The Institute for Excellence in Health Equity Aims to Eliminate Racial Disparities Across NYU Langone Health. Its First Mission: To Reform Algorithms with Built-In Biases.

As part of one initiative designed to combat racial disparities in healthcare, Dr. Joseph E. Ravenell leverages community health workers to screen Black men for hypertension in barbershops.

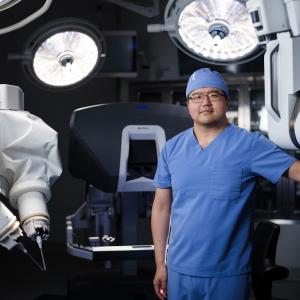

Photo: Joshua Bright

Medicine is the science of risk calculation. It makes sense, then, that physicians routinely rely on data-driven, evidence-based formulas and calculations to help discern risks and guide treatment protocols for their patients. Nearly every specialty of medicine uses clinical-decision tools, and more than 90 percent of hospitals have integrated medical algorithms into electronic health records in an effort to improve outcomes. But what happens when those tools propagate faulty assumptions and bad data? According to a landmark paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2020, the results can be devastating, especially for Black and Hispanic patients.

At least 15 clinical algorithms in use today—many of them endorsed by leading medical associations—embed race into the equation, notes Olugbenga G. Ogedegbe, MD, MPH, founder and inaugural director of NYU Langone’s Institute for Excellence in Health Equity. “Clinical calculators are used as a proxy for the gold-standard treatment of patients,” says Dr. Ogedegbe, the Dr. Adolph and Margaret Berger Professor of Medicine and Population Health. But when the calculations adjust outcomes based on race, he notes, the formulas can result in different treatments and procedures for Black patients than White patients, often resulting in worse outcomes. “Race should not matter in a patient’s treatment,” adds Dr. Ogedegbe. “Care should be color-blind.”

One such calculator already corrected at NYU Langone assesses kidney function. The formula assigns Black patients a higher filtration-rate score, a measure of the kidney’s ability to rid the body of a waste product called creatinine. “The bad assumption baked into this tool is that Black patients have more muscle mass and therefore higher levels of creatinine,” says Dr. Ogedegbe. “This is just false.” For Black patients with early-stage kidney disease, the adjustment could mean a missed opportunity to receive specialty care, and for those with end-stage kidney failure, the score correction could render them ineligible for the kidney transplant wait list (see “Eliminating Bias from Clinical Calculators” below).

“Race should not matter in a patient’s treatment,” says Olugbenga G. Ogedegbe, MD, MPH, founder and inaugural director of NYU Langone’s Institute for Excellence in Health Equity. “Care should be color-blind.”

“Race is a social construct, and yet it has been used as a substitute for genetic and biological factors for decades,” says Kathie-Ann Joseph, MD, MPH, professor of surgery and population health and vice chair for diversity and health equity in surgery and at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute. “These calculations assume inherent differences instead of digging deeper into the social determinants that explain why Black people have worse outcomes.”

The mission of the Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, founded last year, is to analyze and address the causes of health inequities and, ultimately, level the playing field in clinical care, scientific research, and medical education. Dr. Ogedegbe has spent the last 30 years addressing racial disparities in medicine. Reviewing race-based algorithms is one part of the institute’s larger mandate to ensure health equity is applied to patient experience, data collection through NYU Langone’s electronic health record system, and the mentoring of residents and students at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “We have to reimagine healthcare completely,” says Dr. Ogedegbe. “We want to become the leader within this space.”

In some cases, removing racial bias is straightforward once it is revealed, as in the case of a clinical decision tool that had assessed Black and Hispanic women as being 20 percent less likely than White women to have a successful vaginal birth after a previous cesarean delivery. That adjustment has been eliminated from the model. In other cases, though, NYU Langone clinicians may need to find—or create—a replacement calculator. “As doctors, we should be asking why race is a part of these guidelines or of our care,” Ilseung Cho, MD, NYU Langone’s chief quality officer, who is leading the effort to review clinical calculators for implicit bias and remove or correct them. “We have an ethical and moral responsibility to close any gaps.” He notes that simply pointing out race-based corrections to doctors is often enough to move the needle. “Everybody here aspires to provide equitable care,” Dr. Cho says.