First Successful Attachment of Nonhuman Kidney Signals Fresh Hope for Patients Awaiting a Transplant

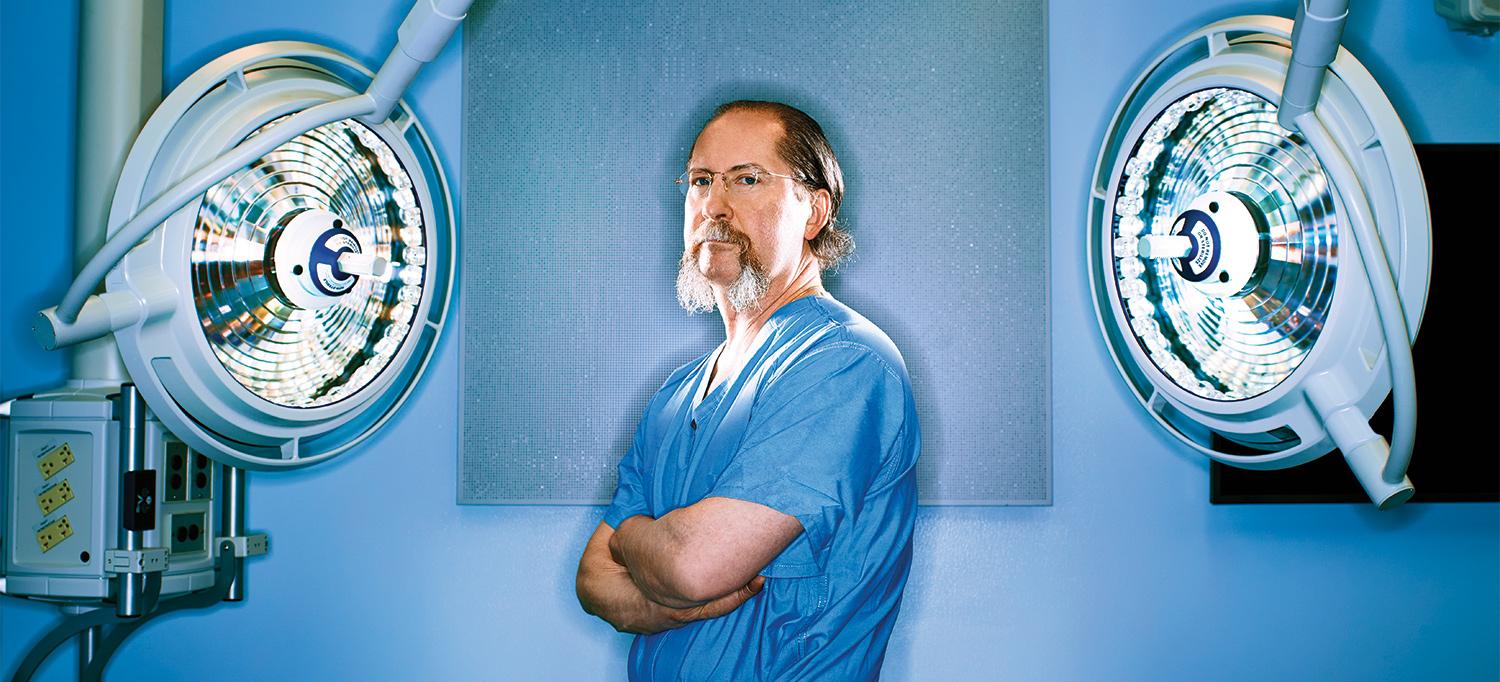

Dr. Robert Montgomery, who received a heart transplant himself in 2018, believes xenotransplantation may one day end the shortage of donor organs, potentially saving the lives of countless thousands. “I predict that a decade from now, we’ll be broadly transplanting kidneys, hearts, lungs, and livers from pigs into living humans,” he says.

Photo: Brad Trent

The concept of transplanting animal organs, tissues, or cells into humans has a long and fitful history. In 1667, King Louis XIV’s personal physician tapped the veins of farm animals to perform blood transfusions. The practice was quickly banned when two patients died.

Fast forward three centuries to 1963, when Dr. Keith Reemtsma, a pioneer of organ transplantation at Tulane University, transplanted kidneys from 13 chimpanzees into humans. All the recipients died from infections, but one 23-year-old woman survived for 9 months. Her case was a watershed moment for cross-species transplantation, or xenotransplantation, and inspired a flurry of new research.

Today, after nearly six decades, that scientific investment is paying major dividends with a rush of remarkable clinical advances. On September 25, 2021, NYU Langone Health completed the first successful transplant of a nonhuman kidney to a deceased donor whose circulation was sustained through life support. The pig kidney, genetically engineered for humans and attached to the blood vessels in the upper leg of the decedent donor, functioned perfectly throughout the 54-hour study.

Days later, surgeons at the University of Alabama at Birmingham transplanted two pig kidneys into the abdomen of a deceased donor for three days. Just three months later, surgeons from the University of Maryland achieved another critical milestone by implanting an engineered pig heart into a living patient. The 57-year-old man had terminal heart disease and failed to be listed for a human heart because of a history of poor compliance with medical care. The patient, who remained hospitalized, died two months later. At press time, it was unclear whether organ rejection contributed to his death. Yet, the mere fact that the pig heart functioned well for more than a month represents a milestone in medical science.

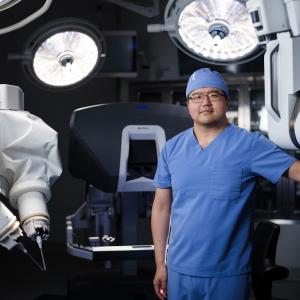

For Robert Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, who led the xenotransplant surgical team, the rapid progress represents a major turning point for the field of transplantation—one that could potentially save the lives of many of the 6,000 patients who die annually waiting for a donor organ. “As a heart transplant recipient myself due to a genetic disorder, I am thrilled by the news of a successful xenotransplant of the heart and the hope it gives to my family and other patients who will eventually be saved by this breakthrough,” says Dr. Montgomery, the H. Leon Pachter, MD, Professor of Surgery and chair of the Department of Surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

“What was profound about our findings was that the pig kidney functioned just like a human kidney does,” says Robert Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

Xenotransplants, more than any other medical innovation, hold the power to solve the critical shortage of available donor organs, most notably among the 90,000 people on the kidney waiting list. Nearly half of them will become too ill or die before receiving a donor organ. And that’s not counting the 500,000-plus Americans with end-stage kidney disease who depend on dialysis, a lifesaving yet demanding regimen in which a machine removes toxins and excess fluid and salt from the blood three times a week. Many of these patients would qualify for a transplant if the supply of available organs could meet the demand. “Individuals who receive a kidney transplant live twice as long on average as those on dialysis, with a better, more independent quality of life,” Dr. Montgomery adds.

NYU Langone’s landmark experiment aimed to test whether a genetically engineered pig organ would function properly in a human body, and it did. Significantly, there were no signs of rejection, a validation of the genetic engineering used to eliminate the sugar molecule in the pig kidney that has spurred organ rejection in previous attempts at performing a xenotransplant into humans. A second xenotransplant, performed two months later under the same conditions at NYU Langone, had identical, highly encouraging results. “What was profound about our findings was that the pig kidney functioned just like a human kidney transplant does,” says Dr. Montgomery. As with all trials in humans, the study, submitted for peer review, was approved by an NYU Langone research ethics oversight board.

Dr. Montgomery’s latest success builds on a long resume of transplant innovations, including pioneering work in the laparoscopic procurement of donor kidneys, which eases the recovery process for donors; the expanded use of organs containing the hepatitis C virus for transplant; and domino paired donation, a method of swapping live donor kidneys to compatible patients that is responsible for nearly 1,000 transplants each year in the United States.

Building on its recent successes, NYU Langone is forging ahead on multiple fronts. Dr. Montgomery plans to conduct another kidney transplant study among deceased donors that will examine what happens between two and four weeks following transplant, when potentially severe rejection problems could develop. “This study will optimize the information we can get before embarking on a phase 1 trial in living humans,” says Dr. Montgomery.