Zebrafish learn to balance by darting forward when they feel wobbly, a principle that may also apply to humans, according to a study led by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center.

The fish make good models to understand human balance because they use similar brain circuits, say the study authors. The researchers hope their work will one day help therapists to better treat balance problems that affect one in three aging Americans, and for whom falls are a leading cause of death.

Published online January 19 in Current Biology, the new study found that early improvements in a zebrafish’s balance emerge from its growing ability to execute quick swims in response to the perception of instability. Over time young fish learn to make corrective movements when unstable and become better at remaining stable.

“By untangling the forces used by the fish while swimming, and during the pauses between these corrective movements, we may have uncovered a foundational balance mechanism—the mental command to start moving when unstable,” says lead study investigator David Schoppik, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Neuroscience and Physiology at NYU Langone.

The behavioral tendencies revealed in the new study confirm past work that found balance to depend on networks of connections between brain cells, called neural circuits, that link sensory organs in the balance, or vestibular, system to muscles that make corrective movements.

Along with zebrafish, many animals have heavy heads, which require constant corrections to keep them from pitching forward. Humans too literally fall forward as they walk and then compensate with bursts of forward leg motion, but unlike zebrafish become less top heavy as they develop, says Schoppik, also an assistant professor in the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

“We plan next to test whether or not toddlers, like the fish in our study, are more likely to move when they feel unstable,” says study author David Ehrlich, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Schoppik’s lab who led many of the experiments. “Further, do adults take smaller, quicker steps on icy sidewalks or in the dark, especially as our balance system deteriorates with age?”

56,000 Swims

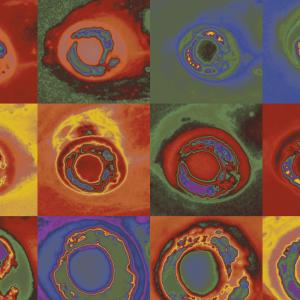

In the current study, researchers recorded video of 56,682 swims by zebrafish larvae, measuring the timing of each quick swim and the effectiveness of efforts to remain stable with age. The videos confirmed that the fish swim in “bouts,” and that they are much more likely at 21 days of age than at 4 days to start a corrective swim bout when falling forward at high speed.

Based on the videos, the team was then able to create a computer simulation of the swimming fish based on an elegant series of equations. In a sign that they had arrived at a strong understanding of balance, the simulations behaved very much like the real fish, say the authors.

Researchers next removed elements from the simulation to further clarify the role of each in balance. Removing “pitch correction,” the tendency of fish to swim up if they had swam downward in the previous bout, or vice versa, left fish unable to correct when tipped over. Instead, they spent their simulated lives with their heads pointed down toward the tank’s bottom. When the team removed the relationship between angular velocity, or how fast the fish is rotating, and the fish’s reactive bout kinematics (the force of countering swims), the simulated fish pitched endlessly forward, rolling head over heels.

VIDEO: NYU Langone researchers describe how animal brains make the calculations needed to achieve balance.

Moving forward, the team will seek to measure the changes in brain activity that occurs as zebrafish learn to balance. In the future, they hope to partner with the clinicians at the Vestibular Rehabilitation Program at NYU Langone’s Rusk Rehabilitation to advance rehabilitation medicine.

“Many patients that have suffered a stroke, or have had brain cancer or trauma, struggle with balance problems or dizziness,” says Tara Denham, PT, manager of Rusk Rehabilitation’s Vestibular Rehabilitation Program. “A better understanding of how the brain perceives balance may help us to fine-tune exercise programs that restore lost function or shorten recovery times.”

The study was supported by a grant (5R00DC012775) from the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Media Inquiries

Greg Williams

Phone: 212-404-3533

gregory.williams@nyumc.org