.

His research has done just that, bringing into view a unique molecular mechanism in the field of cancer pathology.

His findings suggest that the loss of a certain circular RNA in human melanoma cells enhances melanoma’s metastatic potential. In particular, he’s shown that melanoma recruits a protein complex to silence and evade this particular bit of circular RNA. That silencing, in turn, may enhance the function of another tumor-promoting protein. His discoveries, Dr. Hernando-Monge says, point toward novel therapeutic interventions that could either boost the circular RNA molecule’s normal anticancer activity or replicate its ability to keep cancer from spreading.

“It’s a very exciting story,” Dr. Hernando-Monge says. “I really have to thank him for bringing the lab into an area where, on my own, I probably would not have gone.” The ability to take risks and embrace new concepts and techniques, she says, is the hallmark of a great investigator.

The Meaning of Mentorship

For Dr. Hernando-Monge, one of the highlights of mentorship is watching trainees grow into mentors themselves. “I love the point when the student is teaching me,” Dr. Hernando-Monge says. She empowers her students to take responsibility for their work early on and encourages them to engage with other scientists through discussions, presentations, and meetings. This approach, she believes, instills the confidence young scientists need to set out on their own and chart new scientific territory. “Without risk,” she says, “there are no new discoveries.”