A key cellular signal provides a vital balance between the body’s ability to destroy invading microbes and its need to prevent autoimmune disease, in which immune cells attack the body’s own tissues. That is the finding of a study led by researchers from NYU Langone Medical Center and published May 31 in the journal Immunity.

Specifically, the study in mice and humans found that a certain type of calcium-based signal regulated the production of two immune cell types: T follicular helper cells that drive the body’s massive reaction to invading organisms, and T follicular regulatory cells, which ramp that reaction down as soon as infection is finished. Immune cells create chemicals that kill microbes and cause inflammation, which can destroy tissues at too-high levels.

“We found that calcium signals play a vital role in keeping the immune system finely balanced, ramping responses up and down at the appropriate time,” says senior author Stefan Feske, MD, an associate professor of pathology at NYU Langone. “Future applications of our findings may include fine-tuning calcium signals to enhance immune responses to influenza vaccines for the elderly, or the design of new options for people with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

VIDEO: Dr. Stefan Feske explains how a newfound mechanism ramps the immune system up and down and its implications for vaccine design.

“Our results also are timely because the field is currently exploring whether a drug class called CRAC calcium channel inhibitors can be useful in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases,” Feske adds. “Researchers will need to weigh carefully the potential benefits against the possibility that these drugs interfere with our ability to fight infections.”

Based on Charge

The study results revolve around the fact that every human cell pumps charged particles like calcium in and out through channels, building up imbalances along cell membranes. Upon receiving the right signal, cells open the channels, enabling particles to rush back under electrical force, with the charge flow acting like an electric switch that kicks on cell processes.

In the current study, the research team found that one type of calcium influx, called store-operated calcium entry (SOCE), ramps immune responses up and down by controlling the “decision” by immune cells to become either T follicular helper, or T follicular regulatory, cells. SOCE governs follicular T cell lineage by interacting with transcription factors like NFAT, IRF4, and BATF, proteins that attach to the DNA chain and turn on sets of genes, say the authors.

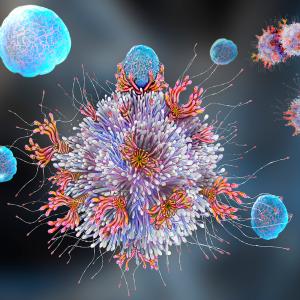

The research team has also shown for the first time how this type of calcium entry, through its regulation of follicular T cells, governs the formation and breakdown of germinal centers. Within such centers, the workhorses of the immune system—T and B cells—partner to churn out vast numbers of slightly different antibodies, immune proteins that glom onto and remove from the system the invading microbe at hand.

Though vital to effective immune responses, T helper follicular cells can also inappropriately help B cells produce “auto” antibodies that recognize the body’s own cells as foreign and attack them. This is the case in the kidneys of people with lupus and the joints of people with rheumatoid arthritis. The current study found that SOCE balances the immune system, producing antibodies and inhibiting auto-antibodies as needed.

Going into the study, it was well established that calcium entry into T cells happens through channels called calcium release-activated channels (CRAC), and that such signaling was regulated by proteins called STIM1 and STIM2. The new study found that mice genetically engineered to lack genes for these proteins are much less able to mount antibody responses to viral infection. Without normal calcium signaling, the mice could not form normal germinal centers, and died prematurely. At the same time, aging mice were found to be more susceptible to developing autoimmune disease because of an increasing imbalance between T follicular helper and regulatory cells.

“The function of SOCE via CRAC channels is two-fold: it regulates the transcriptional programming of T regulatory cells to prevent auto-antibodies from targeting the body’s own proteins in between infections,” says first author Martin Vaeth, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Feske’s laboratory. “SOCE is also essential for the maturation of T follicular helper cells and production of antibodies in response to invasion by viruses.”

Along with the mouse results, the study team looked at the experience of humans with a rare disease called CRAC-channelopathy, which affects only 30 people worldwide and is caused by genetic mutations in the CRAC channel. These patients are extremely susceptible to infections early in life and to autoimmunity as well. Among the goals of the research effort is to help these people, along with all those who suffer from more common, immune-related diseases.

Along with Feske and Vaeth, authors of the study were Miriam Eckstein, Patrick Shaw, Lina Kozhaya, Jun Yang, Robert Clancy, and Derya Unutmaz at NYU Langone, and Friederike Berberich-Siebelt at the University of Wurzberg in Germany.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone.

Media Inquiries

Greg Williams

Phone: 212-404-3533

gregory.williams@nyumc.org