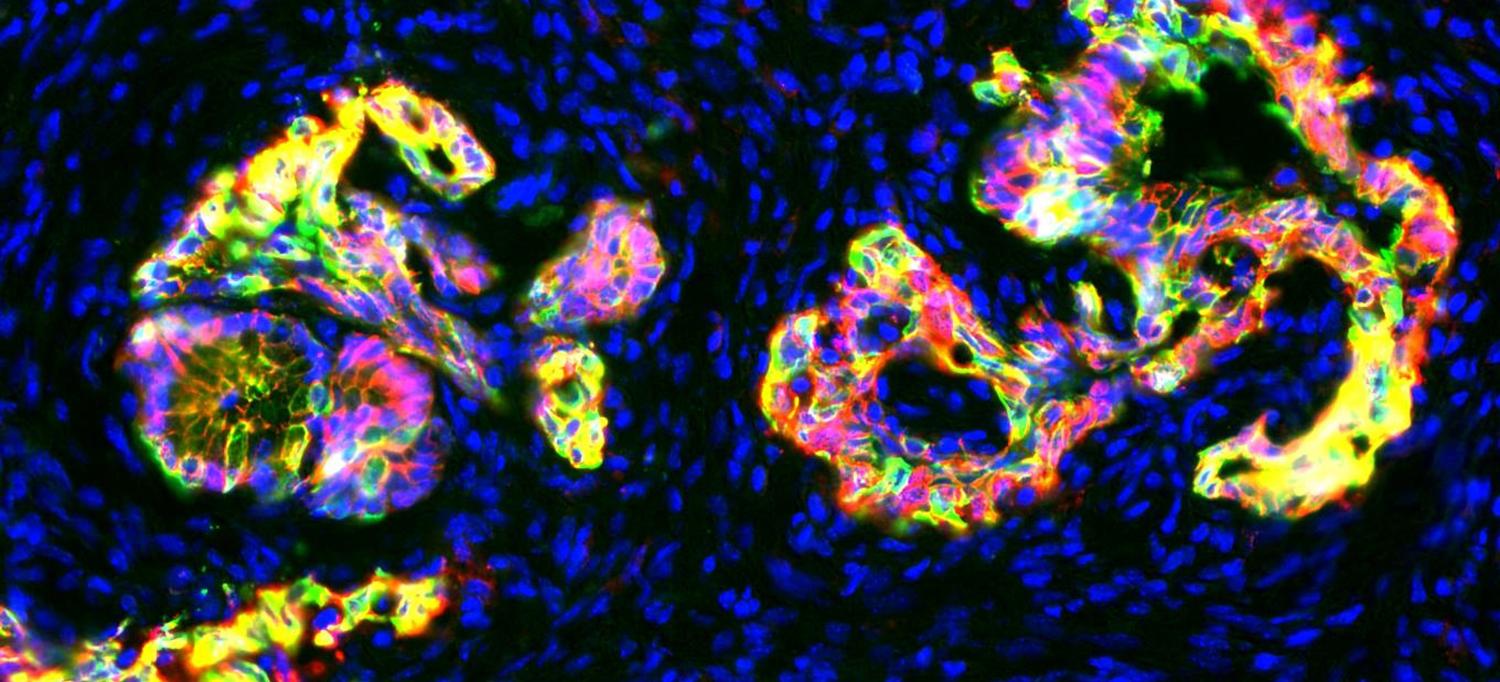

Precancerous pancreatic tissue in mice.

Photo: Nathan Krah, University of Utah

In recent years, researchers have hoped to combat pancreatic cancer by developing drugs that interfere with tumor cells’ source of fuel. But a study led by researchers at NYU Langone and other institutions has found that when their glucose fuel supply runs low, pancreatic cancer cells signal to nearby support cells for help supplying them with nourishment. The study, published in the journal Nature, was based on research conducted in collaboration with teams from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Harvard University and the University of Michigan Medical School.

Intrigued by the fact that pancreatic cancer cells keep growing even when they have very little oxygen and blood sugar, or glucose, normally supplied by the bloodstream, Alec Kimmelman, MD, PhD, wanted to find out how that happened. Dr. Kimmelman, chair of the Department of Radiation Oncology, led a team of investigators that discovered that pancreatic tumor cells communicate with nearby stellate cells—healthy cells that secrete substances providing structural support. By emitting an unknown chemical, hungry tumor cells signal the stellate cells to break down their own components into various building blocks, including the amino acid alanine. In the presence of alanine, the tumor cells’ mitochondria, or cellular motors, revved up by 20 to 40 percent, indicating that the alanine was being used as fuel source in place of glucose.

When their glucose supply is limited, cancer cells can scrounge for enough nourishment to take steps that enable them to multiply, like building new strands of DNA and RNA. “In nutrient-poor conditions, alanine is providing meta-bolic efficiency,” explains Dr. Kimmelman. “These tumor cells have an unbelievable capacity to scavenge and adapt.” When they tested this theory in mice, deactivating a gene that allows the breakdown in stellate cells, tumor growth slowed significantly compared to those grown with normal stellate cells, since they no longer had access to the secreted alanine.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal forms of cancer, with an overall five-year survival rate of just 7 percent. While current therapies have shown some efficacy, there is a lot of room for improvement. Dr. Kimmelman and his colleagues think it may be possible to strike back at tumor cells by limiting their scavenging abilities. “We are continuing to explore how pancreatic cancers alter their metabolism to provide essential building blocks they need,” he says. His team hopes that decoding tumor cells’ survival strategies will pave the way for future drugs that starve out pancreatic tumors.